Superficial Darkness and Luminous Ink

Friday, March 29th, 2013 There has been a resurgence of arguments over grimdark fantasy, sparked by Joe Abercrombie’s recent second salvo after his earlier pas-de-deux with Leo Grin. This time around, Abercrombie equated “realism” (as in: non-stop pillage and teen-level gothness… or is it kvothness?) with “honesty” while arguing with a semi-straight face that he, unlike those who dislike gratuitous grottiness, was not making moral judgments.

There has been a resurgence of arguments over grimdark fantasy, sparked by Joe Abercrombie’s recent second salvo after his earlier pas-de-deux with Leo Grin. This time around, Abercrombie equated “realism” (as in: non-stop pillage and teen-level gothness… or is it kvothness?) with “honesty” while arguing with a semi-straight face that he, unlike those who dislike gratuitous grottiness, was not making moral judgments.

Last time around, I was the sole non-anglomale to enter this fray. This time, several women responded (links below). All raised important issues (the exclusive focus on rape of women; the determined distortion/impoverishment of real history; the fact that several items are subsumed under “grittiness”), though Elizabeth Bear’s defense of (revisionist) grimdark bears this immortal phrase: “…sociopathic monsters can and do accomplish good – sometimes purposefully, sometimes not.” In other words, a soldier who participated in flattening a village is a force for good because he let one of the village children survive.

Having said my piece on grittygrotty fantasy, I don’t deem the subgenre interesting enough for additional investment. However, during these discussions journalist and author Sabrina Vourvoulias wondered if Ink, her debut novel, is classifiable as grimdark because it contains some of the items that are de rigueur in that domain: betrayal by friends; death of beloved and/or central characters; violence and violations; grim settings and unhappy endings. I had long intended to write a review of Ink, so I considered this my opportunity.

My verdict: Ink is not grimdark if only because it’s not the standard-issue SFF watery gruel. It’s also not grimdark because: it spends as much time showing beauty, heroism and honor as squalor, betrayal and violence; its violence (except in one instance) is neither gratuitous nor meant to titillate; it shows imperfect but functioning individuals, families and communities, not the baboon troops standard in grimdark; it doesn’t fridge its women (instead, it hews to the more traditional mode of “men die, women endure”); it shows mutual desire and consensual sex with neither prudery nor prurience; it’s layered and nuanced; and it’s politically engaged and grounded in reality while also containing doors ajar to other worlds.

Some reviewers compared Ink to Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, because both show near-future US societies based on plausible extrapolations. But whereas The Handmaid’s Tale is straight dystopia, Ink is more than that. Ink is a nagual, like one of its protagonists: a twinned being, a shapeshifter – something common in non-Anglo literature that has left its genre boundaries porous instead of having them patrolled by purity squads. Ink combines mythic, epic, dystopian, urban and paranormal fantasy – it’s a direct descendant of the better-known Hispanophone magic realists. Its closest contemporary relatives are Evghenía Fakínou’s luminous works, famous in Hellás but unknown to Anglophone readers.

Ink describes a very near-future US in which the distinction between full citizens and the rest has become absolute and is enforced by biometric tattoos that specify status. Those who are not full citizens are subject to the customary abuses: curfews, job and housing discrimination, deportations, concentration camps, child abductions, involuntary sterilizations, vigilante violence. The story, spread over a decade, chronicles the reactions to this setting in both the real and magical realms.

The real echoes are multiple: there have been many near-silent holocausts in Latin America during caudillo regimes; biometric identification and surveillance methods are already with us; the treatment of “aliens” has been an endemic festering wound in many polities, the US prominently among them; tattoos and concentration camps have been used throughout history to isolate “others”; and “others” are routinely dehumanized across times and cultures – usually as a means of retaining power (for the strong), borderline privileges and self-esteem (for the weak), as well as an easy method for retaining social homogeneity.

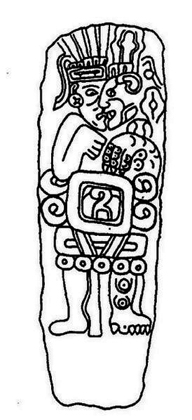

The magical echoes are subtler but just as layered: the naguales come from age-old shamanistic practices in Mesoamerica; the belief in magic linked to a specific location is ancient and universal; so are the concepts of shadow doubles and wereanimals, both good and evil. There are liaisons between the two realms – not only the half-dozen primary and secondary characters with second sight and/or twinned selves, but also the kaibiles, who appear as fearsome adversaries in dreamtime within Ink but in realtime were the infamous Guatemalan counter-insurgency special forces.

The magical echoes are subtler but just as layered: the naguales come from age-old shamanistic practices in Mesoamerica; the belief in magic linked to a specific location is ancient and universal; so are the concepts of shadow doubles and wereanimals, both good and evil. There are liaisons between the two realms – not only the half-dozen primary and secondary characters with second sight and/or twinned selves, but also the kaibiles, who appear as fearsome adversaries in dreamtime within Ink but in realtime were the infamous Guatemalan counter-insurgency special forces.

There are no “alpha” heroes in Ink; those of its characters who achieve heroic status do so without fanfare by simply being decent and taking risks despite fear and consequences – and while embedded in complex networks of blood and chosen relatives (the sole glaring absence is that of old women). The characters are economically but sharply delineated and their intertwinings are natural and believable. Where Ink approaches quotidian is in the choices of its protagonists’ occupations: Finn, a journalist; Mari, a liaison/translator; Del, a painter; Abbie, a computer wunderkind.

Ink also stumbles slightly by giving its two women protagonists remarkably similar fates. Both get violated – Mari by a decent-appearing vigilante, Abbie by a once-dear friend. The latter is the only point where Ink is in danger of entering generic grimdark territory: not only is Abbie’s sadistic scarring not really necessary to the plot, but it’s also totally out of character for the person who inflicted it. Also, both women have to carry on after the loss of the loves of their lives, with children as their main consolation prize (though they also reclaim other vital pieces of themselves that make them more than just custodians of the future).

Two secondary characters cast enormous shadows in Ink and almost walk away with the novel – I for one would happily read tomes centered on each: Toño, a gang leader with the charisma and code of honor that often goes with such positions; and Meche, who walks between worlds like Mari – and is also a formidable chemist, the inventor of synthetic skin that can give passage to legitimacy. [Note to self: the successor to The Other Half of the Sky will focus on women scientists; tap Sabrina for a Meche story.]

Stylistically, Ink commits all the “errors” excoriated in HackSFFWorkshop 101, though (repeat after me) they’re common in literary fiction and I personally love them: its four protagonists speak in first person and often in present tense; it makes unapologetic jumps in narrative time; it has an enormous cast of characters, without obvious telegraphings of who’s important and who isn’t; and its chapters have titles instead of numbers.

The language in Ink clearly comes from someone who is a fluent speaker of more than one tongue: it has the giveaway shimmer of submerged harmonies, of unexpected, felicitous word couplings. Ink also has snappy dialogue and vivid descriptions. Some exchanges made me laugh out loud or weep a little, and the erotic passages pack real heat. The peripheral characters are sharply drawn and distinct, and the Latinos are not generic. They’re Mexicans, Cubans, Guatemalans, with their unique histories, customs, dialects and magicks.

Some reviewers complained that the paranormal element in Ink was intrusive or not well integrated. I’d argue that the real problem is that Ink should be much longer than it is. Although it’s a saga of sorts, it has a strobe-light staccato effect that fits its current lean frame. But unlike just about any other SFF book I’ve read recently (nearly all infected with the dreaded sequelitis virus), the issues and characters in Ink – as well as its author’s talent for weaving richly-hued tapestries – cry out for a Márquez-size door stopper.

If Ink had been written in any language but English, it would have become a bestseller with reviews in the equivalent of the NY Times. For Anglophones, Ink is an uncategorizable hybrid. These terms are invariably used to signify that a book is doomed because it doesn’t aim for an automatically defined readership. I, however, a walker between worlds myself, use the terms as rare praise.

If Ink had been written in any language but English, it would have become a bestseller with reviews in the equivalent of the NY Times. For Anglophones, Ink is an uncategorizable hybrid. These terms are invariably used to signify that a book is doomed because it doesn’t aim for an automatically defined readership. I, however, a walker between worlds myself, use the terms as rare praise.

Images: 1st, Ink (publisher: Crossed Genres); 2nd, a jaguar nagual (sketch from a Zapotec stela by Javier Urcid); 3rd, Sabrina Vourvoulias

Links to recent discussions of grittygrotty fantasy:

Foz Meadows

Sophia McDougall

Liz Bourke

Marie Brennan

Elizabeth Bear