Opening note: This topic obviously changes at near-lightspeed, but the essential facts in the essay won’t change. I wrote it thinking as both research scientist and citizen of the world. I’ve chosen not to use any images this once, the text must be the focus; and because of rapid developments, links to primary sources would be too cumbersome to keep up to date.

The Angel of Death Touches All Doors

As humanity stumbles and reels under the SARS-CoV-2 (CoV-2) assault, the grimmest failure of this dark hour is executive abandonment of the responsibility to inform polities (which right now includes just about all of us, everywhere) of the nature of the threats at their gates and the costs of the choices before them. The nonfeasance is an unforgivable omission because of the rich and instructive history of the 1918 influenza outbreak and the substantial advances in the epidemiological and virological disciplines since that epidemic took the lives of some 50 million.

The decision tree we must establish and act upon could mean the difference between effectively containing COVID-19 mortality and collateral fallout or enduring losses of the scale our parents and grandparents witnessed 100 years ago.

The damage that will be done because of our collective failure to frame our choices responsibly, and act on them with alacrity and precision, will not only determine how many lives will be saved or lost. As importantly, and here is where the omissions we are writing off as mere political disagreements enter the equation, it will inform the body of crucial knowledge that we provide to future generations who will confront stealthy interlopers like CoV-2—or worse. Sadly, the (approximate) prosperity of the First World from 1950 to 2000 and its evolved medical technology allowed stupidity with near-zero consequences.

In the absence of a comprehensive assessment, I’ve undertaken a brief review of papers and researchers’ discussions of the programmatic response choices before us at successive levels. We’ve never been richer in resources to confront the CoV-2 menace, but the fly in this therapeutic ointment is that political talent and principles trail their scientific equivalents. This, incidentally, is also true of other clouds on the horizon of our civilization, like climate change; but CoV-2 is literally staring us in the face in ways that are impossible to ignore or finesse.

The Nature of the Beast Tells Us the Dimensions of Its Cage

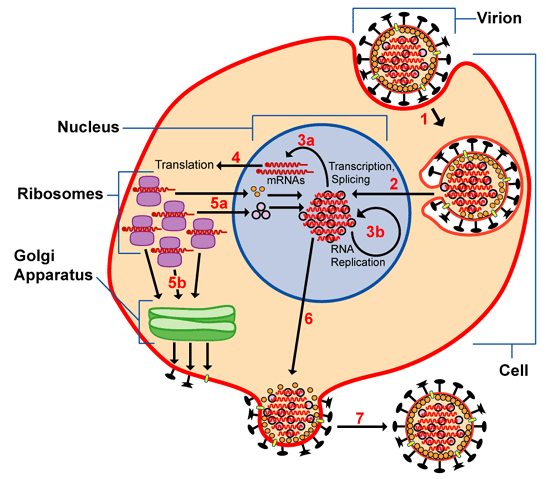

By now everyone knows that CoV-2 is an RNA virus whose surface glycoprotein (spike S1/S2) attaches to cell receptor ACE2 (angiotensin-converting enzyme-2, a regulator of function in lung, heart, kidney and GI tract). CoV-2 is a close relative of SARS and MERS, with bats as its primary reservoir. The fact that it’s an RNA virus means that it can mutate rapidly, though CoV-2 seems to do so on a slow scale; other RNA viruses include hepatitis C, Ebola, HIV, polio, and influenza.

Like other viruses that bedevil humanity, CoV-2 is zoonotic: systematic human encroachments on ecosystems and the appetite of the rich for prestige-exotic animal food are major engines behind the species jumps. But CoV-2 has characteristics that make it a perfect predator of a species whose brain is not good at statistics and that has become dependent on an unusually long run of good luck—which allowed such dangerously destructive behavior as the flourishing of anti-vaccine movements not only in fundamentalist communities but also in “educated” elite enclaves. SARS, MERS and Ebola are far more virulent, but they don’t spread by aerosols nor from pre-symptomatic carriers as does CoV-2; and they kill hosts so quickly that even symptomatic carriers have few contacts. H1N1 flu (the 2009 burst) and the other flu viruses spread easily via aerosols like CoV-2, but are far less virulent and produce symptoms much faster, allowing rapid alerts.

Two possible treatments put early on the table for CoV-2 were hydroxychloroquine, an antimalarial drug (also used for lupus and arthritis) that blocks the release of viral RNA into host cells; and remdesivir, an adenosine analog that gets used by viral RNA polymerases, short-circuiting viral replication, originally developed to treat Ebola, Marburg & MERS.

From these clinical trials remdesivir is known to be non-toxic, and the CoV-2 polymerase is close enough to its original targets to be successfully decoyed. Hydroxychloroquine is established but has some alarming side effects: cardiac arrhythmia that can be lethal (which means doses must be carefully calibrated according to weight), permanent retinal or kidney damage (increased chances if used long-term). The reservations around hydroxychloroquine proved correct, whereas non-blind remdesivir trials have raised cautious optimism, made trustworthier by its creator company’s collaboration with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).

High-gear efforts to develop vaccines are also proceeding apace—there are at least 90 ongoing projects—with the Oxford University and Moderna candidates leading the pack.

Demagogic effusions aside, at this point we have no drug or vaccine that’s effective against CoV-2. It is possible we may never get one, as is the case with many RNA viruses due to their rapid mutation rate. As an example, we never developed an HIV vaccine; AIDS has been turned into a chronic disease instead of a death sentence by antivirals, for those who can afford them—but the HIV transmission route has a far higher threshold than the simple exhalation sufficient for CoV-2.

The scientific complexities around a vaccine are dizzying: selection of viral target, choice of methodology (protein or nucleic acid based? dead or weakened live virus?), decision on delivery vehicle; then testing for efficacy and safety, preferably in double-blind studies, first in animals, then in humans.

Just looking at this very partial list, one can tell why a wildly optimistic window for developing a vaccine exceeds a year. The only advantage in this round is that there were vaccines on the way for CoV-2 cousins SARS and MERS (abandoned part-way for lack of funding when the outbreaks got contained), so the effort can resume instead of getting started from zero.

Magic Bullets Are Delivered by Trains and Traded by Mortals—When the Shouting Stops

If/when we do get a vaccine, the issues of side effects, correct dose and stage of administering, scaling up, distribution and pay structuring will remain formidable. It has become painfully clear that the federal US administration knows little and cares less about any of these aspects, pitting state governors against each other according to their ethics and abilities. But at least if we do discover or create effective tools, we’ll have a real chance to undo this Gordian knot—and hope will have to serve as a prop until we can all line up for the sip or jab that saves.

Put simply, the current global strategy is based on the fact that lockdowns slow down the infection rate enough to give healthcare systems leeway to handle cases without buckling; they also give time for development of coordinated, robust long-term protocols. This was the strategy in 1918 as well. This response, the sole one possible in the absence of a vaccine, nevertheless puts horrific triaging onuses on medical personnel, themselves at highly increased risk of death from constant exposure, especially with inadequate protective equipment—and tilts lethality to people whose livelihood does not afford them the luxury of remote work.

Systematic lockdowns have unquestionably flattened infection and lethality rates, but they’re also causing enormous suffering beyond often-irreversible economic carnages and hardships: people are dying from non-coronavirus causes (bone fractures, tooth abscesses, eclampsia, strokes, heart attacks, inflamed appendices and gall bladders, blood pressure and glucose spikes…) because they’re either afraid to go near a medical facility or must resort to an overwhelmed one.

There are also the rising specters of collapses in mental health and general wellbeing, as well as the inevitable surges in domestic abuse and race/age profiling. On the other side of this Janus gate, re-opening too soon will result in secondary spikes with people literally dropping dead in offices and public places—and until tests for present and past infection become highly reliable and readily accessible, there are no guarantees or protections against successive outbreak cycles.

On the third hand, effective lockdowns will significantly slow down the development of herd immunity, which can come about from either systematic vaccination or the appallingly brutal path of random chance. The effective CoV-2 immunity threshold is calculated to be 70% infection, and the inadvertently fully-contained experiment of the Diamond Princess pins the CoV-2 total fatality rate at ~1.3%, which makes it at least 10x more virulent than the slippery “common” flu. Putting the two together, immunity-by-luck would mean potential deaths of 80 million globally—comparable to the 1918 pandemic numbers. Furthermore, as the flu has taught us, immunity to RNA viruses is transient due to their high mutation rate. So if we want our world to ever resemble what it once was, we must develop a vaccine—though it will require regular renewals, and we don’t yet know the length of immunity to CoV-2.

The Costs of Living With Something Less Dispositive Than ‘Winning’

CoV-2 testing is a huge muddy pit right now. For one, each nation is using widely different criteria for test eligibility and reporting methodology (which explains, for example, why conscientious Belgium’s numbers are so high, whereas most countries tried to suppress the appalling tolls from nursing homes and hospices). There are two broad categories of tests nominally available: RT-PCR checks for CoV-2 RNA and targets current infection; antibody checks for antibodies against unique CoV-2 protein regions and targets past infection. For dependable accuracy, they need to be both sensitive and specific in the 99% range. These two stringent and partially-competing requirements already indicate that national plans to issue “clean health” passport equivalents are near-certain recipes for medical and civic disasters.

By their intrinsics, PCR tests are so sensitive that they can generate false positives from RNA fragments of inactive virus being shedded or harmlessly floating in the body. This is almost certainly the explanation for the “re-infection” alarms from South Korea, who did well to err on the side of excessive caution of interpretation. Antibody reagents can cross-react with proteins from related viruses (recall that CoV-2 belongs to the SARS family) and the pressure for getting them released has led to a glut of variants on the market, many of whom haven’t been subjected to independent quality controls.

It’s crucial to know how long it takes for antibodies to appear post-infection and how long they persist. Errors in the former would lead to false negatives; in the latter to a false sense of security. But the (not yet peer-reviewed) Chinese study that pronounced total absence of antibodies in 6% of recovered COVID-19 cases is almost certainly mistaken. As Dr. Fauci said, lack of post-infection antibodies would be unprecedented—and CoV-2 is still a regular virus, not a Frankenstein monster. This is true despite the political wish, especially in the US, to classify CoV-2 as a consciously created bioweapon, against all the evidence gathered by intelligence agencies; the only weaponization here is the desire to distract US voters in a pivotal election year.

Tracing protocols worked for Taiwan and South Korea, nations that are small, homogeneous and have a record of trusting (or, at least, obeying) their rulers…and, to my continuing surprise, draconian lockdowns also worked in my native Greece. Tracing poses a raft of questions about privacy and policing, and neither governmental nor private venues of such panopticons have covered themselves with glory in this matter.

Isolation and confinement, our sole instruments in this fight so far, go against both fight-or-flight reflexes and cortical emotions. For so counterintuitive a strategy, we need composure, self-discipline and an advanced sense of communal involvement and responsibility. But it’s clear that the US is already getting restive, with thugs brandishing assault weapons storming state houses. The expression “Blue Lives Matter”, once meant as a solidarity shout-out to police personnel, has acquired a whole new meaning after the cynical activation of fringe power bases. Anger is justified, but it should be laid at the doorstep of the White House and the Senate. And (too) many people in the US still believe that death will only harvest the “old and weak”, not having read any history.

Viruses are totally indifferent to borders, political parties, religious convictions, celebrity or riches—though the rich and powerful will continue to have far better access to life-saving care and first dibs at any effective treatment. Our civilization remained recognizable after the 1918 outbreak, (10% fatality, minimum estimate), and quasi-recognizable after the Black Plague (30%). In marked contrast, the native civilizations of the Americas (90% fatality) not only disappeared after the European-introduced pandemics, but their existence and achievements were nearly forgotten—perhaps because that served the claims and consciences of the inheritors.

The universe is not hostile but indifferent, and it is not ruled by a divine gaze that “sees all” and weighs individual fates on balances…which means that the collective responsibility for our path remains entirely with us. Prayers and scapegoats won’t avail us. What’s in our favor now is our scientific knowledge and lessons of the relatively recent past, which nevertheless require principled and intelligent will to be effectively deployed.

After the best Athenian minds had been lost to the plague during the first Peloponnesian War, the attempt to divert attention with facile political/military tricks cost that renowned city-state not just its primacy but, eventually, its sovereignty and geopolitical existence. In the end, only coordinated scientific effort—and trust in its practitioners—will save from the worst choices, including failing to make any that leverage all the resources we have at hand this time around. Those of us who meet on the other side of the shore will rebuild the world, as our predecessors did so many times, provided we don’t pass an irreversible turning point. Perhaps this time we won’t forget the lessons we got taught by reality, although human intelligence avoids unpleasant memories. This, too, is a survival tactic—though not an ideal one for shaping long-term solutions.