To the Hard Members of the Truthy SF Club

“Nothing is as soft as water, yet who can withstand the raging flood?” — Lao Ma in Xena (The Debt I)

Being a research scientist as well as a writer, reader and reviewer of popular science and speculative fiction, I’ve frequently bumped up against the fraught question of what constitutes “hard” SF. It appears regularly on online discussions, often coupled with lamentations over the “softening” of the genre that conflate the upper and lower heads.

Being a research scientist as well as a writer, reader and reviewer of popular science and speculative fiction, I’ve frequently bumped up against the fraught question of what constitutes “hard” SF. It appears regularly on online discussions, often coupled with lamentations over the “softening” of the genre that conflate the upper and lower heads.

In an earlier round, I discussed why I deem it vital that speculative fiction writers are at least familiar with the questing scientific mindset and with basic scientific principles (you cannot have effortless, instant shapeshifting… you cannot have cracks in black hole event horizons… you cannot transmute elements by drawing pentagrams on your basement floor…), if not with a modicum of knowledge in the domains they explore.

So before I opine further, I’ll give you the punchline first: hard SF is mostly sciency and its relationship to science is that of truthiness to truth. Remember this phrase, grasshoppahs, because it may surface in a textbook at some point.

For those who will undoubtedly hasten to assure me that they never pollute their brain watching Stephen Colbert, truthiness is “a ‘truth’ that a person claims to know intuitively ‘from the gut’ without regard to evidence, logic, intellectual examination, or facts.” Likewise, scienciness aspires to the mantle of “real” science but in fact is often not even grounded extrapolation. As Colbert further elaborated, “Facts matter not at all. Perception is everything.” And therein lies the tale of the two broad categories of what gets called “hard” SF.

Traditionally, “hard” SF is taken to mean that the story tries to violate known scientific facts as little as possible, once the central premise (usually counter to scientific facts) has been chosen. This is how authors get away with FTL travel and werewolves. The definition sounds obvious but it has two corollaries that many SF authors forget to the serious detriment of their work.

The first is that the worldbuilding must be internally consistent within each secondary universe. If you envision a planet circling a double sun system, you must work out its orbit and how the orbit affects the planet’s geology and hence its ecosystems. If you show a life form with five sexes, you must present a coherent picture of their biological and social interactions. Too, randomness and arbitrary outcomes (often the case with sloppily constructed worlds and lazy plot-resolution devices) are not only boring, but also anxiety-inducing: human brains seek patterns automatically and lack of persuasive explanations makes them go literally into loops.

The second is that verisimilitude needs to be roughly even across the board. I’ve read too many SF stories that trumpet themselves as “hard” because they get the details of planetary orbits right while their geology or biology would make a child laugh – or an adult weep. True, we tend to notice errors in the domains we know: writing workshop instructors routinely intone that authors must mind their p’s and q’s with readers familiar with boats, horses and guns. Thus we get long expositions about stirrups and spinnakers while rudimentary evolution gets mangled faster than bacteria can mutate. Of course, renaissance knowledge is de facto impossible in today’s world. However, it’s equally true that never has surface-deep research been as easy to accomplish (or fake) as now.

As I said elsewhere, the physicists and computer scientists who write SF need to absorb the fact that their disciplines don’t confer automatic knowledge and authority in the rest of the sciences, to say nothing of innate understanding and/or writing technique. Unless they take this to heart, their stories will read as variants of “Once the rockets go up, who cares on what they come down?” (to paraphrase Tom Lehrer). This mindset leads to cognitive dissonance contortions: Larry Niven’s work is routinely called “hard” SF, even though the science in it – including the vaunted physics – is gobbledygook, whereas Joan Slonczewski’s work is deemed “soft” SF, even though it’s solidly based on recognized tenets of molecular and cellular biology. And in the real world, this mindset has essentially doomed crewed planetary missions (of which a bit more anon).

As I said elsewhere, the physicists and computer scientists who write SF need to absorb the fact that their disciplines don’t confer automatic knowledge and authority in the rest of the sciences, to say nothing of innate understanding and/or writing technique. Unless they take this to heart, their stories will read as variants of “Once the rockets go up, who cares on what they come down?” (to paraphrase Tom Lehrer). This mindset leads to cognitive dissonance contortions: Larry Niven’s work is routinely called “hard” SF, even though the science in it – including the vaunted physics – is gobbledygook, whereas Joan Slonczewski’s work is deemed “soft” SF, even though it’s solidly based on recognized tenets of molecular and cellular biology. And in the real world, this mindset has essentially doomed crewed planetary missions (of which a bit more anon).

Which brings us to the second definition of “hard” SF: style. Many “hard” SF wannabe-practitioners, knowing they don’t have the science chops or unwilling to work at it, use jargon and faux-manliness instead. It’s really the technique of a stage magician: by flinging mind-numbing terms and boulder-sized infodumps, they hope to distract their readers from the fact that they didn’t much bother with worldbuilding, characters – sometimes, not even plots.

Associated with this, the uglier the style, the “harder” the story claims to be: paying attention to language is for sissies. So is witty dialogue and characters that are more than cardboard cutouts. If someone points such problems out, a common response is “It’s a novel of ideas!” The originality of these ideas is often moot: for example, AIs and robots agonizing over their potential humanity stopped being novel after, oh, Metropolis. Even if a concept is blinding in its brilliance, it still requires subtlety and dexterity to write such a story without it devolving into a manual or a tract. Among other things, technology tends to be integral in a society even if it’s disruptive, and therefore it’s almost invariably submerged. When was the last time someone explained at length in a fiction piece (a readable one) how a phone works? Most of us have a hazy idea at best how our tools work, even if our lives depend on such knowledge.

To be fair, most writers start with the best of intentions as well as some talent. But as soon as they or their editors contract sequelitis, they often start to rely on shorthand as much as if they were writing fanfiction (which many do in its sanctioned form, as tie-ins or posthumous publication of rough notes as “polished products”). Once they become known names, some authors rest on their laurels, forgetting that this is the wrong part of the anatomy for placing wreaths.

Of course, much of this boils down to personal taste, mood of the moment and small- and large-scale context. However, some of it is the “girl cooties” issue: in parallel with other domains, as more and more women have entered speculative fiction, what remains “truly masculine” — and hence suitable for the drum and chest beatings of Tin… er, Iron Johns — has narrowed. Women write rousing space operas: Cherryh and Friedman are only the most prominent names in a veritable flood. Women write hard nuts-and-bolts SF, starting with Sheldon, aka Tiptree, and continuing with too many names to list. Women write cyberpunk, including noir near-future dystopias (Scott, anyone?). What’s a boy to do?

Some boys decide to grow up and become snacho men or, at least, competent writers whose works are enjoyable if not always challenging. Others retreat to their treehouse, where they play with inflatable toys and tell each other how them uppity girls and their attendant metrosexual zombies bring down standards: they don’t appreciate fart jokes and after about a week they get bored looking at screwdrivers of various sizes. Plus they talk constantly and use such nasty words as celadon and susurrus! And what about the sensawunda?

Some boys decide to grow up and become snacho men or, at least, competent writers whose works are enjoyable if not always challenging. Others retreat to their treehouse, where they play with inflatable toys and tell each other how them uppity girls and their attendant metrosexual zombies bring down standards: they don’t appreciate fart jokes and after about a week they get bored looking at screwdrivers of various sizes. Plus they talk constantly and use such nasty words as celadon and susurrus! And what about the sensawunda?

I could point out that the sense of wonder so extolled in Leaden Era SF contained (un)healthy doses of Manifesty Destiny. But having said that, I’ll add that a true sense of wonder is a real requirement for humans, and not that high up in the hierarchy of needs, either. We don’t do well if we cannot dream the paths before us and, by dreaming, help shape them.

I know this sense of wonder in my marrow. I felt it when I read off the nucleotides of the human gene I cloned and sequenced by hand. I feel it whenever I see pictures sent by the Voyagers, photos of Sojourner leaving its human-proxy steps on Mars. I feel it whenever they unearth a brittle parchment that might help us decipher Linear A. This burning desire to know, to discover, to explore, drives the astrogators: the scientists, the engineers, the artists, the creators. The real thing is addictive, once you’ve experienced it. And like the extended orgasm it resembles, it cannot be faked unless you do such faking for a living.

This sense of wonder, which I deem as crucial in speculative fiction as basic scientific literacy and good writing, is not tied to nuts and bolts. It’s tied to how we view the world. We can stride out to meet and greet it in all its danger, complexity and glory. Or we can hunker in our bunkers, like Gollum in his dank cave and hiss how those nasty hobbitses stole our preciouss.

SF isn’t imploding because it lost the fake/d sensawunda that stood in for real imaginative dreaming, just as NASA isn’t imploding because its engineers are not competent (well, there was that metric conversion mixup…). NASA, like the boys in the SF treehouse, is imploding because it forgot — or never learned — to tell stories. Its mandarins deemed that mesmerizing stories were not manly. Yet it’s the stories that form and guide principles, ask questions that unite and catalyze, make people willing to spend their lives on knowledge quests. If the stories are compelling, their readers will remember them after they finish them. And that long dreaming will lead them to create the nuts and bolts that will launch starships.

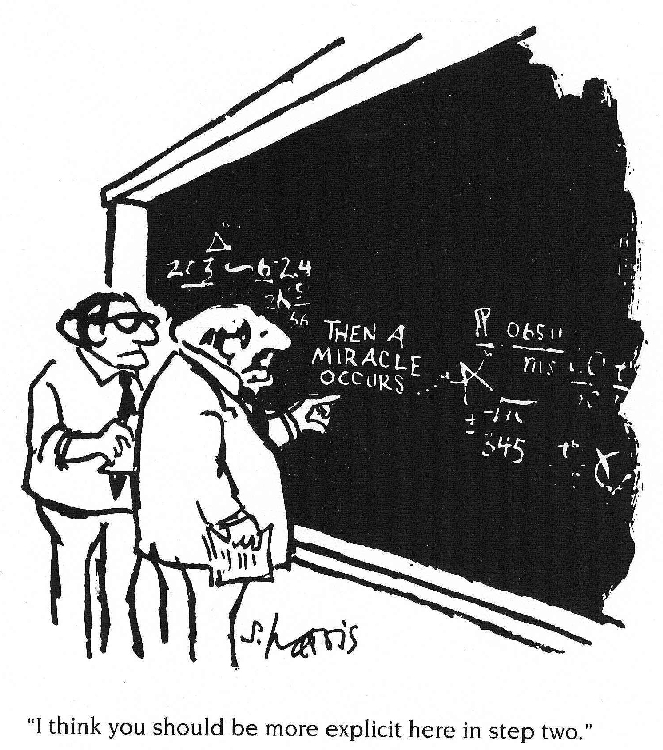

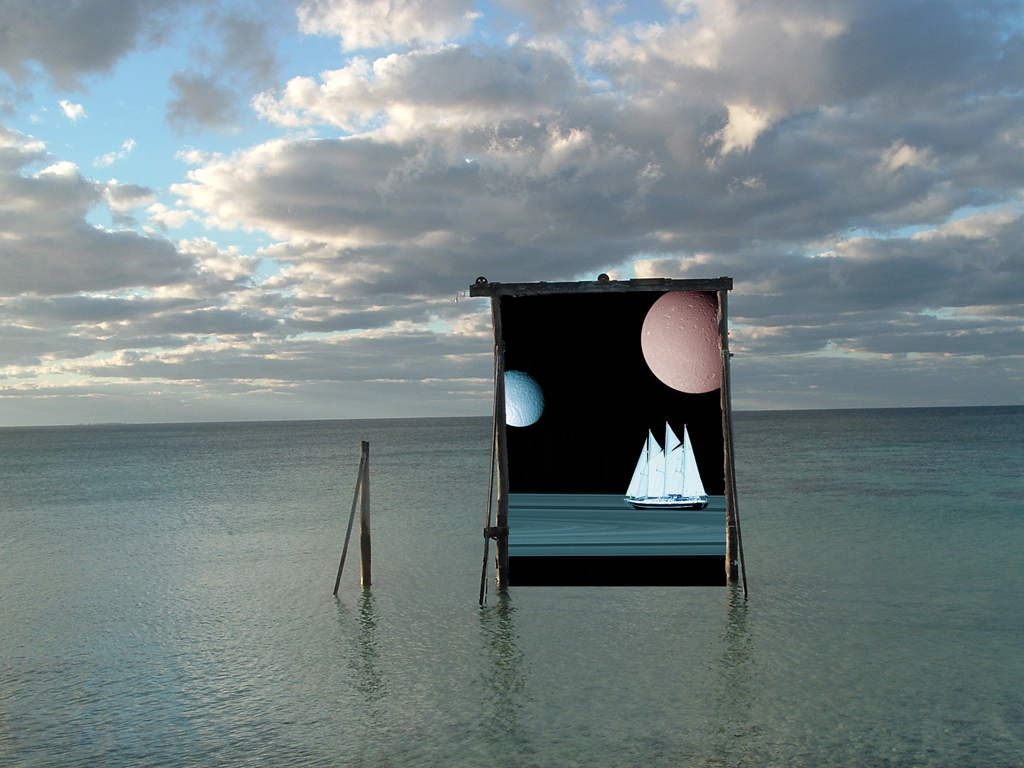

Images: 1st, Stormtrooper Walking from Grimm’s Pictures; 2nd, the justly famous Sidney Harris classic from What’s So Funny About Science?; 3rd, Jim Parsons, The Big Bang Theory’s Sheldon Cooper, photo by Robert Trachtenberg for Rolling Stone; 4th, The Gate, by Peter Cassidy.

Note: This is part of a lengthening series on the tangled web of interactions between science, SF and fiction. Previous rounds:

Why Science Needs SF

Why SF Needs Science

Why SF Needs Empathy

Why SF Needs Literacy

Why SF Needs Others

I guess this one might be called Why SF Needs Fiction!

Even if a concept is blinding in its brilliance, it still requires subtlety and dexterity to write such a story without it devolving into a manual or a tract.

SUCH an important thing to remember!

I was amused that you chose the word susurrus because it’s one of the words that I *do* notice come up repeatedly in fantasy stories, to the degree that when it does, I automatically pull back. The other word that does this to me is coruscation. They’re both excellent words, but kind of like diamonds–part of their value lies in rarity, and when they’re used a lot, the rarity’s lost.

The photo at the bottom–by Peter!–is gorgeous. Is the picture in the easel a ship sailing on the hydrocarbon seas of Titan?

Hehe! That’s exactly why I used it — because too much beautiful language without the other accessories is also not good.

The photo is actually an old harbor gantry in the Australian reef, I’ll send you the unadorned original. The little yacht is sailing on Saturn’s rings. Peter took the photo, and he also did the composition in Photoshop with some help from yours truly.

Let’s call soft sci-fi what it is and be done with it: fantasy.

Despite the myriad personal problems Orson Scott Card possesses, he does produce the clearest distinction between sci-fi and fantasy I’ve ever come across: science fiction is about forging order out of chaos while fantasy is about breaking established order in order to re-establish freedom. Naturally the former is best suited to science which functions because the universe itself functions according to laws and logic, while the latter is identified with magic which is defined by its defiance of said laws.

This distinction is important when we consider the role of hard vs. soft science fiction. Hard science fiction is about finding our place in the universe, whether that means filling in the blank spaces on a cosmological map or exploring the ramifications of immortality (say by isolating genetic sequences that affect aging). This type of science fiction attempts to both address potential problems and to charge us with facing them. If it ignores science disingenuously it betrays its mission; any answers it provides are as suspect as the “facts” they are based on.

Fantasy is about exploring ourselves and our humanity. Fantasy tends to be much more personal, psychological, or sociological than science fiction (this is not to say that science fiction does not or cannot utilize characterization, merely that said characterization serves a different role). Both a science fiction story and a fantasy story may deal with an evil and corrupt government, but typically the fantasy solution will be an overthrow of the government (or at least the head of it) while science fiction will leave the government to explore a new frontier to make a better society. Because fantasy is less interested with problems and solutions than it is with themes, accuracy is not requisite to the success of its message so long as it is internally consistent.

The long-running observation is that Star Wars, the ultimate soft style science fiction movie, is not actually science fiction but fantasy – and why not: there are knights, wizards, magic powers, enchanted swords, noble blood lines, ancient religious orders, etc. – and it is consistent with the theme of overthrowing an established order (and a legitimate one at that) in favor of freedom. Moreover, the themes in Star Wars are about personal growth and responsibility. Luke doesn’t destroy the Death Star by training to become a great pilot and master the mathematics, physics, and engineering it requires, but by accepting his destiny and embracing a personal legacy. He defeats Vader by accepting his father and choosing a path of non-violence, even if it leads to his death, rather than subjugating his will to that of a corrupt government (the less said about the prequels the better. You’ve already done so far better than I could have).

But we see this with other soft science fiction. Star Trek is the most egregious of using technology as magic, but the franchise has always been at its best when dealing with personal stories rather than epic space opera. Ben Bova’s Orion series despite containing space ships, lasers, and other future technologies was never interested in exploring what a world with those technologies was like so much as why were compelled to explore them in the first place. Arthur C. Clarke is wonderful at jumping from sci-fi to fantasy and back, and by noting how much technical descriptions he provides (albeit, usually only in physics) one can instantly tell what sort of story we’re going to get: Rendezvous with Rama or Childhood’s End.

Do soft science fiction fans get upset when you refer to their stories as fantasy? Absolutely, but so what? The stories are there and the stories are legitimate. They contain ideas worth exploring and tales worth telling populated by characters worth knowing. Perhaps not in all the books or even most, but I know of not one genre where the majority are worthy of acclaim; if soft science fiction gets it wrong sometimes, at least it’s good company. Referring to it as fantasy, however, frees it from the duty to be accurate and gives the reader the right to ignore it if accuracy is critical to the reader, the author, or the message.

“Hard science fiction is about finding our place in the universe. Fantasy is about exploring ourselves and our humanity.” I submit those two are not so neatly split, and as one example consider Tiptree’s Houston, Houston, Do You Read? or, better yet, A Momentary Taste of Being.

My solution would be different from yours: I’d call everything speculative fiction, and be done with splitting hairs and assigning relative values. Then we wouldn’t have those frankly pointless arguments about whether Atwood, Le Guin, Borges or Calvino are authors of literary or speculative fiction. I discussed this further (and from a different angle) in SF Goes McDonald’s: Less Taste, More Gristle.

I don’t think it’s a clean break, nor should it be. While dichotomy is a useful tool it is also a destructive one – one cannot break the world in two without breaking the world. To keep the categories useful but not destructive we simply need to acknowledge that a piece of fiction may exist in both. My favorite example would be Carl Sagan’s Contact.

The problem with simply labeling everything as speculative fiction and ending the discussion there is it fails to resolve or even address the question of scientific accuracy. By considering literature in terms of order-themes vs. chaos-themes (all D&D alignment jokes aside, please) scientific accuracy comes into its own as distinctly relevant or irrelevant to the story. Someone looking for scientific accuracy in Tolkien is missing the point just as someone ignoring the accuracy depicted in Sagan misses the message (that all of this IS possible and so we should keep searching).

I doubt you can accuse me of ending such discussions, Alex, when I’ve written half a dozen articles on the topic! *laughs* My ever-lengthening series on speculative fiction includes one essay that specifically argues for the absolute necessity of scientific grounding in the genre. It contains the following sentences: “If a story contravenes or doesn’t depend on science, real or speculative, it’s not SF. It’s magic realism or fantasy. Not that it matters, as long as the plot and characters are compelling.” So in many ways — in fact, most ways — you and I agree.

However, consider a discussion about cooking. There are thousands of cuisines. Each has countless nuances, and many shade into each other as well. Both “science” and “art” are involved in it, and both are crucial. Having people say “X cuisine brings down cooking standards” (jokes about British cooking aside) is neither accurate nor constructive. My latest article arose because someone (several someones) said that about SF — and did so invoking “hard” SF as a sacrosanct concept, when it’s clear to scientists who love the genre that there is really no “hard” SF. Instead, there are infinite shades of scientific rigor within the larger genre.

I read Sagan’s Contact. You can practically hear the clunks thudding. The film was in my opinion better because its unavoidable simplifications (and Jodie Foster!) masked the book’s deficiencies. On the other hand, if you read Italo Calvino’s Elements, Andrea Barrett’s Ship Fever or Karl Iagnemma’s The Nature of Human Romantic Interactions, you see a seamless fusion of nuanced art with accurate science.

Order versus chaos is an interesting categorization scheme and has a lot of merit, but science is not just a law-and-order tool. It’s true there are patterns in the universe, it’s not an arbitrary jumble — and, furthermore, our brain evolved to discern and comprehend them (up to a point; we are not really equipped to understand the very small and the very large, which is why mysticism often creeps in at those scales). However, science is also an instrument of subversion and change, because it constantly seeks to discover and understand more, often overturning older paradigms. As scientists quip, “Theories start as heresies and end as superstitions.”

Finally, some of this may be related to age. When people and science are young, they want to take things apart and see how they tick. Later on, they want to put them back together and see if they can coax the reconstructions into ticking.

Wow, a lot of good stuff to unpack here, Athena. You cover a lot of important ground.

James Gunn suggests that traditional literature is the literature of continuity, that fantasy is the literature of difference, while science fiction is the literature of change.

All fiction is a machine to provoke an emotional response. Science fiction is fiction that provokes a response to the world changing around us. It is science fiction because science and technology have become for us clear markers of change.

I propose that “hard science fiction” is fiction designed to provoke an emotional response primarily to the science, technology, and world building, not to the characters, not to the plot. This is why we perceive Niven’s Ringworld as hard SF, even though it scientifically outlandish not in one detail but in nearly every detail, while Kim Stanley Robinson’s Red Mars, a meticulously researched novel populated by scientists, is not. In order to provoke the desired emotional response the science must be sciency enough, but beyond that thin veil little more is required.

Laura, I’m happy you liked it! I ended up stinting on some points, because the essay was getting long. But I suspect I’ll keep revisiting the topic.

Calvin, that’s an interesting proposal regarding what to call “hard” SF. Perhaps the best yet, other things being equal (that is, a respectable show of scientific rigor in a story). Gunn’s suggestion is a touch too facile, specifically in connection with traditional literature. Think of Woolf and Joyce in our century, and how seismically they shifted literary fiction.

Well, any brief definition is going to be facile, in my opinion. Genres are complicated, wooly things, best described by pools of tropes, not neatly axiomatic definitions.

Complicated and unwieldy, like biology! *laughs*

Athena said:

“Gunn’s suggestion is a touch too facile, specifically in connection with traditional literature. Think of Woolf and Joyce in our century, and how seismically they shifted literary fiction.”

Not to mention that every single generation has reintrepreted the classics to suit their own needs, discovering fascinating ways of looking at old legends through new prisms of thought (look no further than the Arturian legend and its über-reimagining by Tolkien with Aragorn as the Once and Future King).

And if traditional literature is indeed the literature of continuity, then, it is even more important that we know it. Only by knowing the past can we question the present and imagine the future, the last being the basis of Science Fiction.

I will leave you with these merged quotes from the movie Gladiator, which, put together, convey a wealth of meaning:

“We are but shadows and dust, yet what we do in life echoes in eternity.”

Cheers,

Eloise 🙂

One needs to unpack Gunn’s quip to see what it means–I usually devote an entire lecture to it. By ‘literature of continuity’ he means (I think) that traditional literature is connected to the here-and-now. Even the examples of Woolf and Joyce fall into that.

Fantasy is the ‘literature of difference’ because it postulates a world that is in a fundamental way different and unreachable from the here-and-now. Harry Potter (soon to be discussed in an upcoming essay) is discontinuous from our world.

Science fiction is the ‘literature of change’ because, first, while it postulates a world different from the here-and-now, that difference is supposed to be possible or plausible; furthermore, science fiction focuses on the effect of that change on us. Kim Stanley Robinson adds his own remark that “science fiction is the history that we cannot know.’

I see Gunn’s remark as a description, not a definition. By this I mean it should not be used as a dividing line, but as a tool to help us better understand how and why science fiction and fantasy evoke different responses in us.

I did hear another quip at a convention about the difference between fantasy and science fiction, which I’ll modify to include ‘traditional’ literature:

traditional literature: what if a boy wished he could fly?

fantasy: what if a boy could fly?

science fiction: what if everyone could fly?

Eloise, I agree. If the stories resonate powerfully, they get re-invented across eras. The Arturian cycle started as a Celtic myth that has undergone at least three cultural transmutations, to say nothing of the endless literary retellings.

Calvin — when unpacked, Gunn’s definition makes more sense. I interpreted “continuity” to mean what is already known in terms of both content and style.

I think your closing quip could evolve even further, though it would make it unwieldy! All literature can (and does) ask “what if someone wished they would fly?” My modified replies show the obvious leakage across genres, depending on the details of how.

Traditional: What if they built a flying machine, or spent their lives yearning after this dream?

Fantasy: What if they grew wings? [alone among their kind, without any help but wishing or a kindly fairy godmother]

Science fiction: What if they grew wings? [as part of the growing cycle of their species, or with the aid of technology]

I wish I could hear your lectures!

Exactly! There are too many examples of SF, including many that are typically regarded as masterpieces of the genre, where this is so. All I remember from Ringworld is that there was a very large impossible artifact in it. I can’t really remember much of the plot or characters at all, and didn’t especially enjoy it at the time I was reading it. Farscape on the other hand, which is basically “space fantasy”, was for me a far more successful and enjoyable story in a large part because the focus was mainly on the characters rather than on the big dumb objects in the background.

In my experience, “hard SF” seems to be particularly bad at this, which is a shame since some of the ideas that get played with can be pretty interesting. But without a good story, and especially without good characters, it lacks staying power.

Andy, absolutely! If the characters are vivid enough that we care for them, we never forget the story. Here’s the closing of another essay in the series:

“Most fiction works are slated for oblivion. “Cool” concepts date fast, genre fashions even faster. But storytellers who see into others’ minds create characters that haunt and compel us, whose actions and fates matter to us. Through them, they burst past genre confines to make great literature that is long remembered, retold and sung.”

One of my pet peeves! I agree that that is at least in part due to “girl cooties”.

But I think that what many people think of as “hard” science fiction is actually heavily reliant on technology and engineering, as opposed to science. Physics gets included, but I suspect that’s the science that can most easily be appreciated by electrical and mechanical engineers. And the lack of squooshy bits in physics experiments (only lasers! and telescopes! and atom smashers!) makes it a manly science to boot!

You and me both, Peggy. I’m tired to death of people equating science with physics. You’re right, too, about the conflation of techno/engineering with science and manliness.

Andy said:

“Farscape on the other hand, which is basically “space fantasy”, was for me a far more successful and enjoyable story in a large part because the focus was mainly on the characters rather than on the big dumb objects in the background.”

For me as well; the aspect of the character arcs are one of the foremost reasons I continue to enjoy the series.

The essay itself is rich and insightful as always, and touches on more than a few good points regarding the literary genres of traditional, fantasy and science fiction and the ways the lines between them often can and do blur. Great stuff — and beautiful photo by Peter!

The essay got extensively quoted in Futurismic, so I guess I have more lurkers than I realized!

I’m glad you liked the photo, dear Heather. It’s one of my favorites, as well. The Great Barrier Reef is indeed as otherworldly as that and I felt that Peter’s photo does justice to it. You may recall that I used a different photo of this series as a background to the two tehári (Adhísa Sóran-Kerís and Penirén Táren) in Spider Silk.

Wow! Fantastic post and comments, to all!

I don’t have anything to add. I just enjoyed the essay and the comments.

TK

Welcome to The Reckless, TK!

By date this may be old, but it’s newly read. (It may be peculiar but sampling archives works for me.) Two points come to mind.

First, more trivially in one sense, you don’t have to be J.D. Bernal to put technology and science together. The notion that an interest in machinery is manly implies a disinterest in machinery is unmanly, aka womanly. Which is largely a cliche, inasmuch as the overwhelming majority of people, male or female, are no more interested in the innards of machinery than they are in their own innards. I find most people are far more interested in character than anything about the natural world. (Lest the social sciences feel dissed, I should add that most people are not interested in the past, the future or other societies. Or even in thinking about this society as a whole, rather than about individuals.)

Second, also a trivial point, but in a different way, Farscape’s characters are commonly hailed as compelling. I find that I couldn’t make heads nor tails of them in the end. Was Crichton a brilliant scientist or a pop culture hip jock bumbling through? What was Crais about? Was Dargo the super-Klingon “hyperrage” badass or the bromance of Crichton’s life? Was the blue woman a wise and good earth mother sorceress or ruthless and conniving? How did Aeryn’s thinking about the Peacekeepers (if any,) change? And how did she distinguish between Johns? Was the gray girl really a sexual libertine incarnating a rejection of American puritanism or was she just a bad girl gone good when she hooked up with Dargo? It seems to me that most of the acted characters on Farscape had at least two personalities in reserve for the writers to use. This sort of thing is why I’m never quite sure what “character” means in critical discussion.

Your point about what interests people is precisely my conclusion to the article: in the end, people want stories with characters whose fate matters to them. The rest is enriching and welcome, but ancillary.

I saw Farscape sporadically, so I’m not in a position to do an exhaustive critical analysis of the series. Having the characters dual as you describe (which rings true with my own impressions) did leave writers with leeway. In both film and writing, characters are frequently “slaved” to plot convenience and Farscape is no exception (though Crichton was more a hip jock in my eyes).

I always read the “hard” and “soft” SF descriptions as “hard” SF dealing mainly with “hard” sciences and “soft” sciences dealing with well, “soft” sciences (sociology, economics, etc.).

LeGuin’s Left Hand of Darkness would be “soft” SF, in that it deals with the sociological impact of certain changes, not the mechanics themselves.

Left Hand of Darkness deals with biology and its repercussions. So unless you consider biology “soft”, it’s fairly traditional hard SF. Its sole difference from Leaden Age “hard” SF is that it doesn’t bristle with gizmos and handwaving about its underpinnings (and as a result has aged far better than works that do).