Ancestors Watch Over Her: Aliette de Bodard’s Space Operas

Thursday, May 30th, 2013Note: this is part of a series in which I discuss works of the contributors to The Other Half of the Sky. Links to other entries in the series appear at the end of each discussion.

By 2011 I had reached the point where I found SFF-as-usual intolerable, as a cross-section of my blog entries will attest. The blinkered parochialism, the impoverished imagination, the retreading of exhausted tropes and regressive clichés left me annoyed and – the kiss of death – bored. So before giving up on the genre altogether, I went out into the edges where the shrubs aren’t all pruned into the same shape and looked around for unruly life.

By 2011 I had reached the point where I found SFF-as-usual intolerable, as a cross-section of my blog entries will attest. The blinkered parochialism, the impoverished imagination, the retreading of exhausted tropes and regressive clichés left me annoyed and – the kiss of death – bored. So before giving up on the genre altogether, I went out into the edges where the shrubs aren’t all pruned into the same shape and looked around for unruly life.

One of the names that popped up was Aliette de Bodard, a French-Vietnamese computer engineer. Her two major worlds are a fantasy Aztec universe in which gods are real; and a near-future SF one in which North America is divided between two superpowers: a still-powerful Aztec oligarchy (Mexica) controls the South, an empire of pre-Manchu-invasion Han Chinese (Xuya) the West. There’s a shrunken USA in the Northeast and both Incan and Mayan polities are still extant.

The Mexica are an continuation of the pre-conquista Aztec culture whereas the Xuya are a Confucian society that has retained extended families, age seniority, scholar supremacy and ancestral worship, though its women can attain high official positions as well as practice polyandry. Two Xuyan stories were originally on the site: “The Lost Xuyan Bride” and “The Jaguar House, In Shadow”. I liked them for reasons of both style and content, including the non-Anglo settings and minor-key endings, and said to myself, This is prime space opera material. Let’s see if her future Xuyan stories unfold amid the stars.

To my delight, the Xuyan stories that followed the first two (“The Shipmaker”; “Shipbirth”; “Scattered along the River of Heaven”; “Heaven under Earth”; “Immersion”; “The Weight of a Blessing”; On a Red Station, Drifting; “The Waiting Stars”) indeed took to the stars and made the universe larger and deeper. Several ingredients got added when de Bodard made her cultures interstellar: memory implants that literally allow “worthy” descendants to get advice from their ancestors; Minds (hybrids of Iain Banks and Farscape equivalents) who run starships and space stations, their abodes designed by feng shui adepts; and the Dai Viet spacefaring culture, a “softer” Confucian society based on extrapolation of an imperial Viet on earth that threw off both French and Chinese invaders, though it must still fight the other powers (Mexica, Xuyan and the generically named Galactics, European/US proxies) to maintain territory and status.

Within this setting, de Bodard explores the rewards and problems of extended families and of hierarchical societies; the wounds and scars of imperialism and colonization and the shortcomings of different types of ruling structures; the clashes between societies and between classes within each culture; alternative family arrangements (from male pregnancy to lesser/greater partners in dyadic marriages, the ranking determined by collective standards); the promise and danger of immersive, invasive neurotechnology; the dilemmas of creating Minds, Borg-like immortals embedded in starships and space stations, born at great peril by human mothers and considered family members – genii loci and living ancestors in one.

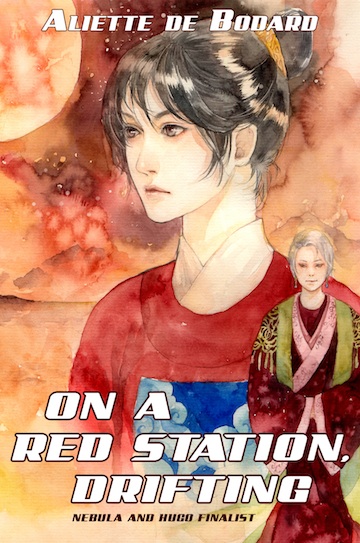

As a representative slice of this universe, the novella On a Red Station, Drifting (Immersion Press, $14.95 print, $2.99 digital) takes place on Prosper, a Dai Viet space station inhabited by essentially a large extended family of distant relatives plus a small Xuyan contingent. The story centers on the conflict between two powerful women: Lê Thi Linh, a scholar and magistrate in political exile who requests asylum on the station, and her cousin, Lê Thi Quyen, who has become stationmistress by default. Added to the mix are the station Mind who is slowly but inexorably failing, the agendas of other members of the Lê immediate family, and the strain put on Prosper’s people and resources by the faraway yet intrusive interstellar wars.

The story starts in media res, as is de rigueur for SF, and shifts back and forth between Linh and Quyen as (unreliable) narrators. Both are supremely capable and accustomed to authority, yet have cracks in their self-esteem for reasons related to their status. As a result, they are hypersensitive to slights, real and perceived. Their prickly pride and the Dai Viet culture’s standards of obliqueness and reticence set up the stage for a confrontation that pulls others into its vortex. During the ensuing battle of wills, many of the characters in Red Station cross into gray ethical territory or outright emotional cruelty.

De Bodard navigates deftly through this complex, polyphonic structure that’s part family saga, part cultural and political exploration, part space opera – but (happily) without blazing plasma guns, macho messiahs or standard father/son convolutions. None of the story’s devices are original but many are freshly recast: the unstable AI (de Bodard’s Minds are direct descendants of Joan Vinge’s Mactavs in “Tin Soldier”, including their gender); the space station in jeopardy (in this subcategory, Red Station ties as my favorite with C. J. Cherryh’s Downbelow Station and M. J. Locke’s Up Against It); neural/VR familiars (here explicit ancestral presences); design magicians (in this universe, the multi-skilled engineers who shape the stations/ships and their resident Minds).

The family dynamics are complex but clear and, as is typical of de Bodard’s stories, center on interactions between second-degree relatives rather than the more common first-degree ones. The two principals are well realized, with all their strengths, flaws and blind spots – though Linh is given more distinguishing small idiosyncrasies than Quyen. However, secondary characters remain quasi-generic types, with the partial exception of Quyen’s tortured brother-in-law and the fleetingly glimpsed but unforgettable Grand Master (Mistress) of Design.

There’s enormous tension in the story despite its leisurely pace, generated by the jeopardies inherent in the situation (annihilation of Prosper and its people is a real possibility and can come from several directions, including their own side) and also from the fact that none of the many subplots are completely resolved. Nor are any of the characters, several chafing against societal roles and expectations, fully reconciled to their fates or to each other. In this, Red Station is far closer to mainstream literary novels than the neatly tied endings common in SFF.

The style, straightforward with occasional flourishes, serves the story well: the membrane of illusion is never punctured. Vivid touches, from subtly nuanced poetry to mention of war-kites (a Yoon Ha Lee influence?) to xanh (read cricket) fights do much to make the Viet culture come to life – although if you’ve read other stories in this universe, you notice the recycling of fish sauce, zither sounds and wall calligraphy as cultural shorthands.

The most striking attributes of Red Station are not its intricate worldbuilding and plot, unusual and well-executed as they are. What makes it stand out is that its two fulcrums are women who clash over primary power, not over lovers, children or proxy power through male relatives; and that the story is set entirely within the Dai Viet context, making it the norm rather than an “exotic” variant juxtaposed to a more easily recognized “default”. Similar recastings distinguish all of de Bodard’s space operas and I, for one, hope she continues telling us stories of this universe. She deserves her recent Nebula award.

The most striking attributes of Red Station are not its intricate worldbuilding and plot, unusual and well-executed as they are. What makes it stand out is that its two fulcrums are women who clash over primary power, not over lovers, children or proxy power through male relatives; and that the story is set entirely within the Dai Viet context, making it the norm rather than an “exotic” variant juxtaposed to a more easily recognized “default”. Similar recastings distinguish all of de Bodard’s space operas and I, for one, hope she continues telling us stories of this universe. She deserves her recent Nebula award.

Cover art by Nhan Y Doanh

In the same series:

The Hard Underbelly of the Future: Sue Lange’s Uncategorized