“But remember. Make an effort to remember. Or, failing that, invent.” – Monique Wittig, Les Guerillères

A story of mine, Dry Rivers, just appeared in Crossed Genres. It takes place in an alternate universe in which the Minoan civilization survives the Thera eruption. Coincidentally, I recently finished a book by Dr. Cathy Gere, Knossos and the Prophets of Modernism. The author discusses how the Minoan civilization served as a mirror that reflected the social biases of the era of its discovery – particularly of its idiosyncratic excavator, Arthur Evans.

A story of mine, Dry Rivers, just appeared in Crossed Genres. It takes place in an alternate universe in which the Minoan civilization survives the Thera eruption. Coincidentally, I recently finished a book by Dr. Cathy Gere, Knossos and the Prophets of Modernism. The author discusses how the Minoan civilization served as a mirror that reflected the social biases of the era of its discovery – particularly of its idiosyncratic excavator, Arthur Evans.

During the Bronze Age, several major civilizations blossomed contemporaneously around the Eastern Mediterranean. Many are familiar to most Westerners, if only by name – the Egyptians, the Sumerians, the Babylonians, the Hittites. But one was sui generis: the Minoans. Despite their extraordinary achievements, we know a lot less about them than we know about their neighbors. Their alphabet, Linear A, remains undeciphered. Nor do we know what language they spoke, though a few Minoan words still adorn the Greek tongue, such as thálassa (sea), lavírinthos (labyrinth, house of the double axes), hyákinthos (hyacinth) and kypárissos (cypress).

I have always been haunted and beguiled by that lost civilization. Most of my fiction, whether of the past or the future, fantasy or science fiction, involves the Minoans. Not only are they part of my biological and cultural legacy; they were also unique. Minoan art is instantly recognizable. It is possible that the Minoan civilization might have changed the flow of history, had it not been literally snuffed out by the apocalyptic explosion of the Thera (Santorini) volcano. Such was the magnitude of the catastrophe that it became a potent, defining myth that echoes down the ages, from Plato’s Timaeus to Tolkien’s Númenor: the drowning of Atlantis.

How distinctive and advanced were the Minoans? Cathy Gere argues that they were not. She suggests that the attempt to portray Minoan Crete as a pacifist, matriarchal haven of high sophistication is not supported by the archaeological evidence, but is mostly a fantasy (largely created by Evans) to act as a paregoric to a world reeling from several major wars. Gere’s style is vivacious, articulate, elegant – and she knows her history. It is also true that Evans’ reconstructions of the Knossos palatial complex and its frescoes were heavy-handed and arbitrary. And in time-honored archeological fashion, he withheld evidence and suppressed careers that contradicted his theories.

If Gere’s book were your only source on the Minoans, you would come away well informed, highly entertained and with the impression that they were just a standard variant of the Bronze Age Levantine cultural recipe. And since Linear A has not been deciphered, the Minoans cannot tell their own story. However, extensive frescoes and other artifacts that have been gradually emerging from Akrotiri, the Theran equivalent of Pompei, support major portions of Evans’ theory. Because burial under volcanic ash kept everything intact, no question of false reconstruction intrudes. The frescoes didn’t adorn palaces, but residential houses. This fact alone says something about the Minoan culture. So does the finding that the houses were multi-storied and had hot and cold running water – amenities forgotten by their successors and the rest of Europe for almost four millennia.

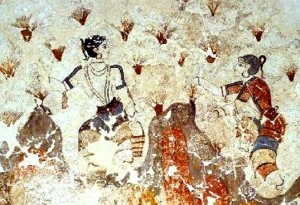

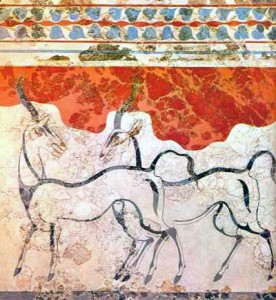

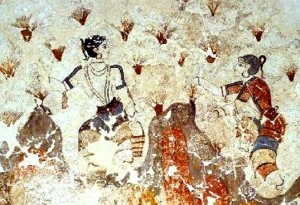

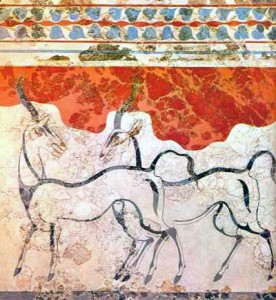

Even more indicative are the subjects of the frescoes: women gather saffron crocuses, boys box, crowds watch a regatta in a harbor, swallows intertwine over lilies, gazelles gambol. War is conspicuously absent – not a single battle scene, not one weapon, not even a chariot. Gods and kings, with their usual smitings, are also conspicuously absent. The focus is on nature and daily activities. This is true of all Minoan art, from frescoes to pots to seals. Too, there is a fluidity and exuberance that sets Minoan art apart from its Egyptian and Babylonian equivalents, which are oppressive with their will to power despite their beauty. And women are everywhere, always more prominent and detailed than the men, in stark contrast to their absence or subordinate status in the art of Crete’s contemporaneous neighbors.

In all other Bronze Age East Mediterranean cultures, the Great Goddess (Isis, Ishtar, Inanna) suffered dethronement at the hands of her Consort/Son. But in Crete she retained her primacy till the Mycenaeans arrived after the volcano eruption. This does not automatically imply that Minoans were matriarchal or that women enjoyed equal status in Crete. However, the scenes depicted in Minoan art suggest that women had significant rights and were active and valued participants in society. This is not surprising. Merchant and seafaring cultures are flexible and open to new ideas which they encounter willy-nilly, and Minoan Crete was both: the Egyptian, Babylonian and Hittite archives as well as the economic system deduced from the excavations indicate that the Minoan hegemony was light-handed, localized, sea-based and economic rather than military.

There is no doubt that Minoan Crete was not the utopian paradise that Evans envisioned. For one, if the Minoans had insisted on wearing only white helmets, they wouldn’t have lasted long enough to leave any legacy, wedged as they were between nations intent on empire. For another, the Minoans did have social classes: distinctions are clearly visible in the frescoes. However, it makes me happy and hopeful to think that there may have been at least one high civilization – the first one in Europe, in fact – that was not intent on conquest, enslavement and slaughter. That once perhaps there existed a people who were content to build and sail merchant ships, create ravishing art, sing harvest songs and love ballads… and gaze at the stars while sipping wine in the warm summer nights of the Aegean.

Further reading:

Introduction to Akrotiri

Minoan portal

Frescoes:

Top, “La Parisienne”, Knossos, Crete; Middle, Saffron Gatherers (detail), Akrotiri, Thera; Bottom, Antelopes (oryx), Akrotiri

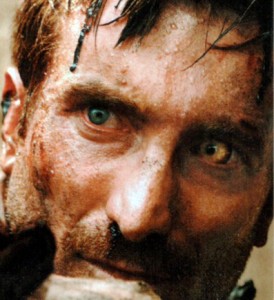

I saw District 9 yesterday. This gory bore won an 88% rating at the Tomatometer? As well as rave reviews from intelligent, well-educated people across the age spectrum? Once again, as with Star Wars, I find myself wondering if I’m in a parallel universe.

I saw District 9 yesterday. This gory bore won an 88% rating at the Tomatometer? As well as rave reviews from intelligent, well-educated people across the age spectrum? Once again, as with Star Wars, I find myself wondering if I’m in a parallel universe. The cruelties of segregation, the plight of refugees, our treatment of Others — those are burning subjects. So is the question of how we would interact with sentient aliens. None of them gets real treatment here. Instead, the film manipulates its viewers into feeling virtuous by being superficially “daring”. District 9 is neither science fiction nor social commentary; it’s violence porn — or, as producer Peter Jackson himself called it on io9, splatstick.

The cruelties of segregation, the plight of refugees, our treatment of Others — those are burning subjects. So is the question of how we would interact with sentient aliens. None of them gets real treatment here. Instead, the film manipulates its viewers into feeling virtuous by being superficially “daring”. District 9 is neither science fiction nor social commentary; it’s violence porn — or, as producer Peter Jackson himself called it on io9, splatstick.

Several decades ago, James Tiptree Jr. (Alice Sheldon) wrote a story in which aliens eyeing the lush terrestrial real estate introduce something in the water or the air that makes men kill women and girls systematically, rather than in the usual haphazard fashion. Recent events have made me wonder if a milder version of Tiptree’s

Several decades ago, James Tiptree Jr. (Alice Sheldon) wrote a story in which aliens eyeing the lush terrestrial real estate introduce something in the water or the air that makes men kill women and girls systematically, rather than in the usual haphazard fashion. Recent events have made me wonder if a milder version of Tiptree’s  Of course, parity is not even remotely demanded — a mere one or two representatives often suffice as a sop (to such lows have we fallen). The bleatings about qualifications and tokenism are absurd, given the vast, stellar non-male non-white talent pool. The excuses sound even lamer (if not malicious) when one scans the predictable, often mediocre, rolodex-friend picks actually made in cases 1 and 2 above… and in more instances than I care to recall at other times.

Of course, parity is not even remotely demanded — a mere one or two representatives often suffice as a sop (to such lows have we fallen). The bleatings about qualifications and tokenism are absurd, given the vast, stellar non-male non-white talent pool. The excuses sound even lamer (if not malicious) when one scans the predictable, often mediocre, rolodex-friend picks actually made in cases 1 and 2 above… and in more instances than I care to recall at other times.

A story of mine,

A story of mine,