by C. W. Johnson

I’m delighted to once again host my friend Calvin Johnson, who earlier gave us insights on Galactica/Caprica, Harry Potter, The Game of Thrones, Star Trek: Into Darkness, Interstellar, and the works of Hanya Yanagihara, Ken Liu and Liu Cixin.

Science fiction is full of ideas. But the ideas in science fiction seldom have the depth and rigor of ideas in science, or in philosophy, or politics and ethics. The reason I say this is: in fiction, the game is rigged. The debates are one-sided. The author gets the first, middle, and last word.

Science fiction is full of ideas. But the ideas in science fiction seldom have the depth and rigor of ideas in science, or in philosophy, or politics and ethics. The reason I say this is: in fiction, the game is rigged. The debates are one-sided. The author gets the first, middle, and last word.

This is not to say that the ideas in science fiction cannot capture the imagination. Indeed many classic SF stories that have inspired careers or even presaged the future. But not all have. The ideas in SF are not fully developed theories or philosophies, but more like Edison’s famous ten thousand attempts at making electric light: we remember the one that worked and forget, mostly, the ten thousand that didn’t.

But the ones that work, either through vivid imagery or asking difficult questions or getting lucky and “predicting” the future, stay with us. Once in a great while, there is even a story that causes me to rethink my opposition to describing science fiction as a “literature of ideas.”

Such as Kim Stanley Robinson’s latest novel, Aurora.

#

Let me explore the concept of fiction as being rigged. Science fiction typically assumes some future technology, whether it be interstellar travel or time travel or life extension, is possible. It is only after such an assumption that we arrive at the “idea” in science fiction: a fable about unintended consequences–step on a butterfly in the Cretaceous, change all of history–or to ask, a la James Blish, Who does this hurt?

But these moral fables–for that is what they really are–gloss over the assumption of a technology. Many enthusiasts believe in a kind of technological manifest destiny: we can achieve any technology, if only we are smart enough, or put enough effort into it, or let market forces achieve it.

In support of such a view the Manhattan Project, the Apollo Project, and Moore’s Law are often cited. Such citations often ignore the fact that those successes were a matter of scaling known engineering. The basic physics of fission reactions, of space flight, and of transistors were known long before those projects and observations began.

Here’s the problem: one should not conclude, by way of analogy, that any technological goal can be achieved by sheer perspiration. The easiest and most obvious example is in human health. By a wide margin, the most crucial leaps to better health have been good sewage management and vaccines, followed by antibiotics. But after that it becomes much harder. If market forces alone were enough, we would have conquered cancer long ago, but while some cancers are curable, many others we can at best slow down. (This, of course, is because “cancer” does not have a single etiology.) There are start-up firms devoted to engineered immortality, but none have added a single day to human life spans.

In short, just because you can imagine it doesn’t mean it is actually possible. I’m still surprised how resistant people are to this basic principle.

#

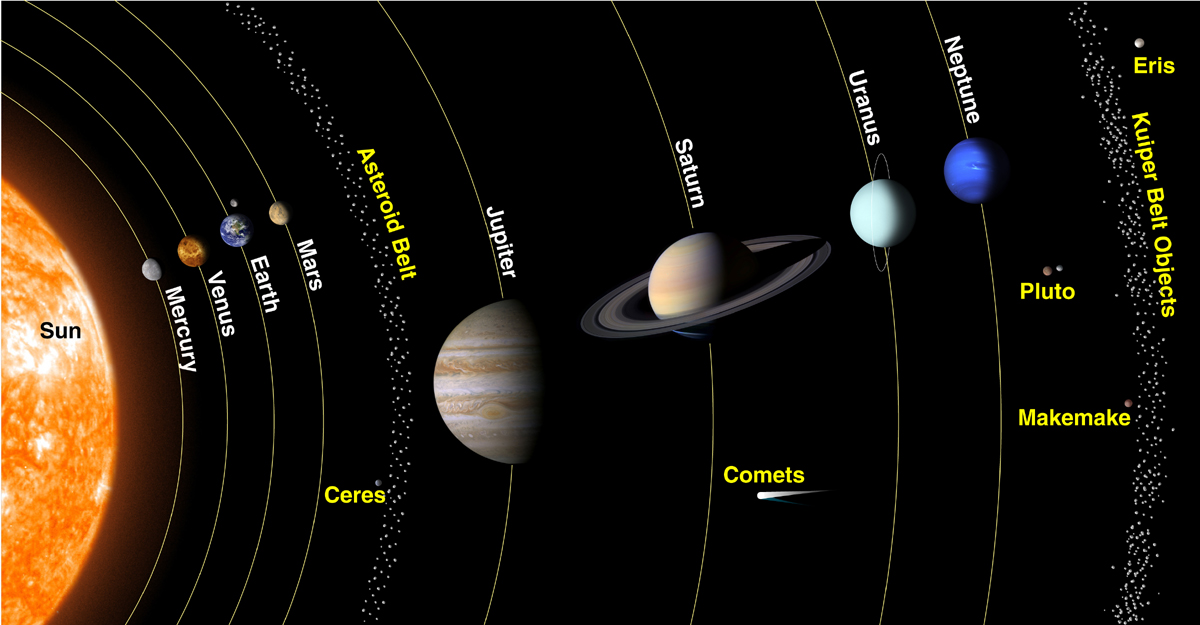

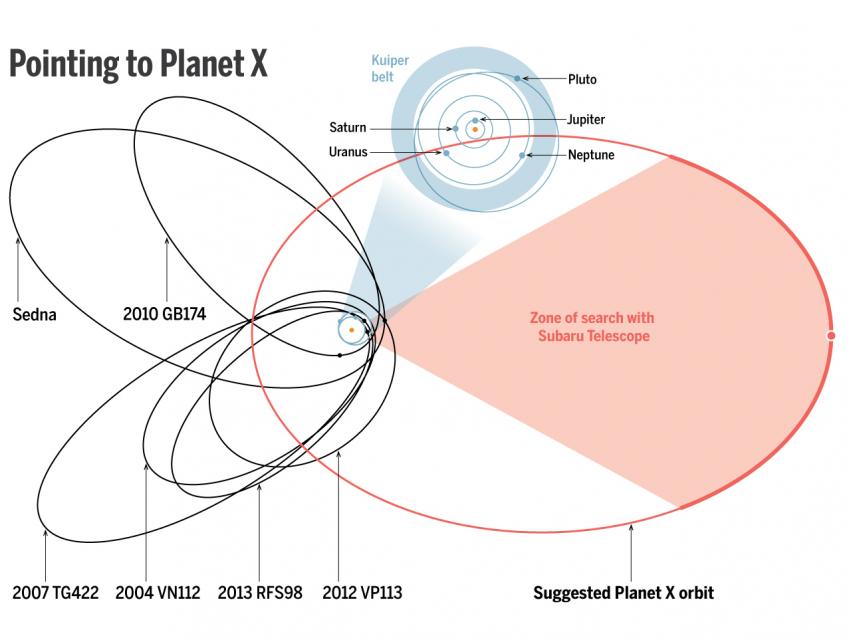

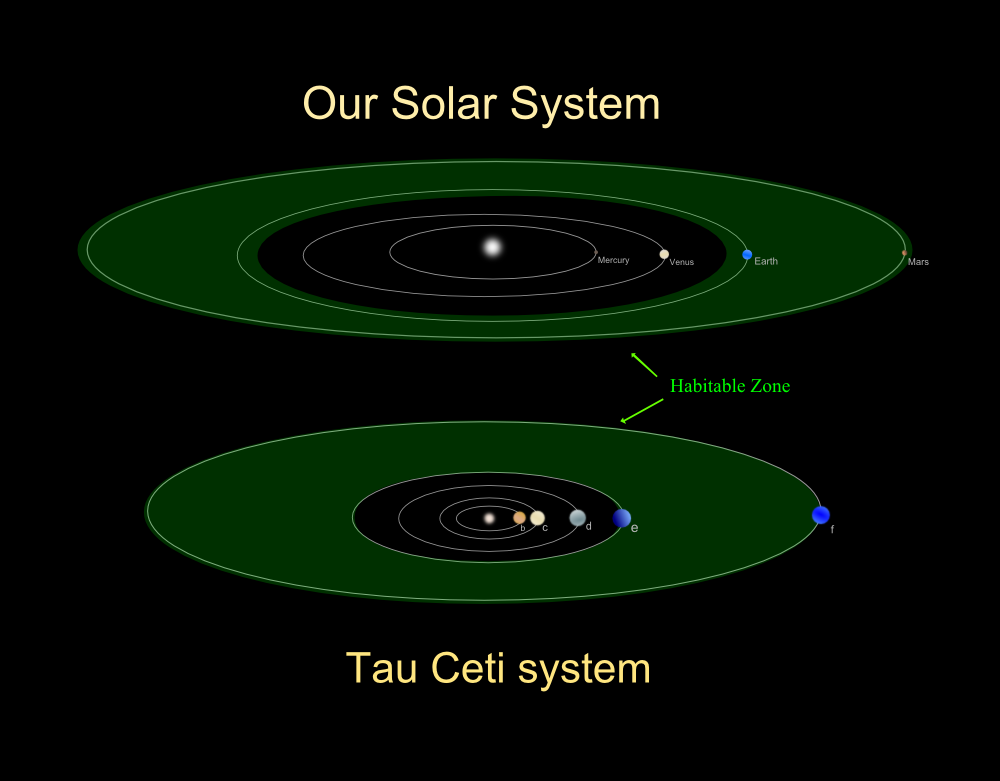

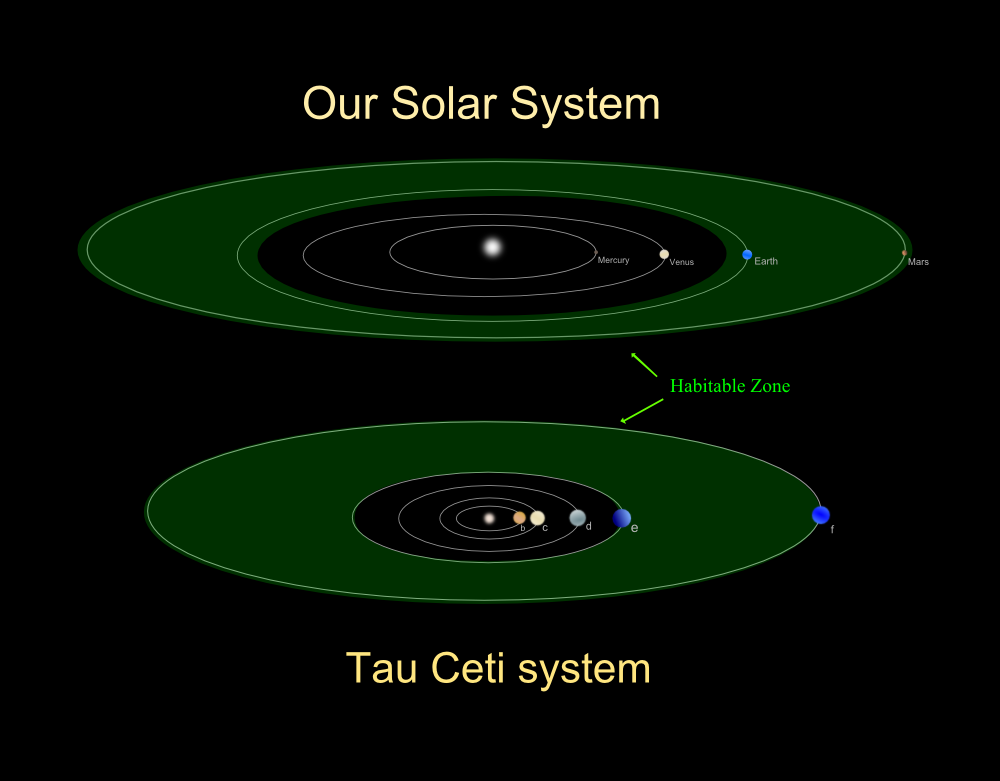

Of course, interstellar flight might seem like a straightforward if ambitious scaling-up of the Apollo program. But Tau Ceti, one of the closest singlet G-class stars (i.e., like our sun), known to have at least five planets, is almost 100 billion times farther away than our moon. That’s a lot of scaling; by comparison, Moore’s law from 1971 to today has seen a mere one million times increase in the number of transistors on a chip.

And Moore’s law has a cost. As transistors shrink, the chip foundries become increasingly complex, costing over US$1 billion to build, and using prodigious amounts of caustic chemicals. The market pressures so far have masked these costs, but even so the market for personal computers has saturated and it is the market for phones which has largely driven further developments. But now with billions of phones across the globe that market too is becoming saturated. We’ll see replacements, of course, but that is linear; the pressure for geometric growth described for Moore’s law is diminishing.

And in a way, this is the story that Robinson tells in Aurora.

#

[Click twice to see full-size image]

Some minor spoilers ahead; I’ll keep them to a minimum, but I will outline some key plot points. If you want me to cut to the chase, it’s this: in my opinion, Aurora is the best hard science fiction novel since Benford’s Timescape, and Robinson achieves this by blowing up the usual assumptions, and jumping up and down on them until they are ground into tiny bits.

Aurora is about interstellar travel. A ship, one of many, is sent at one-tenth of the speed of light to Tau Ceti. This journey takes almost two centuries, and so generations are born, live, and die aboard the ship.

In Robinson’s novel, interstellar travel is possible, but costly. First and foremost, keeping a closed ecosystem running is not easy. Robinson has hinted at these concerns in previous novels, in Icehenge and his Mars trilogy, and here he spells them out in detail, thinking out how a generation ship would work (and not work) to a degree not achieved before. The specific biochemistry is a little beyond me, but he is married to an environmental chemist and, most importantly, the principle is sound. Managing trace elements such as bromine isn’t easy: too little can have dire consequences, but too much and you have toxic effects. The designers of the starship had to try to predict how the ecosystem would behave over centuries. Robinson assumes the designers did a pretty good job, but even in a pretty good job a few miscalculations or oversights can grow over time.

Just as big a source of problems as technology is politics. Robinson’s politics lean to the communitarian and the ship’s governance reflects this, but he recognizes that every polity can fracture and every system of governances privileges some over others. In this he echoes LeGuin’s The Dispossessed, a novel I first read many years ago in a class Robinson taught at UC Davis, and which is also set in the Tau Ceti system. And as in Robinson’s Mars trilogy, when society is stressed, some people respond badly, even violently.

The politics back home, i.e., on Earth, also shifts. People lose interest in interstellar travel, which soaks up enormous resources, leaving the crew of the ship to their own devices when things go awry.

Most SF novels assume that Things Work Out in the end. A crisis convenient for a thrilling plot pops up, but Our Heroes/ines figure out it in the nick of time, and humans triumph over the odds. This future version of Manifest Destiny has been here since the pulps and never really gone away.

Robinson attacks this idea, in detail and in depth. The technology goes wrong, and there is no magical fix, and people die. (Not always; there are some spectacular saves.) The politics goes really wrong, and more people die.

Moreover, Robinson suggests that Manifest Destiny breaks apart upon the rocks of the Fermi paradox, i.e., if there is intelligent life out there, why haven’t we heard from it? Recently I wrote of the Chinese author Cixin Liu’s solution to the Fermi paradox, a dark and paranoid vision.

Robinson’s solution to the Fermi paradox is more measured and frankly more believeable than Liu’s. In most science fiction novels people on alien worlds can easily breathe the air and eat the native organisms with no ill effect. This has always bothered me, because, for example, humans actually can only tolerate a fairly narrow range of atmospheric mixtures; and as for food, we’ve had to co-evolve to digest plant and animal tissues.

Robinson suggests that most planets are either sterile, and would require centuries or millenia of terraforming–in stark contrast to the decades he unrealistically postulated in his Mars trilogy– or the established life would be so biochemically hostile at a fundamental level that humans could not survive. The latter is of course speculative, but speculation is the game in science fiction.

The universe is full of life in Robinson’s vision, only that life is each trapped on its planet of origin. We can’t conquer distant stars; the costs are too great.

#

Aurora is not a perfect novel. Like most hard SF novels, it is plot and exposition heavy. Only three characters are fully realized, and one of those is the ship’s artificial intelligence. The bulk of the prose is plain and to-the-point, which Robinson cleverly covers by having the ship itself be the narrator. Only in the opening and closing sections, not narrated by the ship, does the prose sing and does Robinson use his literary skills fully.

But few novels in my reading have examined the technology and the difficulties therein in as much detail, acknowledging that science and people are always flawed and limited. I seldom say this, but Robinson’s novel is truly an “instant classic” of SF, and the hardest of hard SF at that. The year 2015 isn’t over, but Aurora should be a shoo-in for major award nominations. Not only that, it should win.

Related Articles:

Making Aliens (six part series, starts here)

Once Again with Feeling: The Planets of Gliese 581

The Death Rattle of the Space Shuttle

If They Come, It Might Get Built

Why We May Never Get to Alpha Centauri

Damp Squibs: Non-news in Space Exploration

Images: 1st, a two-torus starship like Aurora; 2nd, the Tau Ceti system; 3rd, Kim Stanley Robinson

We cannot cross until we carry each other,

We cannot cross until we carry each other,