Evghenia Fakinou: The Unknown Archmage of Magic Realism

Wednesday, August 26th, 2015Note: There has been intermittent discussion in SFF about the relative invisibility of non-Anglophone works. These rumblings have once again gained volume following the awarding of a Hugo to a novel translated from Chinese (Liu Cixin’s Three Body Problem, translated by Ken Liu). Below is an essay about another major unrecognized talent handicapped by writing in a language other than English. The essay first appeared, with minor variations, in SFF Portal.

—–

A while ago, I wrote an essay about the fact that writers feel free to use Hellenic contexts (myths, history, location), blithely assuming they know my culture well enough to do so convincingly. I mentioned that contemporary Hellenic literature is virtually unknown in the Anglophone world beyond Elytis, Seféris, Kaváfis and Kazantzákis – all of whom belong to the thirties. In effect, it is fashionable to pronounce Hellenic paradigms passé along with all other ‘Eurocentric’ sources, without ever having read Hellenic literature of any era. Lest you think I’m indulging in special pleading, this lacuna has been noticed and discussed by many non-Hellenes including Roderick Beaton, a formidable literary presence with a truly deep knowledge of my history and culture.

A while ago, I wrote an essay about the fact that writers feel free to use Hellenic contexts (myths, history, location), blithely assuming they know my culture well enough to do so convincingly. I mentioned that contemporary Hellenic literature is virtually unknown in the Anglophone world beyond Elytis, Seféris, Kaváfis and Kazantzákis – all of whom belong to the thirties. In effect, it is fashionable to pronounce Hellenic paradigms passé along with all other ‘Eurocentric’ sources, without ever having read Hellenic literature of any era. Lest you think I’m indulging in special pleading, this lacuna has been noticed and discussed by many non-Hellenes including Roderick Beaton, a formidable literary presence with a truly deep knowledge of my history and culture.

In my essay I also stated that Hellás may be home to the best magic realist alive right now: Evghenía Fakínou. In my estimation, she’s better than Salman Rushdie, Louis de Bernières, Laura Esquivel, Alice Hoffman or Orhan Pamuk. Her work does not suffer from the defects that occasionally mar their often outstanding work – Rushdie’s and Pamuk’s self-congratulatory longueurs and cardboard characters (their women especially), de Bernières’ lapses into the generic, Esquivel’s by-the-numbers sentimentality, Hoffman’s arch quirkiness. However, Fakínou’s original language and culture are heavy strikes against her. Only two of her novels have been translated, into indifferent English (a common fate, because the two languages are as different as two Indo-European cousins can be).

Fakínou was born in Alexandria in 1945, to working class migrant parents who hailed from the Dodecanesean island of Symi (a beautiful but stark place, whose cosmopolitan wandering people earned their living by fishing, sponge diving and with a formidable merchant marine fleet that played a significant part in the 1821 War of Independence). Her family returned to Athens when she was a child. She studied graphic arts and worked for several years as a graphic artist, illustrator and tourist guide. In 1976, she launched a children’s puppet theater show, Tin Town, which became very successful. Think politicized and stylistically circumscribed Sesame Street and you get the picture. She started writing children’s books first, then novels starting in 1982 – about twenty so far, plus collections of linked stories.

Fakínou’s books have won several awards and are wildly popular in Hellás: none has ever gone out of print, aided by the Hellenic publishers’ sane policy of small runs. Her writing combines three attributes, each of which would make her work addictive by itself: compelling plots, vivid characters and atmospheric settings. She is a mistress of creating sustained polyphony, a skillful puppeteer whose strings never become visible. Each of her characters jumps from the page, fully alive. Each of her books is distinct; she never resorts to clichés or cookie-cutter tactics, never repeats a successful recipe. In some cases she sticks to one narrator, first or third person; in others she switches between viewpoints – all with the illusion of effortlessness that distinguishes great dancers.

Fakínou’s books have won several awards and are wildly popular in Hellás: none has ever gone out of print, aided by the Hellenic publishers’ sane policy of small runs. Her writing combines three attributes, each of which would make her work addictive by itself: compelling plots, vivid characters and atmospheric settings. She is a mistress of creating sustained polyphony, a skillful puppeteer whose strings never become visible. Each of her characters jumps from the page, fully alive. Each of her books is distinct; she never resorts to clichés or cookie-cutter tactics, never repeats a successful recipe. In some cases she sticks to one narrator, first or third person; in others she switches between viewpoints – all with the illusion of effortlessness that distinguishes great dancers.

To top this, Fakínou has what for me is the quintessential gift of the rare true storyteller: her novels are full of echoes. She seamlessly interweaves history and (usually revisionist) mythology as she roams through six millennia of my people’s ghost-inhabited, monument-strewn cultural landscape. Yet there is no infodumping, no slowing of the plot momentum to flaunt her knowledge. If her readers are not aware of the background she evokes, the stories are still absorbing. But if they are, her stories are simply unforgettable: they etch themselves on one’s long-term memory and never fade.

To give you a sense of Fakínou, I will briefly outline the two of her novels that have been translated in English, fully aware that neither my descriptions nor the translations convey the potent magic she weaves.

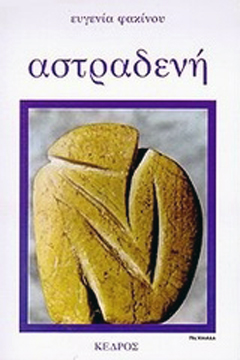

Astradhení (Fakínou’s first novel; the word is a rare first name that means ‘starbinder’) starts deceptively as YA. We get carried along on the matter-of-fact, stripped-down voice of its narrator, a young girl whose family has been ripped off their island home by misfortune: her little brother’s death devastated them both emotionally and financially. The transplantation to Athens brings the woes that always beset immigrants: the ridiculing of accents and customs, the loneliness and alienation, the forced homogenization into marginal/ized urban living.

So far, so common, if beautifully rendered. But a deep river runs underneath the main narrative: Astradhení has visions of the young priestesses of pre-Olympian Ártemis who danced around the open-air altar of the goddess wearing bear pelts. To shake us out of the easy YA classification, the visions don’t bring her insight, solace or strength. At the close of the story, an acquaintance of her father starts to rape Astradhení. The final words are her anguished protestations, girl and priestess fused into one.

Astradhení’s visions are rips in the fabric of time, vouchsafing us glimpses of a (real or half-dreamt) past when women had power, a place as beguiling as – and far less sugarcoated than – Marion Zimmer Bradley’s Avalon. In that world, Astradhení would have been a seer. Rape, embedded in the overt misogynism of both Hellenic and Byzantine traditions, is a bleeding wound in my culture and the book was notable just for bringing it up (a visual parallel happens in Angelópoulos’ film Landscape in the Mist).

To Évdhomo Roúho (The Seventh Garment) tells how women carry history on their shoulders, like the Karyatids or the wives of folk ballads, buried alive so that bridges would stand. Three generations of women – Maiden, Mother, Crone – gather to perform an ancient ritual over the death of the last man in the family: the belief is that for his spirit to cross safely to the Otherworld, the women must line up the garments of the family’s seven firstborn sons, one from each generation (underlining the so far unquestioned requirement for sons). The last garment is missing, which triggers the story’s crisis.

To Évdhomo Roúho (The Seventh Garment) tells how women carry history on their shoulders, like the Karyatids or the wives of folk ballads, buried alive so that bridges would stand. Three generations of women – Maiden, Mother, Crone – gather to perform an ancient ritual over the death of the last man in the family: the belief is that for his spirit to cross safely to the Otherworld, the women must line up the garments of the family’s seven firstborn sons, one from each generation (underlining the so far unquestioned requirement for sons). The last garment is missing, which triggers the story’s crisis.

Through the conversations and first-person narrations of the three women, we get strobelight views of several epochs of Hellenic history: the War of Independence against the Ottoman Empire; the 1922 catastrophic defeat of the Greek army by its Turkish counterpart that uprooted the Hellenes from Asia Minor, an integral part of their homeland for four millennia; the trials of the refugees, who met a mixed welcome on the mainland; the resistance in World War II, callously betrayed by its ostensible allies; and contemporary globalization, with its atomizing effects. The men these women remember and mourn were mostly loved (though rape figures prominently again) but mostly absent: killed, imprisoned, exiled, forced to emigrate. Several myths are woven into this tapestry: Démetra’s tormented search for Persephóne and also the wanderings of Odysséus, fused with folk stories of sea-gods, both pagan and Christian.

Though Fakínou made up the details of the ritual, it is grounded in the mourning customs of the Aegean islands. The women in her story, unsung singers, maintain the traditions while subverting them at the same time. In the end, the grandmother quietly pierces herself and bleeds to death so that her drenched tunic can serve as the missing garment. The chthonic powers accept it. By doing this she becomes an ancestor, a lofty position previously forbidden to women, and heals several rifts at once, though probably briefly.

Fakínou’s books are full of vision quests, awakenings, boundary crossings. All have open endings, with their protagonists poised at thresholds on the last page. At the same time, they make their readers whole by reclaiming a past that might have led to an alternative future. Fakínou is a windwalker, a weaver of spider silk. I’m sorry she is not world-famous, but even sorrier for the dreamers who will never get a chance to lose – and find – themselves in her work.

References and Related Essays

The String Cuts Deeper than the Blade

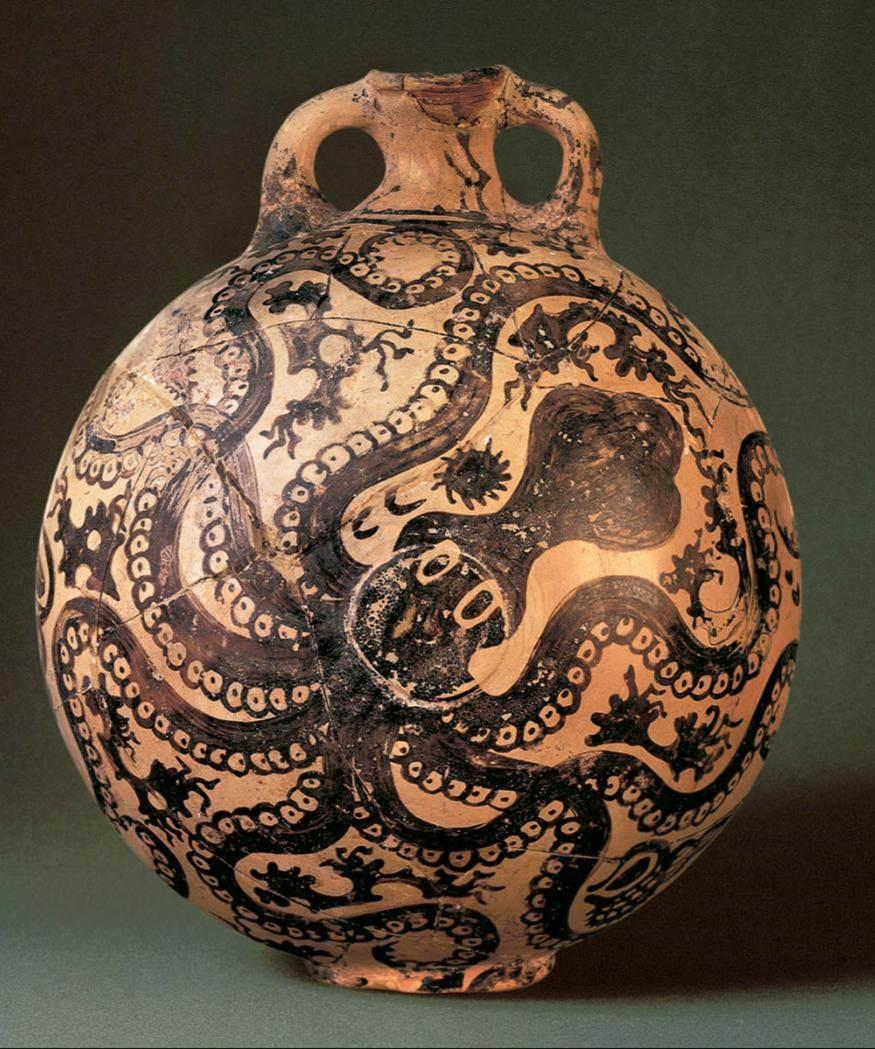

The Hyacinth among the Roses: The Minoan Civilization

Being Part of Everyone’s Furniture; Or: Appropriate Away!

Yes, Virginia, Hellenes Have Christmas Traditions

Safe Exoticism, Part 2: Culture

Herald, Poet, Auteur: Theódhoros Angelópoulos (1935-2012)

The Doric Column: Dhómna Samíou (1928-2012)

Close Your Eyes and Think of Apóllon

Hidden Histories or: Yes, Virginia, Romioi Are Eastern European (And More Than That)

The Blackbird Singing: Sapfó of Lésvos

If I Forget Thee, O My Grandmother’s Lost Home

Images

Evgenía Fakínou

Astradhení, first edition

The Seventh Garment, first edition