A Plague on Both Your Houses – Reprise

Saturday, May 28th, 2011Note: This article originally appeared in the Apex blog, with different images. The site got hacked since then and its owner did not feel up to reconstituting the past database. I reprint it as a companion piece to Sam Kelly’s Privilege and Fantasy.

Don’t you know

Don’t you know

They’re talkin’ ’bout a revolution

– Tracy Chapman

In James Tiptree’s “Houston, Houston, Do You Read?” three male astronauts are thrown forward in time and return to an earth in which an epidemic has led to the extinction of men. They perceive a society that needs firm (male) guidance to restore correct order and linear progress. In fact, the society is a benevolent non-coercive non-hierarchical anarchy with adequate and stable resources; genetic engineering and cloning are advanced, spaceships are a given, there’s an inhabited Lunar base and multiple successful expeditions to Venus and Mars. One of the men plans to bring the women back under god’s command (with him as proxy) by applying Pauline precepts. Another plans to rut endlessly in a different kind of paradise. The women, after giving them a long rope, decide they won’t resurrect the XY genotype.

The skirmish in the ongoing war about contemporary fantasy between Leo Grin and Joe Abercrombie reminds me of Tiptree’s story. Grin and Abercrombie argued over fantasy as art, social construct and moral fable totally oblivious to the relevant achievements of half of humanity – closer to ninety percent, actually, when you take into account the settings of the works they discussed. No non-male non-white non-Anglosaxon fantasy writers were mentioned in their exchanges and in almost all of the reactions to their posts (I found only two partial exceptions).

I expected this from Grin. After all, he wrote his essay under the auspices of Teabagger falsehood-as-fact generator Andrew Breitbart. His “argument” can be distilled to “The debasement of heroic fantasy is a plot of college-educated liberals!” On the other hand, Abercrombie’s “liberalism” reminds me of the sixties free-love dictum that said “Women can assume all positions as long as they’re prone.” The Grin camp (henceforth Fathers) conflates morality with religiosity and hearkens nostalgically back to Tolkien who essentially retold Christian and Norse myths, even if he did it well. The Abercrombie camp (henceforth Sons) equates grittiness with grottiness and channels Howard – incidentally, a basic error by Grin who put Tolkien and Howard in the same category in his haste to shoehorn all of today’s fantasy into the “decadent” slot. In fact, Abercrombie et al. are Howard’s direct intellectual descendants, although Grin’s two idols were equally reactionary in class-specific ways. Fathers and Sons are nevertheless united in celebrating “manly” men along the lines demarcated by Tiptree.

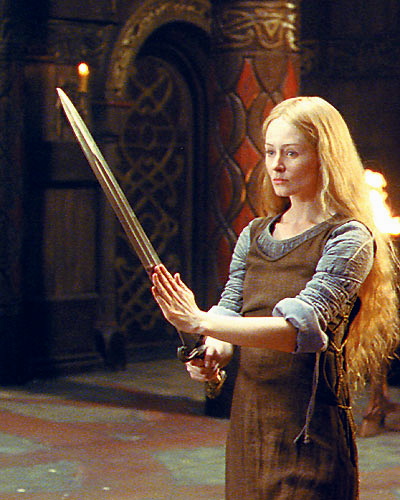

As I’ve said elsewhere, I enjoy playing RPGs in many guises. But even for games – let alone for reading – I prefer constructs that are nuanced and, equally importantly, worlds in which I can see myself living and working. Both camps write stories set in medieval worlds whose protagonists are essentially Anglosaxon white men with a soupçon of Norse or Celt to spice the bland gruel. To name just a few examples, this is true of Tolkien’s Middle Earth, Howard’s Conan stories, Moorcock’s Elric saga, Leiber’s Fafhrd series, Jordan’s Wheel of Time toe-bruisers, Martin’s fast-diminishing-returns Fire and Ice cycle. The sole difference is approach, which gets mistaken for outlook. If I may use po-mo terms, the Fathers represent constipation, the Sons diarrhea; Fathers the sacred, Sons the profane – in strictly masculinist terms. In either universe, women are deemed polluting (that is, distracting from bromances) or furniture items. The fact that even male directors of crowd-pleasers have managed to create powerful female heroes, from Jackson’s Éowyn to Xena (let alone the women in wuxia films), highlight the tame and regressive nature of “daring” male-written fantasy.

Under the cover of high-mindedness, the Fathers posit that worthy fantasy must obey the principles of abrahamic religions: a rigid, stratified society where everyone knows their place, the color of one’s skin determines degree of goodness, governments are autocratic and there is a Manichean division between good and evil: the way of the dog, a pyramidal construct where only alpha males fare well and are considered fully human. The Sons, under the cover of subversive (if only!) deconstruction, posit worlds that embody the principles of a specific subset of pagan religions: a society permanently riven by discord and random cruelty but whose value determinants still come from hierarchical thinking of the feudal variety: the way of the baboon, another (repeat after me) pyramidal construct where only alpha males fare well and are considered fully human. Both follow Campbell’s impoverished, pseudo-erudite concepts of the hero’s quest: the former group accepts them, the latter rejects them but only as the younger son who wants the perks of the first-born. Both think squarely within a very narrow box.

Other participants in this debate already pointed out that Tolkien is a pessimist and Howard a nihilist, that outstanding earlier writers wrote amoral works (Dunsany was mentioned; I’d add Peake and Donaldson) and that the myths which form the base of most fantasy are riddled with grisly violence. In other words, it looks like Grin at least hasn’t read many primary sources and both his knowledge and his logic are terminally fuzzy, as are those of his supporters.

A prominent example was the accusation from one of Grin’s acolytes that contemporary fantasy is obsessed with balance which is “foreign to the Western temperament” (instead of, you know, ever thrusting forward). He explicitly conflated Western civilization with European Christendom, which should automatically disqualify him from serious consideration. Nevertheless, I will point out that pagan Hellenism is as much a cornerstone of Western civilization as Christianity, and Hellenes prized balance. The concept of “Midhén ághan” (nothing in excess) was crucial in Hellenes’ self-definition: they watered their wine, ate abstemiously, deemed body and mind equally important and considered unbridled appetites and passions detriments to living the examined life. At the same time, they did not consider themselves sinful and imperfect in the Christian sense, although Hellenic myths carry strong strains of defiance (Prometheus) and melancholy (their afterworld, for one).

Frankly, the Grin-Abercrombie fracas reminds me of a scene in Willow. At the climax of the film, while the men are hacking at each other down at the courtyard, the women are up at the tower hurling thunderbolts. By the time the men come into the castle, the battle has been waged and won by women’s magic.

So enough already about Fathers and Sons in their temples and potties. Let’s spend our time more usefully and pleasantly discussing the third member of the trinity. Before she got neutered, her name was Sophia (Wisdom) or Shekinah (Presence). Let’s celebrate some people who truly changed fantasy – to its everlasting gain, as is the case with SF.

My list will be very partial and restricted to authors writing in English and whose works I’ve read, which shows we are dealing with an embarrassment of riches. I can think of countless women who have written paradigm-shifting heroic fantasy, starting with Emily Brontë who wrote about a world of women heroes in those tiny hand-sewn diaries. Then came trailblazers Catherine Moore, Mary Stewart and André Norton. Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea is another gamechanger (although her gender-specific magic is problematic, as I discussed in Crossed Genres) and so is her ongoing Western Shores series. Katherine Kurtz’s Deryni cycle is as fine a medieval magic saga as any. We have weavers of new myths: Jane Yolen, Patricia McKillip, Meredith Ann Pierce, Alma Alexander; and tellers of old myths from fresh perspectives: Tanith Lee, Diana Paxson, Marion Zimmer Bradley, Terri Windling, Emma Bull, C. J. Cherryh, Christine Lucas.

Then there’s Elizabeth Lynn, with her Chronicles of Tornor and riveting Ryoka stories. Marie Jakober, whose Even the Stones have haunted me ever since I read it. Elizabeth Marshall Thomas, whose heroic prehistoric fantasies have never been bested. Jacqueline Carey, who re-imagined the Renaissance from Eire to Nubia and made a courtesan into a swashbuckler in the first Kushiel trilogy, showing a truly pagan universe in the bargain. This without getting into genre-cracking mythmakers like Isak Dinesen (Karen Blixen) and Louise Erdrich.

These authors share several attributes: they have formidable writing skills and honor their sources even as they transmute them. Most importantly, they break the tired old tropes and conventional boundaries of heroic fantasy and unveil truly new vistas. They venture past medieval settings, hierarchical societies, monotheistic religions, rigid moralities, “edgy” gore, Tin John chest beatings, and show us how rich and exciting fantasy can become when it stops being timid and recycling stale recipes. As one of the women in Tiptree’s “Houston, Houston” says: “We sing a lot. Adventure songs, work songs, mothering songs, mood songs, trouble songs, joke songs, love songs – everything.”

Everything.

Images: Éowyn, shieldmaiden of Rohan (Miranda Otto) in The Two Towers; Sonja, vampire paladin (Rhona Mitra) in Rise of the Lycans; Yu Shu Lien, Wudan warrior (Michelle Yeoh) in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon.