“There are two novels that can change a bookish fourteen-year old’s life: The Lord of the Rings and Atlas Shrugged. One is a childish fantasy that often engenders a lifelong obsession with its unbelievable heroes, leading to an emotionally stunted, socially crippled adulthood, unable to deal with the real world. The other, of course, involves orcs.” — John Rogers, Ephemera 2009

From time to time items appear in news or social media that remind me I’ve long wanted to discuss Ayn Rand. The latest is the Sad Puppies’ Hugo awards campaign, whose leaders announced that next time the charge of the Lightweight Brigade will be led by women who are not like the rest of us unworthy hysterics. Prominent among the vessels chosen to carry the yellowish fluid of “pure” SF is one who parrots Ayn Rand. In this era of voided social contracts and vanishing safety nets, several of the current Republican presidential candidates name themselves Rand adherents – except that the coin she minted has proved counterfeit not only for societies, but also for the individuals she purported to champion.

Born Alyssa Rosenbaum to a middle-class Russian-Jewish family, multiply displaced by Soviet policies, possessing immense drive and the type of intelligence that made her a poor fit to any homogeneous group ruled by implicit traditions, Rand managed to emigrate to the US. Once there, she strove – with enormous success – to reinvent herself far beyond the usual name change and veneer assimilation of zero- and first-generation immigrants. She also attempted to reshape, Procrustes-like, all within her reach to fit her fantasy of perfection, including her personal past, her hapless low-key husband and eventually her acolytes.

Countless critics have dissected Rand’s juvenile “philosophy” (who seriously lists Aristotle as a decisive influence?), cartoonish characters and clunky dialogue, humorless didacticism, worship of Aryan-phenotype übermenschen and their Nietzschean prerogatives, cult-leader behavior. Equally countless admirers have cleaved to Rand’s powerful message of purpose and self-esteem, which she eventually distorted into suffocating diktats. Less discussed is a fundamental contradiction: despite her trumpetings that she stood solitary and independent as a sui generis entirely self-made construct, Rand not only had far more help than she acknowledged, but she also abjectly desired to belong to clubs perceived to occupy the top of intellectual and/or political hierarchies. This is common for many with backstories similar to Rand’s: Dinesh D’Souza, Cathy Young (Ekaterina Jung), Piyush “Bobby” Jindal, Camille Paglia, Marco Rubio, Sarah Hoyt (Alice Maria da Silva Marques de Almeida), Martin Shkreli.

Rand and the others I listed decided that the path to first-class citizenship in their adoptive US culture was to become mouthpieces for its most reactionary substreams. They’re born-again Spencerians, staunch promoters of libertarian bootstrapping myths, and as obsessed with purge-enforced purity as their ideological opponents. However, their intrinsics mean they can never be more than court jesters or spear carriers of the masters they choose; they end up becoming collaborators, cudgels against fellow disadvantaged who are trying different ways of becoming acknowledged as fully human. For the women, it additionally means they invariably become more kyriarchal than MRAs, since they must be be seen as different than the rest of their weak-minded hormone-driven gender. Before I go further, I want to make it clear that I regard both extreme identity politics and total isolationism (that is, complete refusal to interact with one’s adoptive culuture) as dysfunctional and sterile as the appeasing mimic mode that I discuss here.

Ayn Rand is a beguiling beacon for bright, self-motivated social isolates who have no obvious tribe and decide to make a defiant virtue of aloneness. When I was fourteen and a student in one of Greece’s elite exam-entry schools during the junta, one of my teachers handed me The Fountainhead remarking it had been written with me in mind. On the surface, I was the ideal audience for its message: an overachieving loner proud of her otherness, neither feminine nor pretty; a fledgling contrarian who disliked unexamined majority views and was already being treated as “an honorary man”; the member of a family chronically persecuted for its political beliefs and actions; a believer in principles, meritocracy and perfectibility like most adolescents.

Ayn Rand is a beguiling beacon for bright, self-motivated social isolates who have no obvious tribe and decide to make a defiant virtue of aloneness. When I was fourteen and a student in one of Greece’s elite exam-entry schools during the junta, one of my teachers handed me The Fountainhead remarking it had been written with me in mind. On the surface, I was the ideal audience for its message: an overachieving loner proud of her otherness, neither feminine nor pretty; a fledgling contrarian who disliked unexamined majority views and was already being treated as “an honorary man”; the member of a family chronically persecuted for its political beliefs and actions; a believer in principles, meritocracy and perfectibility like most adolescents.

For reasons partly mentioned in Snachismo, I left my native culture for the world-dominant US polity. Though I’m not “of color” (unless it becomes convenient to someone’s agenda) as defined by the crudely reductive US criteria, I’m one of the borderline ethnics designated as “sneaky swarthons” across Anglosaxon cultures. If you believe this is no longer applicable, re-read the presentations of the recent Greek economic debacle in European media. I came to the US younger than Rand and without any family whatsoever; she, despite her later disavowals, lived with her first-degree relatives until she went to California using their money. What I had instead was a full scholarship and the buffers a well-endowed university could provide.

As I continued living in the US, I kept piling up all kinds of credentials and accomplishments. Nevertheless, I was still olive-skinned and still had an unpronounceable name and a legacy accent – with the result that I was often treated as mud (or worse) on a shoe. I later found out that I shared all these attributes and equivalent experiences with Rand herself. By all counts, I should have become a fervent lifelong Objectivist.

What saved me from such a fate? Perhaps that I had an empathy organ, which Rand (like other transmit-only narcissists) notoriously lacked. Or that I never repudiated my heritage, warts and all – even as I selectively chose what to retain from it, and what to adopt from the more cosmopolitan milieus I found myself in. Or that unlike Rand’s proud announcement that she was “a male chauvinist”, I was a feminist even before I knew the term (or movement) existed. Or that I wanted to become a scientist from the moment I could think clearly, and during my training for that vocation it got pressed into me with diamond-tipped drills that theories must fit facts, not the other way around. Or that I could never identify with Rand’s Aryan blonds, modeled on those who had tortured and exterminated my people and other “inferiors” like vermin. Or that the thought of becoming someone’s Joan the Baptist or Mary Magdalene, no matter how remarkable they might be, made me break into hives.

Yet I was still fascinated by the “there but for fortune go I” aspect. So after The Fountainhead I went on to read Atlas Shrugged, We the Living, and the Barbara Branden and Ann Heller biographies. And so I found out the desolation and insoluble conflicts behind Rand’s bravado. Like many of that personality type, her strengths gave her a strong sense of entitlement that she assumed should, and would, automatically translate to privilege. People far less intelligent than Rand rose to prominence through membership in a dominant group, so it was not surprising she felt short-changed. Deprived of the desired recognition from the alpha club (loner pretensions notwithstanding), she ended up becoming the “there can only be one” tai-tai of designated lesser beings: like her, all her inner circle were smart, ambitious Jews in a society that still imposed racial and ethnic group segregations and quotas. She considered her followers, and they considered themselves, second-best – especially the women whom she turned into typists and gofers. This resulted in shattered, stunted lives. And like all people in this no-win position, anger and depression stalked Rand throughout her life.

I know this anger only too well. I have to keep a tight rein on it, lest it consume me. I’ve come to realize that the siren call of self-made climbing is meant to keep people like me trying solo for brass rings: box-ticking tokens at best. But unlike Rand, I figured this out early enough to choose a different path. This won’t make me beloved, influential, famous or rich. But neither will it make me mutilate my feet to fit stiletto-heeled glass slippers. For exiled wanderers like me, perhaps the only viable option is to keep our double vision intact and acknowledge the value of uncoerced cooperation and shared visions, even as we recognize that all alliances are fleeting. We will always sail on half-familiar seas, Flying Hollanders with the albatross of loneliness around our necks. Even so, we can try to become links between our natal and adopted cultures, branches tapping on windows, gravity ripples between stars.

I know this anger only too well. I have to keep a tight rein on it, lest it consume me. I’ve come to realize that the siren call of self-made climbing is meant to keep people like me trying solo for brass rings: box-ticking tokens at best. But unlike Rand, I figured this out early enough to choose a different path. This won’t make me beloved, influential, famous or rich. But neither will it make me mutilate my feet to fit stiletto-heeled glass slippers. For exiled wanderers like me, perhaps the only viable option is to keep our double vision intact and acknowledge the value of uncoerced cooperation and shared visions, even as we recognize that all alliances are fleeting. We will always sail on half-familiar seas, Flying Hollanders with the albatross of loneliness around our necks. Even so, we can try to become links between our natal and adopted cultures, branches tapping on windows, gravity ripples between stars.

Related Essays

And Ain’t I a Human?

Snachismo, or: What Do Women Want?

Is It Something in the Water? Or: Me Tarzan, You Ape

Only Kowtowers Need Apply

“As Weak as Women’s Magic”

A Plague on Both Your Houses

Who Will Be Companions to Female Kings?

Caesars and Caesar Salads

History, Legitimacy and Belonging; or: Who’s We, Kemo Sabe?

The Smurfettes Discover Ayn Rand

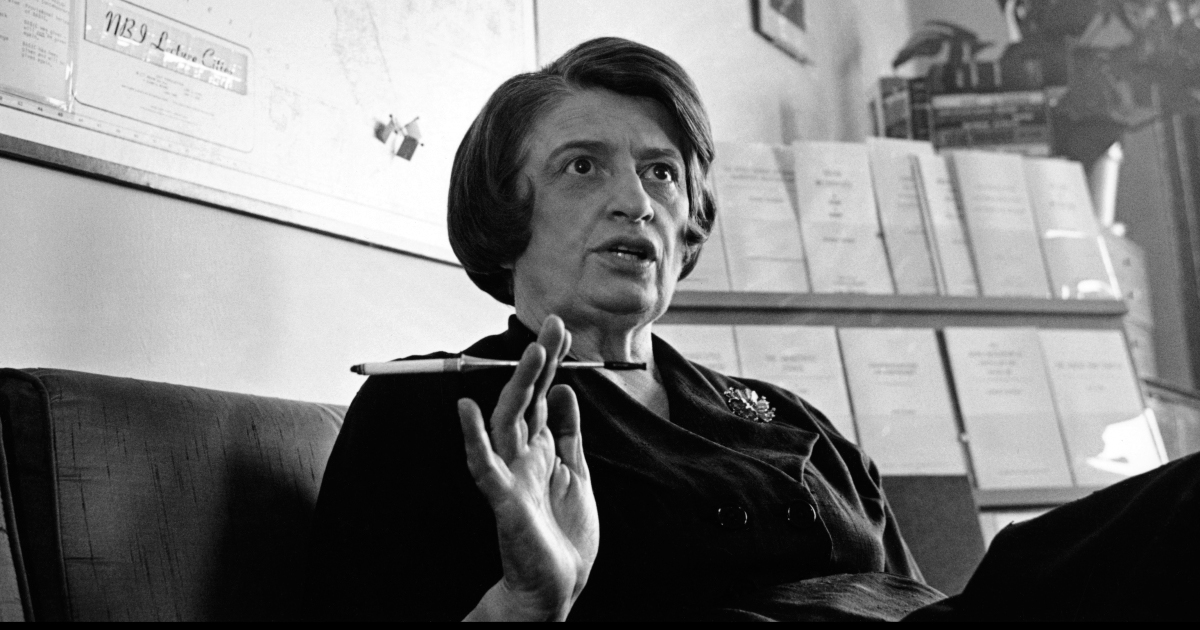

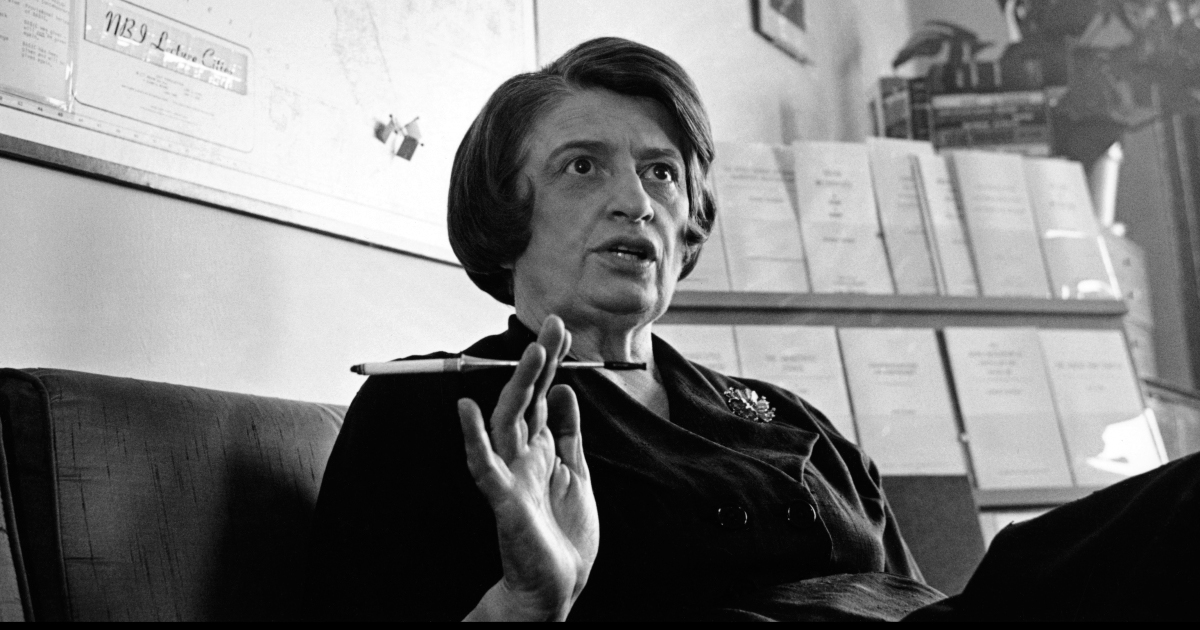

Images: 1st, Ayn Rand, photo by Cornell Cappa; 2nd, Patricia Neal (as Dominique Francon) shows the proper Randian woman-worship for Gary Cooper (as Howard Roark) in the 1949 film version of The Fountainhead; 3rd, Atlas, statue by Lee Lawrie that is often identified with Objectivism and has been used as a cover for Atlas Shrugged.

People know my views on representation in life, science and art. Theoretically, the announcement of the steampunk anthology The SEA is Ours (guided by editors Goh and Chng under the auspices of Rosarium Press) would have been cause for celebration and a welcome showcasing of new and neglected talents not gleaned from the default SFF demographic.

People know my views on representation in life, science and art. Theoretically, the announcement of the steampunk anthology The SEA is Ours (guided by editors Goh and Chng under the auspices of Rosarium Press) would have been cause for celebration and a welcome showcasing of new and neglected talents not gleaned from the default SFF demographic.