The Poison Tree

Tuesday, August 22nd, 2017 A recent article by David Futrelle (of We Hunted the Mammoth fame) contains this long-known fact: “There are good reasons why MRA activism has served for so many as a gateway drug to the alt-right.” Major props to Mr. Futrelle for his long-standing public stance, though many had said this before him. But, of course, he is in the right demographic groups to be instantly heeded and signal-boosted.

A recent article by David Futrelle (of We Hunted the Mammoth fame) contains this long-known fact: “There are good reasons why MRA activism has served for so many as a gateway drug to the alt-right.” Major props to Mr. Futrelle for his long-standing public stance, though many had said this before him. But, of course, he is in the right demographic groups to be instantly heeded and signal-boosted.

Gamergaters, MRAs, Tarzanist evopsychos, White supremacists, coercive fundies — and even minor knobs like Google’s Damore — are fruits of a single poison tree. They’re all part of a single mindset configuration: the urge to dominate, the concept of automatic entitlement, the unhesitating use of corrosive dicta as untouchable “truths”. Just about all of humanity’s tragedies stem from this. As one character in Brendan Muldowney’s ferocious Pilgrimage says, “Peace needs to be grown, cared for, nurtured. This is beyond the reach of most men.”

Damore’s “manifesto” (a whiny, stale recycling of disproved masculinist platitudes) has been thoroughly debunked by many experts, including evolutionary biologist Suzanne Sadedin PhD who has written several justly famous essays about the species-unique problems of human pregnancy and menstruation. But I want to discuss Pilgrimage a bit more, because it gives a pared-down glimpse of the poison tree.

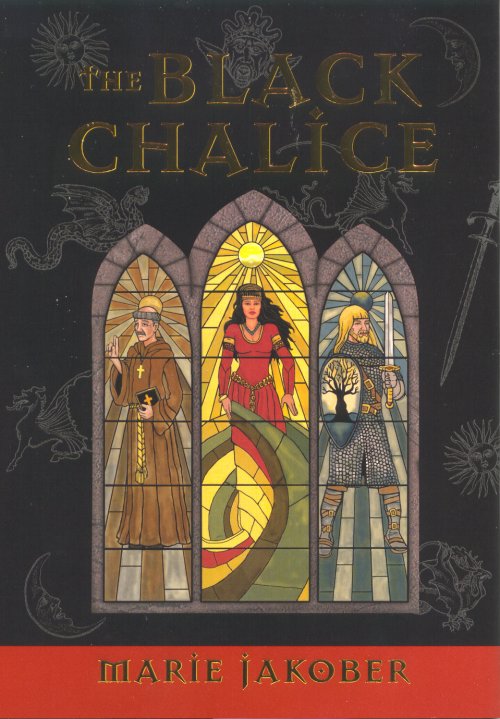

At first glance, Pilgrimage is a perilous mission in hostile territory, equal parts Secret of Kells and Wages of Fear with a Fellowship of the Ring soupçon. Its portrayal of ambition, delusion and obsession passing for piety and loyalty makes it sibling to Marie Jakober’s riveting Black Chalice that also takes place during the cusp between paganism and full-bore monotheism. Pilgrimage unfolds in 13th century Ireland just after the Fourth Crusade, whose most prominent achievement was the destruction of Byzantium. The nucleus is a group of monks who are ordered to transport their monastery’s holiest relic to Rome.

Like all relics of this type, theirs is a combination of bizarre and gruesome: it’s said to be the rock that delivered the killing blow during the stoning of the apostle chosen to replace Judas. And, as is gradually revealed, it’s also “metal from heaven” – highly conducting meteoritic iron, which endows it with the ability to deliver shocks. Somehow, it found its way to an isolated Irish monastic community. The Pope has caught wind of it and plans to use it to separate the “worthy faithful” from the rest of the herd. As his domini canus he has sent a Cistercian who has bartered his soul to the father god by denouncing his own father as tolerant of heretics (this was an era of significant “cleansings”).

But there are others who want the rock for reasons essentially identical to the Pope’s (once the pious veneer is stripped from the orotund proclamations). Among them are Irish clans fallen into savagery after they’ve been deprived of their land and social structures; and Norman petty-noble mercenaries who have been laying waste to Eire ever since they were invited to help settle one of the perennial wars between Irish kings – an invasion authorized and blessed by the Pope, as was the sacking of Constantinople: both Irish and Greek Christianity were competitors to be annihilated.

Several recognizable character types inhabit Pilgrimage: the naïve innocent (shades of Adso from The Name of the Rose), the wise humane mentor, the atoning sinner with an unbreakable geas…and embodiments of two seemingly different kinds of ruthlessness, secular and religious, that are in fact just different ways of vying for the same trophy: the might that makes everything right.

The film boasts stunning scenery as well as gut-churning violence, and builds verisimilitude by showing seaweed harvesting, beehive cells and Culdee tonsures; and by using Gaelic and French when it should. Several reviewers called it cynical (though the correct term would have been nihilistic) because it refuses to make concessions to sentimentality: it denies any glimpse of hope or real redemption – signaled in part by a body count rivaling a Jacobean play, but even more so by the total absence of women.

The film has reduced the depiction of the poison tree to its primal colors: the will to power, the urge (and perceived right) to destroy whatever stands in the “correct” way. Whether one screams “Deus le Vult” or “Allahu Akbar”, whether one invokes sacred heritage or divine laws to justify cruelty – it’s the same poison tree that bears this strange fruit, that keeps sprouting like a toxic weed, like dragons’ teeth, in even carefully tended gardens. Only vigilant, determined decency will keep it from strangling all around it.

In-Depth Review of Pilgrimage at Paste Magazine

Related Essays

The Hyacinth among the Roses: The Minoan Civilization

Is It Something in the Water? Or: Me Tarzan, You Ape

The Andreadis Unibrow Theory of Art

A Plague on Both Your Houses – Reprise

Who Will Be Companions to Female Kings?

That Shy, Elusive Rape Particle

Free Speech: Bravehearts and Scumbags

So, Where Are the Outstanding Women in X?

Images: Top, original cover of Marie Jakober’s Black Chalice; bottom, beehive cells on Skellig island