The Andreadis Unibrow Theory of Art

After my second article about Cameron’s Avatar, a young British media critic who occasionally visited my blog accused me of snobbery. He stated that my points about entertainment like Avatar went past aesthetics and “devolved into” political and moral pronouncements about people who like what he considers lowbrow art (he assumes I share his definition of lowbrow, of which more anon). He further opined that classes of artful brows are just peer pressure. Hence Cameron is as good as Ozu unless you “drip with disdain” for the hoi polloi.

After my second article about Cameron’s Avatar, a young British media critic who occasionally visited my blog accused me of snobbery. He stated that my points about entertainment like Avatar went past aesthetics and “devolved into” political and moral pronouncements about people who like what he considers lowbrow art (he assumes I share his definition of lowbrow, of which more anon). He further opined that classes of artful brows are just peer pressure. Hence Cameron is as good as Ozu unless you “drip with disdain” for the hoi polloi.

In the article that started this discussion I primarily discussed biological drives. I posited that certain types of entertainment arouse the fight-or-flight response and repeated immersion in them can lead to PTSD pathology, including mob-like behavior. The argument that art is ever devoid of politics and (at least implicit) moral judgments is either naïve or disingenuous and my critic doesn’t strike me as the former. I suspect that his cultural background, awash in class distinctions and reverberations of colonialism, may partly explain his viewpoint. Even more fundamentally, however, I think his definition of lowbrow art differs so much from mine that we are really discussing orthogonal concepts.

So I’m taking this opportunity to articulate my art classification scheme. To give you the punchline first, my definitions have to do with the artist’s attitude towards her/his medium and audience and with the complexity and layering of the artwork’s content, rather than its accessibility. In my book, lazy shallow art is low, whether it’s in barns or galleries. What makes Avatar low art is not its popularity, but its conceptual crudity and its contempt for its sources and its viewers’ intelligence.

A common if usually implicit assumption is that quality and popularity are mutually exclusive. Hence, “lowbrow” is often considered synonymous with mass appeal: bestsellers, platinum albums, blockbuster films. Yet you can have wildly popular art that is light years away from least common denominations. Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose comes immediately to mind; so do Alvin Ailey Dance Theater and flamenco; Peter Gabriel and Dire Straits (including their groundbreaking MTV videos); RPG games like Gabriel Knight, Myst and Syberia; and shows about nature or archaeological findings (as accessible “reality TV” as you can get) – or, for that matter, the cordon bleu-quality food you can buy cheaply in corner stores of any French or Italian provincial town.

My admittedly idiosyncratic definition comes from a cultural upbringing that makes no rigid high/low distinctions. Hellenes still read Homer and watch Eurypides and Aristophanes for entertainment. To use a parallel from my critic’s culture, Shakespeare and Dickens were not highbrow in their eras. People of all classes watched Elizabethan plays in open-air theaters and Dickens’ serialized novels were the Victorian equivalents of soap operas. Too, a lot of poetry, including that of Nobel-prize winners, has been set to compulsively singable music by Hellene popular composers – and the songs are sung across Hellas independently of social stratum.

My admittedly idiosyncratic definition comes from a cultural upbringing that makes no rigid high/low distinctions. Hellenes still read Homer and watch Eurypides and Aristophanes for entertainment. To use a parallel from my critic’s culture, Shakespeare and Dickens were not highbrow in their eras. People of all classes watched Elizabethan plays in open-air theaters and Dickens’ serialized novels were the Victorian equivalents of soap operas. Too, a lot of poetry, including that of Nobel-prize winners, has been set to compulsively singable music by Hellene popular composers – and the songs are sung across Hellas independently of social stratum.

Along similar (lack of) demarcations, there are no bestsellers or blockbusters in Hellas. Books are printed in small runs and are not warehoused or pulped. As a result, editors take chances on unknown authors but spend nothing on PR, and people aren’t trained to restrict their reading to genres. Nor are films split between hothouse esoterics distributed solely to hoity-toity boutique venues versus “crowd-pleasers” shown in every mall (besides, Hellas doesn’t have malls – it has small shopping courtyards). Finally, we live literally on top of several breathtaking, radically different past cultures, from Minoan to Byzantine. So our sensibilities tend to the syncretic.

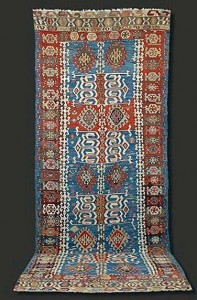

Most cultures, if not terminally debased, have art woven integrally into the lives of their people. Folk art and craft are often extraordinarily sophisticated both in style and content: clothing, jewelry, utensils, instruments, furniture, dwellings, gardens, cooking, painting, dance, music can all be high art – yet they are part of daily life, not exhibited on museum walls or opulent stagings for the few. This is important not only in itself, but also because such art was/is created disproportionately by women. In such settings, artists/artisans are often political and moral forces to be reckoned with: builders and smiths, storytellers and bards. In some nations they are honored as living monuments that preserve and transmit cultural knowledge.

A perfect example of my definition of high art is the Oscar-nominated The Secret of Kells. It uses traditional 2-D techniques and is completely accessible – what my critic would call solidly bourgeois middlebrow. Yet it engages and stimulates many levels of thought and emotion at once. You can focus on enjoying individual aspects: the story teaches real history, since it’s based closely on what we know about the journey of the Kells manuscript from Iona; the conflict is not the usual tussle between monochromatic good and bad guys, but instead highlights the struggle between two versions of good (like Miyazaki’s Mononoke Hime – or Sophocles’ Antigone); the nuanced interactions explore the interplay between Paganism and Christianity, myth and history, imagination and discipline, nature and culture; the style incorporates both Celtic curvilinear forms (in the style of the Book of Kells as well as its Jugendstil descendants) and the tense, jagged shapes used in such graphic novels as The Crow or Sin City.

A perfect example of my definition of high art is the Oscar-nominated The Secret of Kells. It uses traditional 2-D techniques and is completely accessible – what my critic would call solidly bourgeois middlebrow. Yet it engages and stimulates many levels of thought and emotion at once. You can focus on enjoying individual aspects: the story teaches real history, since it’s based closely on what we know about the journey of the Kells manuscript from Iona; the conflict is not the usual tussle between monochromatic good and bad guys, but instead highlights the struggle between two versions of good (like Miyazaki’s Mononoke Hime – or Sophocles’ Antigone); the nuanced interactions explore the interplay between Paganism and Christianity, myth and history, imagination and discipline, nature and culture; the style incorporates both Celtic curvilinear forms (in the style of the Book of Kells as well as its Jugendstil descendants) and the tense, jagged shapes used in such graphic novels as The Crow or Sin City.

Put together, the film becomes Gesamtkunstwerk at the level of Wagner’s Nibelungen cycle or Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy: a total, totally absorbing work of art that delights and also exercises the senses, the cortical emotions, the intellect – and achieves this feat without loudly advertising its intent or, for that matter, its artsiness. Unlike the incessant trumpetings about the groundbreaking technique or “socially relevant” content of Avatar, The Secret of Kells came and left quietly. Then again, art of this caliber doesn’t need to shriek for recognition or classification. Its quiet but sure voice is potent enough:

Images and links: kilim rug (Konya, late 19th century); kohiki tokuri sake flask and guinomi sake cup by Kondo Seiko (Niigata, contemporary); poster for Tomm Moore’s The Secret of Kells; Aisling sings magic into Pangur Bán (who has her own lovely story) in The Secret of Kells.

Note: If you visit the comments section, you will find that this review drew the attention of the Kells screenwriter Fabrice Ziolkowski and its US distributor Eric Beckman. Additionally, its principal director, Tomm Moore, linked to the HuffPo version of the review from his blog.

The articles prompted by Avatar:

Avatar: Jar Jar Binks Meets Pocahontas

Lab Rat Cinema: Monetizing the Reptile Brain

Related articles:

Being Part of Everyone’s Furniture: Appropriate Away

The Hyacinth among the Roses: The Minoan Civilization

I love to read your blog.

Neo

I’m glad you’re enjoying it, Neo!

Thanks for sharing this, and the YouTube link of Aisling’s song. 🙂 While I admit I enjoyed Avatar, it was indeed short on subtlety, just as The Secret of Kells comes across as rich with engaging nuances and elements. The fact that it quietly, but effectively speaks for itself underscores its quality as it is with so many forms of art. Excellent post!

Given the sensibility of your own art, Heather, I think you’d really enjoy The Secret of Kells. I believe it will soon be coming out on DVD. I left the “related link” button on the video so that you can see more snippets of it, if you want. An especially beautiful touch in that scene is that Pangur Ban’s shadow is still that of a cat, even though she has been transformed. Pangur Ban, the white cat, is the subject of a celebrated 9th-century poem, written by an Irish monk on the margin of a manuscript from a German monastery. In the movie, they recite it in the original Gaelic over the closing credits.

As for Avatar, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with enjoying it for what it is: impressive eye candy and a feel-good outcome. What’s annoying — because patently untrue — are its claims to uniqueness and/or superiority in any other domain.

Thank you for the kind words and commentary on Kells. Despite the lack of a seven figure marketing budget, The Secret of Kells has not “come and gone” but will continue to play in theaters thoughout the spring and summer. Film will be released to DVD and Blu-ray early October and pre-orders are available on Amazon. For information, trailer, art, etc. check out http://www.kellsmovie.com.

–Eric

Eric, I’m glad someone is doing this. I noticed that you’re also distributing that other unsung delight, Sita Sings the Blues.

Beautiful!

What you call your idiosyncratic definition resonates for me as THE definition of high vs. low art: having to do with “the artist’s attitude towards her/his medium and audience and with the complexity and layering of the artwork’s content, rather than its accessibility.”

The Shakespeare and Dickens examples are telling.

I wonder if I’m a Hellene at heart?

Blessed Be,

Michael

You may well be, Michael — as you can tell from this article, a lot depends on definitions! (smile).

Just want to add my dittos regarding this delightsome post! Very thought-provoking, although I am not adding anything to the discussion! (Not very creative here, sadly!)

I really like the term delightsome — adds layering!

Alas. the (indirect) source for delightsome is terrible, Athena. The Book of Mormon via one of my ever so guilty pleasures, “Jesus’ General”

I thought it was a neologism — play on delightful. Ah well… I guess it shows nothing is totally devoid of value!

Thanks for such a thoughtful analysis. F Ziolkowski (screenwriter)

You’re very welcome, Fabrice — it was an unalloyed pleasure. If you ever need more myths for a screenplay, I’ve got a library ready to go!

Very nice appreciation of “The Secret of Kells.” Especially pleased that you included the “Aisling’s Song” sequence from the film — which, every time I see it, I find very moving. It’s not just the beauty of the song, but the extraordinary transfiguration of the cat — there’s something deeply touching about it. In any case, the whole film is a slam-dunk, and it’s nice to see it getting such articulate appreciation from folks like yourself.

Thank you for the lovely words, Ken! I, too, found that sequence particularly moving. That’s why I chose it. It’s quiet, in all ways minor key, yet immensely powerful. One tiny detail that almost moves me to tears is that as the sprite is making its way down the stairs, its shadow is that of a carefully stepping cat.