Once Again with Feeling: The Planets of Gliese 581

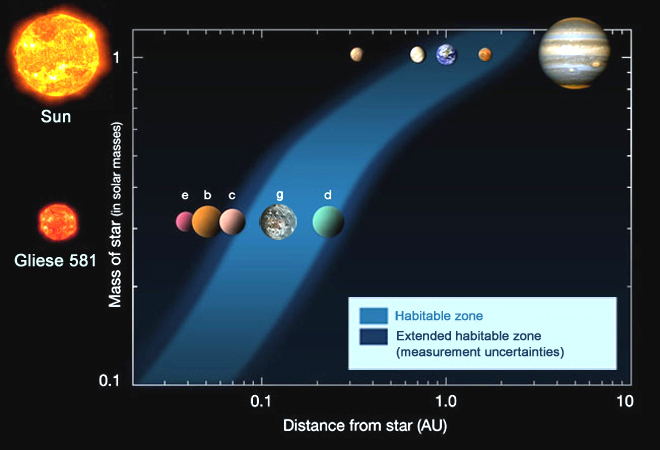

Thursday, September 30th, 2010Gliese 581 may be small as stars go, but it looms huge in the vision field of planetfinders. As of yesterday, measurements indicate the system has six planets of which three are Earth-size and -type, within the star’s habitable zone, with stable, near-circular orbits.

The Gliese 581 system has a persistent will-o-the-wisp quality. Almost each of its planets (c, d, e and now g) has been pronounced in turn to pass the Goldilocks test, only to have expectations shrink when the data get analyzed further. The first frisson of excitement arose when 581c was determined to be Earth-type, which quickened the usual speculations: atmosphere? water? life? We don’t know yet and our current instruments cannot detect biosignatures at that distance (short of an unencrypted request for more Chuck Berry). But there are some things we do know.

Gliese 581 is a red dwarf, a BY Draconis variable. This makes it long-lived; on the minus side, it may produce flares and is known to emit X-rays. Planets in its habitable zone are so close to it that they are tidally locked, always presenting the same face to their star. The temperature differentials resulting from the lock imply hurricane-force winds and tsunami-like tides. Gliese 581g, like 581c, is large enough to retain an atmosphere; the hope is that, unlike 581c or Venus, its specific circumstances have not resulted in a runaway greenhouse effect.

The real paradigm shift is the discovery that this solar system has many earth-size rocky planets, in contrast to the hot-Jupiter/hot-Neptune preponderance in most others. The second enticing attribute of Gliese 581 is its relative closeness — a distance of merely 20 light years. It is still millennia away by our present propulsion systems. But I nurse the dream that if we see anything remotely resembling a biosignature, we will strive to reach it. In the meantime, I suggest we give it a name that fires the imagination. Perhaps Yemanjá, the Yoruba great orisha of the waters, in the hope that the sympathetic magic of the name will work. Perhaps Kokopelli, the trickster piper of the American Southwest cultures, who may entice us thither. I will conclude with the final words of my first article on Gliese 581:

“Whether Gliese 581c [g] is so hospitable that we could live there or so hostile that we could only visit it vicariously through robotic orbiters and rovers, if it harbors life — even bacterial life, often mistakenly labeled “simple” — the impact of such a discovery will exceed that of most other discoveries combined. Unless supremely advanced Kardashev III level aliens seeded the galaxy like the Hainish in Ursula Le Guin’s Ekumen, this life will be an independent genesis, enabling biologists to define which requirements for life are universal and which are parochial.

At this point, we cannot determine if Gliese 581c [g] has an atmosphere, let alone life signatures. If it has non-technological life, without a doubt it will be so different that we may not recognize it. Nor is it a given, despite our fond dreaming in science fiction, that we will be able to communicate with it if it is sentient. In practical terms, a second life sample may exist much closer to home — on Mars, Europa, Titan or Enceladus. But those who are enthusiastic about this discovery articulate something beyond its potential seismic impact on biology and culture: the desire of humanity for companions among the sea of stars, a potent myth and an equally potent engine for exploration.”

At this point, we cannot determine if Gliese 581c [g] has an atmosphere, let alone life signatures. If it has non-technological life, without a doubt it will be so different that we may not recognize it. Nor is it a given, despite our fond dreaming in science fiction, that we will be able to communicate with it if it is sentient. In practical terms, a second life sample may exist much closer to home — on Mars, Europa, Titan or Enceladus. But those who are enthusiastic about this discovery articulate something beyond its potential seismic impact on biology and culture: the desire of humanity for companions among the sea of stars, a potent myth and an equally potent engine for exploration.”

Images: Top, comparison of the Sun and Gliese 581 habitable zones (the diagram is by Franck Selsis, Univ. of Bordeaux; the image of 581g was originally created for 581c by Ginny Keller); bottom, Kokopelli playing his flute.

Note: This article has been reprinted on Huffington Post.