Note: this article first appeared as a guest blog post in Scientific American. It got showcased in a few places. Not surprisingly, some were dissatisfied: those who think scientists (especially dark non-Anglo female ones) should be just technicians with no larger contextual views of their work; those who cling to old notions of DNA functions; those enamored of miracle “cures”; and, needless to say, creationists of all stripes.

A week ago, a huge, painstakingly orchestrated PR campaign was timed to coincide with multiple publications of a long-term study by the ENCODE consortium in top-ranking journals. The ENCODE project (EP) is essentially the next stage after the Human Genome Project (HGP). The HGP sequenced all our DNA (actually a mixture of individual genomes); the EP is an attempt to define what all our DNA does by several circumstantial-evidence gathering and analysis techniques.

A week ago, a huge, painstakingly orchestrated PR campaign was timed to coincide with multiple publications of a long-term study by the ENCODE consortium in top-ranking journals. The ENCODE project (EP) is essentially the next stage after the Human Genome Project (HGP). The HGP sequenced all our DNA (actually a mixture of individual genomes); the EP is an attempt to define what all our DNA does by several circumstantial-evidence gathering and analysis techniques.

The EP results purportedly revolutionize our understanding of the genome by “proving” that DNA hitherto labeled junk is in fact functional and this knowledge will enable us to “maintain individual wellbeing” but also miraculously cure intractable diseases like cancer and diabetes.

Unlike the “arsenic bacteria” fiasco, the EP experiments were done carefully and thoroughly. The information unearthed and collated with this research is very useful, if only a foundation; as with the HGP, this cataloguing quest also contributed to development of techniques. What is way off are the claims, both proximal and distal.

A similar kind of “theory of everything” hype surrounded the HGP but in the case of the EP the hype has been ratcheted several fold, partly due to the increased capacity for rapid, saturating online dissemination. And science journalists who should know better (in Science, BBC, NY Times, The Guardian, Discover Magazine) made things worse by conflating junk, non-protein-coding and regulatory DNA.

Biologists – particularly those of us involved in dissecting RNA regulation – have known since the eighties that much of “junk” DNA has functions (to paraphrase Sydney Brenner, junk is not garbage). The EP results don’t alter the current view of the genome, they just provide a basis for further investigation; their definition of “functional” is “biochemically active” – two very different beasts; the functions (let alone any disease cures) will require exhaustive independent authentication of the EP batch results.

Additionally, the findings were embargoed for years to enable the PR blitz – at minimum unseemly when public funds are involved. On the larger canvas, EP signals the increased siphoning of ever-scarcer funds into mega-projects that preempt imaginative, risky work. Last but not least, the PR phrasing choices put wind in the sails of creationists and intelligent design (ID) adherents, by implying that everything in the genome has “a purpose under heaven”.

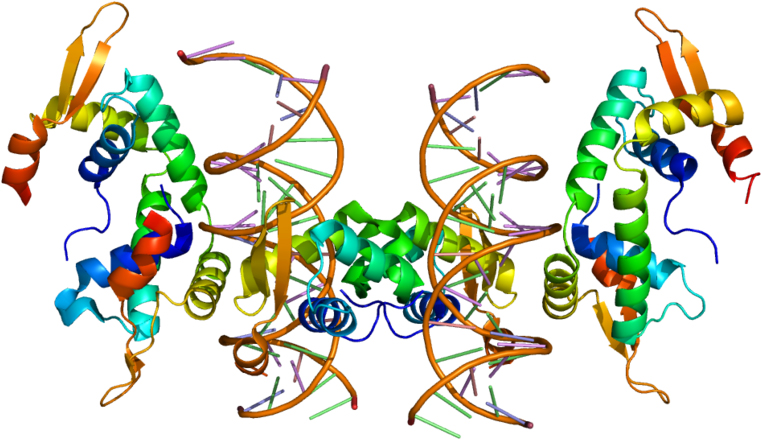

What did the study actually do? The EP consortium labs systematically catalogued such things as DNAase I hypersensitive and methylated sites, transcription factor (TF) binding sites and transcribed regions in many cell types. Unmethylated nuclease-sensitive DNA is in the “open” configuration – aka euchromatin, a state in which DNA can discharge its various roles. The TF sites mean little by themselves: to give you a sense of their predictive power, any synthetically made DNA stretch will contain several such sites. Whether they have a function depends on a whole slew of prerequisites. Ditto the transcripts, of which more anon.

Let’s tackle “junk” DNA first, a term I find as ugly and misleading as the word “slush” for responses to open submission calls. Semantic baggage aside, the label “junk” was traditionally given to DNA segments with no apparent function. Back in the depths of time (well, circa 1970), all DNA that did not code for proteins or proximal regulatory elements (promoters and terminators) was tossed on the “junk” pile.

Let’s tackle “junk” DNA first, a term I find as ugly and misleading as the word “slush” for responses to open submission calls. Semantic baggage aside, the label “junk” was traditionally given to DNA segments with no apparent function. Back in the depths of time (well, circa 1970), all DNA that did not code for proteins or proximal regulatory elements (promoters and terminators) was tossed on the “junk” pile.

However, in the eighties the definition of functional DNA started shifting rapidly, though I suspect it will never reach the 80% used by the EP PR juggernaut. To show you how the definition has drifted, expanded, and had its meaning muddied as a term of art that is useful for everyone besides the workaday splicers et al who are abreast of trendy interpretations that may elude the laity, let’s meander down the genome buffet table.

Protein-coding segments in the genome (called exons, which are interrupted by non-protein-coding segments called introns) account for about 2% of the total. That percentage increases a bit if non-protein-coding but clearly functional RNAs are factored in (structural RNAs: the U family, r- and tRNAs; regulatory miRNAs and their cousins).

About 25 percent of our DNA is regulatory and includes signals for: un/packing DNA into in/active configurations; replication, recombination and meiosis, including telomeres and centromeres; transcription (production of heteronuclear RNAs, which contain both exons and introns); splicing (excision of the introns to turn hnRNAs into mature RNAs, mRNA among them); polyadenylation (adding a homopolymeric tail that can dictate RNA location), export of mature RNA into the cytoplasm; and translation (turning mRNA into protein).

All these processes are regulated in cis (by regulatory motifs in the DNA) and in trans (by RNAs and proteins), which gives you a sense of how complex and layered our peri-genomic functions are. DNA is like a single book that can be read in Russian, Mandarin, Quechua, Maori and Swahili. Some biologists (fortunately, fewer and fewer) still place introns and regions beyond a few thousand nucleotides up/downstream of a gene in the “junk” category, but a good portion is anything but: such regions contain key elements (enhancers and silencers for transcription and splicing) that allow the cell to regulate when and where to express each protein and RNA; they’re also important for local folding that’s crucial for bringing relevant distant elements in correct proximity as well as for timing, since DNA-linked processes are locally processive.

But what of the 70% of the genome that’s left? Well, that’s a bit like an attic that hasn’t been cleaned out since the mansion was built. It contains things that once were useful – and may be useful again in old or new ways – plus gewgaws, broken and rusted items that can still influence the household’s finances and health… as well as mice, squirrels, bats and raccoons. In bio-jargon, the genome is rife with duplicated genes that have mutated into temporary inactivity, pseudogenes, and the related tribe of transposons, repeat elements and integrated viruses. Most are transcribed and then rapidly degraded, processes that do commandeer cellular resources. Some are or may be doing something specific; others act as non-specific factor sinks and probably also buffer the genome against mutational hits. In humans, such elements collectively make up about half of the genome.

So even bona fide junk DNA is not neutral and is still subject to evolutionary scrutiny – but neither does every single element map to a specific function. We know this partly because genome size varies very widely across species whereas the coding capacity is much less variable (the “C-value paradox”), partly because removal of some of these regions does not affect viability in several animal models, including mice. It’s this point that EP almost deliberately obfuscated by trumpeting (or letting be trumpeted) that “junk DNA has been debunked”, ushering in “a view at odds with what biologists have thought for the past three decades.”

Continuing down the litany of claims, will this knowledge help us cure cancer and diabetes? Many diseases are caused not by mutations within the protein-coding regions but by mutations that affect regulation. Unmutated (“wild-type”) proteins at the wrong time, place or amount can and do cause disease: the most obvious paradigm is trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) but cancer and dementia are also prominent members in this category, which includes most of the slow chronic diseases that have proved refractory to “magic bullet” treatments. Techniques that allow identification of changes in regulatory elements obviously feed into this information channel. So a systematic catalogue of regulatory elements across cell types is a prerequisite to homing in on specific stretches known or predicted to have links to a disease or disease susceptibility.

A few potential problems lurk behind this promising front. One is that the variety between normal individual genomes is great – far greater than expected. There’s also the related ground-level question of what constitutes normal: each of us carries a good number of recessive-lethal alleles. So unless we have a robust, multiply overlapping map of acceptable variability, we may end up with false positives – for example, classifying a normal but uncommon variation as harmful. Efforts to create such maps are currently in progress, so this is a matter of time.

Two additional interconnected problems are assigning true biological relevance to a biochemically defined activity and disentangling cause and effect (this problem also bedevils other assays – the related SNP [single nucleotide polymorphism] technique in particular). To say that a particular binding site is occupied in a particular circumstance does not show a way to either diagnostics or therapeutics. “Common sense” deductions from incomplete basic knowledge or forced a priori conclusions have sometimes led to disasters at the stage of application (the amyloid story among them – in which useless vaccines were made based on the mistaken assumption that the plaques are the toxic entities).

The pervasive but clearly erroneous take-home message of “a function for everything” harms biology among laypeople by implying ubiquitous purpose. It also feeds right into the perfectibility concept that fuels such dangerous nonsense as the Genetic Virtue Project. Too, it will attract investors who will push sloppy work based on flimsy foundations. Of course, it’s funny to see creationists fall all over themselves to endorse the EP results while denying the entire foundation that gives raison d’être and context to such projects. As for ID adherents, they should spend some time datamining genome-encompassing results (microarray, SNP, genome-wide associated studies, deep sequencing and the like), to see how noisy and messy our genomes really are. I’d be happy to take volunteers for my microarray results, might as well use the eagerness to do real science!

What the EP results show (though they’re not the first or only ones to do so) is how complex and multiply interlinked even our minutest processes are. Everything discussed in the EP work and in this and many other articles takes place within the cell nucleus, yet the outcomes can make and unmake us. The results also show how much we still need to learn before we can confidently make changes at this level without fear of unpredicted/unpredictable side effects. That’s for the content part. As for the style, it’s true that some level of flamboyance may be necessary to get across to a public increasingly jaded by non-stop eye- and mind-candy.

However, people are perfectly capable of understanding complex concepts and data even if they’re not insider initiates, provided they examine them without wishing to shoehorn them into prior agendas. Accuracy does not equal dullness and eloquence does not equal hype. The EP results are important and will be very useful – but they’re not paradigm shifters or miracle tablets and should not pretend to be.

Citations:

Brenner S (1990). The human genome: the nature of the enterprise (in: Human Genetic Information: Science, Law and Ethics – No. 149: Science, Law and Ethics – Symposium Proceedings (CIBA Foundation Symposia) John Wiley and Sons Ltd.

ENCODE Project Consortium, Bernstein BE, Birney E, Dunham I, Green ED, Gunter C, Snyder M (2012). An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 489:57-74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247.

Stamatoyannopoulos JA (2012). What does our genome encode? Genome Res. 22:1602-11.

Useful Analyses and Critiques:

Birney, E. Response on ENCODE reaction. (Bioinformatician at Large, Sept. 9, 2012).

Note: Ewan Birney is one of the major participants in the ENCODE project.

Eddy, S. Encode says what? (Cryptogenomicon, Sept. 8, 2012).

Eisen M. This 100,000 word post on the ENCODE media bonanza will cure cancer (Michael Eisen’s blog, Sept. 6, 2012).

Timmer, J. Most of what you read was wrong: how press releases rewrote scientific history (Ars Technica, Sept. 10, 2012).

“They’re all gone now, and there isn’t anything more the sea can do to me…. I’ll have no call now to be up crying and praying when the wind breaks from the south //. I’ll have no call now to be going down // in the dark nights after Samhain, and I won’t care what way the sea is when the other women will be keening.”

“They’re all gone now, and there isn’t anything more the sea can do to me…. I’ll have no call now to be up crying and praying when the wind breaks from the south //. I’ll have no call now to be going down // in the dark nights after Samhain, and I won’t care what way the sea is when the other women will be keening.”