“The childishness noticeable in medieval behavior, with its marked inability to restrain any kind of impulse, may have been simply due to the fact that so large a proportion of active society was actually very young in years.” — Barbara Tuchman, A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century

Until recently, women died on the average younger than men, primarily in childbirth – though they also died from overwork, undernourishment and beatings, like the beasts of burden they often resembled, or were killed in infancy for having the wrong hardware between their legs. However, this changed in the last few decades. UN records indicate that most of the world’s aged are now women (ignoring the “girl gap” of China, India and other cultures that deem sons a sine qua non). Concurrently, biology is (reluctantly) coming to the conclusion that grandmothers, particularly maternal ones, may have made humans who they are.

Literature, whether mainstream or genre, has apportioned a good deal of its content to formidable crones, matriarchs and dowagers, both benign and malign. There is one genre, however, which if read exclusively conveys the impression that men live for ever (and get ever more potent and interesting as they do so) but a disease fells women the moment they go past the “peak attractiveness” so beloved of evopsychos. This genre is science fiction (SF). In an unusual reversal, it’s worse in books than in film/TV, of which more anon.

The age skewing may have to do with the simple fact that, conscientious efforts to the contrary, SF remains quintessentially American in all its parochial glory – and Americans are obsessed with youth (especially that of women) and terrified of aging, which they try to stave off or mask at all costs: from the Vi*agra craze, lethal side effects be damned, to the cracked-glaze look of older celebs to the transhumanist fact-free ravings about uploading into perfect, indestructible silicon bodies. In SF this is exacerbated by the genre’s adoration of unfettered individualism (for those who have the Right Alpha Stuff, naturally) and the finding-one’s-self quest motif, which devalues narratives that view people as parts of kinship webs and/or absorbed in multiple demanding vocations; if you identified the latter items as primarily “women’s” domains, go to the top of the class.

Two items have prompted me to revisit this literally hoary topic. One is the constant much-heat-little-light argument about representation and diversity in SF, from which discussions about age are conspicuously absent and primitive in the rare instances they occur. The other is the recent “PC censorship panels” petition to the SFWA – a crude intimidation attempt disguised by its originator as a fight for freedom of speech, with responses to it mostly (though not exclusively) split across age lines. The young(er) hopefuls on the Side of Good opined en masse that all “isms” will disappear from SF “when the old dinosaurs die”.

If only. You have much to learn, grasshoppahs. Take this paragraph and the next as free advice from a lifelong outsider who doesn’t gender-conform in either culture she’s lived in, is in the last third of her life, and has been in the “ism” trenches in all three thirds of it (though perhaps I should attach an invoice to this post: the more expensive the advice, the likelier to be heeded). The real determinant is not age, but entrenched power hierarchies and the sense of entitlement they foster. Age, particularly in the US context, rarely translates to power – especially for women, who are still considered disposable beyond decoration, un/underpaid labor and reproduction. Age may bring hardening of the arteries and softening of the upper and lower heads, but closed minds correlate far more tightly with automatically vested authority and membership in dominant groups. Clinging to power, rather than an attribute of age, is in fact a refusal to really grow up: even kids eventually learn to share their toys.

In most cultures, women never accrete authority or power no matter what their age and are rarely insiders in power networks even in dynasties. There are exceptions: some cultures treat older women as honorary almost-men when the “taint” of menstruation recedes. Also, in cultures that practice gender segregation and uproot women from their homes and blood kin, older women can wield proxy power over younger ones but solely in women-only spaces and aspects. As a net result, women often remain rebels till they die: they really have no other option if they don’t want to be pushed onto that permanently reserved ice floe – though they still get bypassed, ignored, belittled, ridiculed (along many axes, if they happen to have additional “defects” as defined by Faux News)… and plenty of them still get stoned or burned even before age makes them annoying and/or burdensome.

When the issue of age became too pronounced to ignore in the SF community, the usual reactions occurred. The primary response was the obligatory ritual of list compilations. This proved demoralizing, because even the most conscientious couldn’t come up with more than a dozen older women in SF novels and stories, even when counting secondary characters and women in their forties as “old” (in inadvertent harmony with prevailing US norms). Numbers were better in film and TV, which exposes a wrinkle brought further home to me in a wonderful review of The Other Half of the Sky by a discerning reviewer: she mentioned that the anthology contains only one old/er woman. My count had been different, but I went back anyway, counted again and came up with four or five aged protagonists in sixteen stories – more if you fold in characters in their forties, as SF apparently does.

This made me realize that SF readers ratchet down the age of women characters automatically and significantly, unless the writer employs in-your-face signaling techniques – something that can’t happen in visual media, no matter how “natural” the face lifts or hair dyes. Which brings us full circle to social norms. There’s a reason why SF readers don’t see old women, even when the author has explicitly imagined them as such: because it’s accepted and acceptable in the genre that women never attain the authority that accrues to men of equivalent age, experience and expertise – even though history shows otherwise, making much speculative fiction duller than fact.

The near-total excision (at both first and second remove) of old/er women in SF is a sign of timidity and conformism in a genre that proudly dubs itself visionary. Mainstream literature and other genres are literally a-swim with such protagonists. Without looking anything up or thinking hard, in mysteries there’s Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple and Lynda La Plante’s Jane Tennison. In fantasy/alt-history: Sylvia Townsend Warner’s Laura Willowes (The Loving Huntsman), Isak Dinesen’s Pellegrina Leoni (“The Dreamers”, “Echoes”), Joanna Russ’ Abbess Radegunde (Extra(ordinary) People); in historical fiction: Sarah Dunant’s Alessandra Cecchi (The Birth of Venus), Susan Fraser King’s Gruadh Inghean Bodhe (Lady Macbeth), Kate Horsley’s Gwynneve (Confessions of a Pagan Nun); in mainstream literature: Rita Sackville-West’s Lady Slane (All Passion Spent), Colette’s Renée Néré (La Vagabonde), Bertold Brecht’s unnamed grandmother (Die Unwürdige Greisin), Penelope Lively’s Claudia Hampton (Moon Tiger), Stratis Tsirkas’ Ariághne (Drifting Cities), Margaret Laurence’s Hagar Currie Shipley (The Stone Angel).

In stark contrast, women in SF are almost never shown as revered sages/mentors, seasoned leaders, knowledge propagators, memory keepers, inveterate hell-raisers, respected eccentrics – incarnations routinely available to older men that have the added perk of creating positive feedback power loops. As an additional handicap, older women don’t fit the finding-one’s-self quest pattern. They know who they are, what they’re doing and why. Their tragedies originate from other types of friction: opposing ideas of good from friends and allies; the realization that they will never get the credit or recognition their work merits; and larger brutal if inevitable losses, including the unraveling of painstakingly knit webs and the relentless diminution of one’s powers till the final journey to the dark.

As an exercise, I’m appending a story of mine that appeared in After Hours (#24, 1994). Ask yourself how old the hero looks in your mind’s eye, and whom you envision playing her in a film version. If the answer to either is a perky lacquer-skinned ingenue, ask yourself why.

Night Travels

The wanderer was not yet old, but she felt so — old and scarred and bitter. She had seen years of peace, when she was content to stay in libraries and dream within book covers… or find someone who sweetened her hours and stole a little of her stamina, a little of her self-sufficiency. She had seen years of war, when fires bloomed out of what had been cities and the finer shadings of peacetime faded into black. She had ridden in all weathers, sometimes the horse knowing more about where they were going, bloodstains mingling with rain or snow on her clothing. One great love she had had, and loved a little too long and too hard, more the glimpsed potential than what had been truly there. She was well-known, although an exile from her own land; people sought her advice, valued her friendship, desired her good opinion. She had been counsellor to powerful people and sometimes had led her own band of warriors.

But now she was weary.

She had just left the relative comfort of a manor behind her, having discovered that her patience with people was seriously eroded. For someone who had helped put almost all the present princes of the western provinces on their seats, losing lovers and children in the process, daily concerns had paled somewhat. Her ever-increasing courtliness had become a shield, a distancing device.

She had left in the late morning of a calm winter day, and was slowly guiding her horse over the downs. Here and there, a tuft of trees or a clump of rocks embroidered the eggshell-colored sky. A few whiffs of smoke from the widely separated human habitations dispersed lazily in the crisp air.

She was making her way down a dried riverbed, when she discerned another rider at the mouth of the valley. She approached unhurriedly — friend or foe, there was time.

He was perhaps in his late youth, with very long braided hair of the palest gold — just like the sun that came hazily through the cloud cover. His face was angular and weathered, with piercing storm grey eyes, matching his worn but clean garments. But the horse was enormous and black, and the weapons rivalled her own in quality and length of use.

“No one should have to travel in winter,” he said as she drew up.

“All seasons are the same for wanderers,” she replied.

“If you are going westward, I would be glad of company.”

She examined him. He withstood the scrutiny motionless; when she nodded, he led his horse beside hers without any more words of explanation. Her own mount became restive; she laid a restraining hand upon him, but said nothing. If the traveller had treachery in mind, she could match him.

They headed downhill, following the sun’s path; their shadows went before them, bluish and long. The day passed into afternoon, and eventually, in front of them, the sun engaged in battle. The blood lingered long on the clear horizon.

The stars were distinct when they stopped for the night. A small fire was all their concession to the season; both had often slept on bare ground. She was weary and would have been glad to have slipped into dreaming, but he stayed crosslegged, gazing at the heart of the flame; both manners and common sense required that she keep him company.

“I am a hunter,” he said after a long silence, “and a very good one. But my prey tonight is fey and deadly; what would you advise?” And as he raised his eyes to hers, she saw that they were now empty and reflecting the sky, and knew him.

“Well met, Lord,” she replied. “I should have known, when my horse shied. Why such excessive courtesy? You could have taken me any moment, in any way.”

“And insult your dignity?”

“I wish you hadn’t given me the choice… for I am very tired and would fain decline challenge.”

She stood up; he followed her. With a small sigh, she donned her weapons. They faced each other at a nearby oval stone plateau, which the glaciers had worn smooth. They bowed deeply, and engaged.

She was the best, even past her prime. But the other’s arm was of iron and each of his blows left blood behind, and merciless cold. Under the sliver of the late-rising moon she fought on, and her sword grew blunt; she threw it away and uncoiled her whip, holding the dagger in reserve.

He lowered his own weapon.

“You can stop now; I would be slain were I mortal. Surely honor is fully satisfied.”

She smiled and tried her whip against the wind; it was rising, heralding the sunrise.

They continued circling until the stars paled and a band of many colors appeared on the eastern horizon. Her whole body grew numb and her whip fell from her hand. As he raised his sword for the final thrust, she sank her own dagger to the hilt below her rib.

“I lived to see another dawn,” she whispered. “It is good that no stone will burden me. I will be able to stargaze; perhaps a tree will grow out of me… and the passing cranes will bring me tidings of the world.”

Related posts:

“As Weak as Women’s Magic”

Why I Won’t Be Taking the Joanna Russ Pledge

Who Will Be Companions to Female Kings?

The Persistent Neoteny of Science Fiction

Ain’t Evolvin’: The Cookie Cutter Self-Discovery Quest

Grandmothers Raise Civilizations

So, Where Are the Outstanding Women in X?

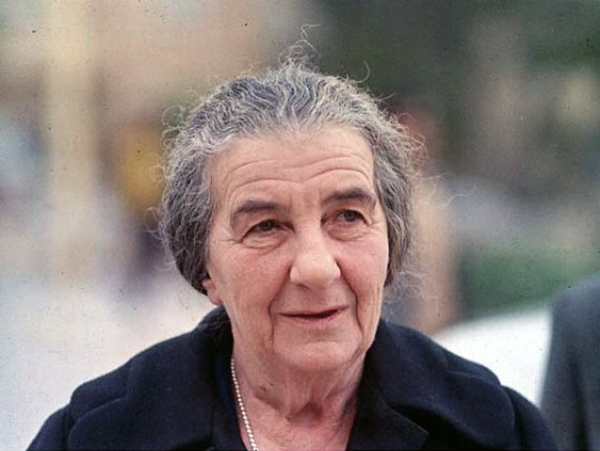

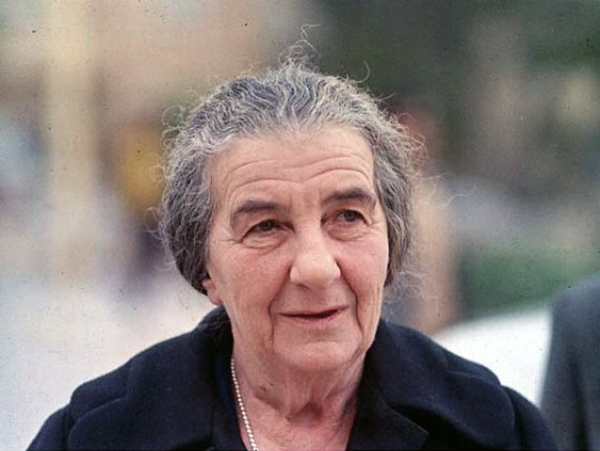

Images: Lady Lisa (Sandy Powers); Golda Meir, fourth prime minister of Israel (Associated Press); Ursula Burns, engineer, CEO of Xerox (Motoya Nakamura); Dr. Jill Tarter, astronomer, SETI pioneer (SETI Archive); Helen Mirren as Prosper@ in Julie Taymor’s The Tempest (Miramax)