If I Forget Thee, O My Grandmother’s Lost Home

Monday, April 27th, 2015Though we smashed their statues,

Though we exiled them from their temples,

That doesn’t mean the gods are dead.

Land of Ionia, it’s you they love still,

It’s you their souls still remember.

— Konstantínos Kaváfis, Ionian

“My two hands here did not do the work, and still they are knotted with it; should not my mind keep the knots as well?”

– Granze in Isak Dinesen’s “The Fish”, Winter’s Tales

[Note: people will have to do their own confirmatory explorations — it’s too painful for me. Also, frustratingly, WordPress won’t render the Turkish diacritics correctly.]

————————————————————————-

All cultures have defining traumas.

For my people, such a trauma is the 1453 fall of Constantinople, the capital of the 1000-year long Byzantine Empire [the current name, Istanbul, comes from the Greek expression “Is tin Pólin” – To the City, with the meaning of which “City” clear]. This ushered an Ottoman occupation of Asia Minor and the Balkans that lasted ~500 years. During that time, non-Turks (which included several Balkan Muslim groups) were by law second-class citizens, subject to religion-specific taxation and penalties, whim deaths and pogroms, and the custom of devshirme (childgathering) to ensure a steady supply of janissaries and odalisques for local beys and the Sultan’s Porte.

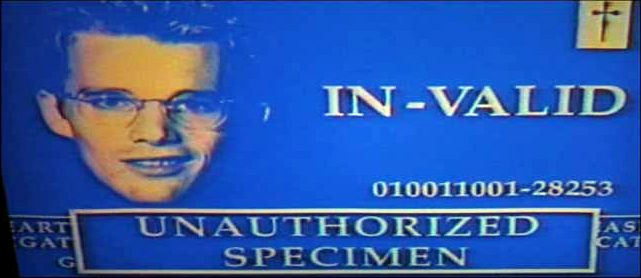

Another trauma is the forcible relocations, massacres and uprootings of the Greeks of Asia Minor (Ionia and Pontus), who had lived there uninterruptedly from about 1500 BCE to 1922 CE, giving rise to the first natural philosophers (Thalís, Anaksímandhros, Irácleitos, Empedhoklís), the song cycles of the Akrítai and just about all the pagan and christian architecture now prominently featured in Turkish tourist brochures. Variants of Yunan (Ionian) is the term for Greek(s) in Turkish, Persian, Armenian, Arabic and Hebrew.

The ethnic cleansing undertaken by the Young Turks to ensure homogeneity was an extreme manifestation of the nationalism that arose after WWI ended several multicultural empires (Ottoman, Austrian-Hungarian, Russian). In nascent Turkey, the Greeks were not alone in their fate. The Armenians of Asia Minor, descendants of the Hittite and Mitanni empires and the kingdom of Urartu, and the Assyrians and Chaldeans of once-mighty Mesopotamia were also systematically dispossessed, forcibly relocated, violated and massacred. The total toll stands at 3.5 million and all Turkish governments (like the Japanese vis-à-vis the Koreans and Chinese) have steadfastly refused to acknowledge these events, placing mention of them under the larger “insult to Turkishness” that can lead to imprisonment or even execution.

For non-Aboriginal Australians and non-Maori New Zealanders, a defining trauma is the casualty-laden and ultimately failed engagement at Gallipoli. WWI claimed 18,000 New Zealanders and 53,000 Australians – for the former, the highest per population combatant toll of that war. However, the Australians were volunteers in their entirety (two conscription referendums were defeated) and conscription was introduced in New Zealand in 1916 — after the Gallipoli finale, when gung-ho war enthusiasm had subsided, depleting enlistment rosters.

The anniversary of the Armenian massacre is April 24. Australia and New Zealand celebrate ANZAC day on April 25. The two dates mesh because the genocide started just before the Gallipoli engagement, to ensure absence of “fifth columnists” within Turkey. There has never been a cinematic depiction of the Asia Minor massacres by a Western director, unlike the countless treatments of equivalent events in WWII Germany and USSR. Peter Weir showed a gritty, if idealized, take of the Gallipoli event through Australian eyes in 1981, with Mel Gibson in his proto-messiah days as protagonist. But all Anglo male stars, it seems, must go through messianic and prophetic phases. Thus we have Russell Crowe’s 2015 The Water Diviner, with its release timed for one of these anniversaries but referring loudly, by both omission and commission, to the other – at least to those familiar with Asia Minor’s tangled history.

The Water Diviner, boasting authenticity because it was filmed in Turkey with official approval, shows an Australian father’s attempt to repatriate the remains of his three sons. Such an unspeakable loss is rich dramatic territory, though the mother is conveniently fridged five minutes in. It is said to be based on a true event, though I wonder if the book source contains as much ugly exoticism and cheap sentimentality as the film. Since Crowe cannot deny himself anything, not only is he near-psychic (he instantly locates a family keepsake in a sea of churned mud) but he also shoehorns in a lightweight romance with a comely, demure and fast-forgiving war widow (augmented with the staple adorable young son) played by Olga Kurylenko, who did much better as the implacable “Pict” scout Etain in Centurion.

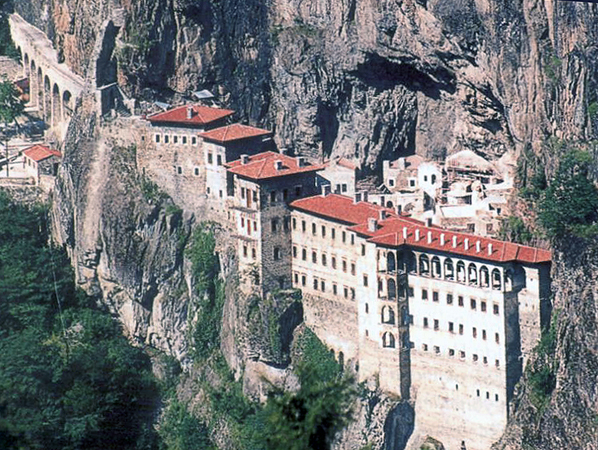

In addition to authenticity of location, The Water Diviner also bruits that it deals “honestly” and “even-handedly” with history. Yet when Crowe’s outback naif Joshua Connor gapes at the Aghía Sofía interior, his guide never mentions the place’s history – though one who knows it can just see the mosaics glimmering through the whitewash. The Armenians are not mentioned even once, and the Greek “soldiers” shown as barbaric invaders in an encounter deep in Anatolia actually wear Pontian ethnic dress (they also speak heavily broken Greek and resemble nothing as much as Peter Jackson’s Southrons). Last but not least, the place where Joshua Connor finds his surviving son (magically turned into a Mevlevi dervish) is Livissi, once a thriving large village and now a graveyard haunted by ghosts.

Perhaps Crowe didn’t know or care. Perhaps this slant was necessary to get his local filming permits. But by trying to honor one trauma (albeit at the price of seeing him in every single frame except the battle flashbacks), he completely and facilely excised or distorted several others. The Australians and New Zealanders of Gallipoli were volunteers fighting a war not on their own soil. The Turks, at least, were fighting on their own ground, and the circumstances that led to the 1922 exchange of populations were not black-and-white. Politics aside, the Armenian, Greek and Assyrian civilians, also in their own long-time homes, were first dispossessed and slaughtered, then erased – for convenience and, in Crowe’s case, for palatable narrative.

There is, however, a film that depicts some of this complexity and does so taking full account of the humanity of all involved. This is Yesim Ustaoglu’s 2003 Waiting for the Clouds – and, unlike Crowe, she braved the Turkish authorities’ displeasure by daring to do so. The main character shares the name Ayshe with the consolation trophy in The Water Diviner (though she has a second, suppressed name) and Waiting for the Clouds also boasts authenticity of location. Thankfully, these are the sole commonalities between the two films.

Waiting for the Clouds is also based on a book, Tamama by Ghiórghos Andhreádhis (by sheer coincidence, my father’s names; Andhreádhis was deported from Turkey because of his books). It unfolds in a Pontian village around 1960, shifting to Thessaloníki for its ending. It interweaves a major and a minor strand that carry all the sorrows of that land. In the stylistic tradition of Angelópoulos, Ustaoglu uses uninterrupted takes, shuns grandstanding and doesn’t explain anything. You have to know history to realize the full impact of what’s being portrayed.

The major strand is of two elderly sisters devoted to each other. The death of one isolates the survivor, Ayshe, who withdraws into herself, spurning her female neighbors’ powerful support network. The connection that still compels her is her love and storytelling for Mehmet, a neighbor’s young son, whose father has “left” – gone to Russia, a common fate for most Balkan and Asia Minor leftists throughout the twentieth century, who routinely faced the choice (if it can be called that) of exile, imprisonment or execution. The minor strand, which acts as a catalyst to the major one, is the return of one of these men – as a leftist Pontian Greek, a triple exile, who returns just to place his hand on what’s left of his family home. [Note: The song that Thanássis sings when he staggers off the boat is famous — a poem by Nobelist Odhysséas Elytis (“The Blood of Love”, part of his Áksion Esti cycle), put to music by Míkis Theodhorákis.]

Ayshe has a faded picture at which she gazes whenever her onerous tasks allow (women in that part of the world double/d as beasts of burden). It slowly emerges that her real name is Eléni, the photo is of her lost family – and Mehmet is an echo of Níkos, her younger brother, who may have managed to reach mainland Greece. The Turkish family of her now-dead sister took her in when she fell behind in one of the death marches of the cleansed and raised her as their own. Nevertheless, the price for her survival was the necessity to suppress her own name, history and language. As a historical note, the Pontian Greeks walked from their Black Sea mountains all the way to Greece, a modern-day repetition of Ksenofón’s Anávassis. They had to leave many behind. Most died; a few had Eléni’s fate.

The return of Thanássis, the exile, sparks Eléni’s desire to find her brother and Thanássis is able to help her locate him. When she allows herself to remember, she speaks in the archaic Greek that is the Pontian dialect – but this is not the sappy, happy reunion that Hollywood would have undoubtedly indulged in. Eléni’s brother is as reluctant to remember as she has been. “Where are you, in all of these?” he asks her, pointing at mountains of family albums of his wife, children, local kin. Eléni silently hands him the single picture that has sustained her – then the film segues into real stills and reels of such families.

Both Waiting for the Clouds and The Water Diviner made me weep, for very different reasons. One embraces all affected, fully acknowledging individual and collective complexities. The other opts for crass erasure dressed in self-righteous veneer. Like Ustaoglu, my mother’s mother hailed from Trebizond; like Eléni, her Greek was accented. Her family had to leave everything behind once and move to Constantinople but as my great-grandfather said, “As long as my children’s head count comes out right, the rest matters not.” Then they had to leave their home in Príngipos, a home they had built from the ground up in their second start – and relocate destitute to Greece, to be called “Tourkósporoi” (Turkish spawn) by local nationalists.

It’s people like my grandmother, and millions like her, that Crowe so callously caricatured and erased. I still can’t summon the strength to investigate if that house in Príngipos still stands, if it still bears the plaque with my grandmother’s last name, Kseniádhis. If I find it, it will probably be as with Thanássis: I, too, will likely place my hand on a ruin. I bear no ill will to whoever inhabits it, if it still stands. But this knowledge will never cease to lacerate my heart, as long as I live.

Images: 1st, the ghostly ruins of Livissi; 2nd, Panaghía Soumelá, the religious center of Pontian Hellenism