The Persistent Neoteny of Science Fiction

Thursday, December 29th, 2011“Science fiction writers, I am sorry to say, really do not know anything. We can’t talk about science, because our knowledge of it is limited and unofficial, and usually our fiction is dreadful.”

When Margaret Atwood stated that she does not write science fiction (SF) but speculative literature, many SF denizens reacted with what can only be called tantrums, even though Atwood defined what she means by SF. Her definition reflects a wide-ranging writer’s wish not to be pigeonholed and herded into tight enclosures inhabited by fundies and, granted, is narrower than is common: it includes what I call Leaden Era-style SF that sacrifices complex narratives and characters to gizmology and Big Ideas.

When Margaret Atwood stated that she does not write science fiction (SF) but speculative literature, many SF denizens reacted with what can only be called tantrums, even though Atwood defined what she means by SF. Her definition reflects a wide-ranging writer’s wish not to be pigeonholed and herded into tight enclosures inhabited by fundies and, granted, is narrower than is common: it includes what I call Leaden Era-style SF that sacrifices complex narratives and characters to gizmology and Big Ideas.

By defining SF in this fashion, Atwood made an important point: Big Ideas are the refuge of the lazy and untalented; works that purport to be about Big Ideas are invariably a tiny step above tracts. Now before anyone starts bruising my brain with encomia of Huxley, Asimov, Stephenson or Stross, let’s parse the meaning of “a story of ideas”. Like the anthropic principle, the term has a weak and a strong version. And as with the anthropic principle, the weak version is a tautology whereas the strong version is an article of, well, religious faith.

The weak version is a tautology for the simplest of reasons: all stories are stories of ideas. Even terminally dumb, stale Hollywood movies are stories of ideas. Over there, if the filmmakers don’t bother with decent worldbuilding, dialogue or characters, the film is called high concept (high as in tinny). Other disciplines call this approach a gimmick.

The strong version is similar to supremacist religious faiths, because it turns what discerning judgment and common sense classify as deficiencies to desirable attributes (Orwell would recognize this syndrome instantly). Can’t manage a coherent plot, convincing characters, original or believable worlds, well-turned sentences? Such cheap tricks are for heretics who read books written in pagan tongues! Acolytes of the True Faith… write Novels of Ideas! This dogma is often accompanied by its traditional mate, exceptionalism – as in “My god is better than yours.” Namely, the notion that SF is intrinsically “better” than mainstream literary fiction because… it looks to the future, rather than lingering in the oh-so-prosaic present… it deals with Big Questions rather than the trivial dilemmas of ordinary humans… or equivalent arguments of similar weight.

I’ve already discussed the fact that contemporary SF no longer even pretends to deal with real science or scientific extrapolation. As I said elsewhere, I think that the real division in literature, as in all art, is not between genre and mainstream, but between craft and hackery. Any body of work that relies on recycled recipes and sequels is hackery, whether this is genre or mainstream (as just one example of the latter, try to read Updike past the middle of his career). Beyond these strictures, however, SF/F suffers from a peculiar affliction: persistent neoteny, aka superannuated childishness. Most SF/F reads like stuff written by and for teenagers – even works that are ostensibly directed towards full-fledged adults.

Now before the predictable shrieks of “Elitist!” erupt, let me clarify something. Adult is not a synonym for opaque, inaccessible or precious. The best SF is in many ways entirely middlebrow, as limpid and flowing as spring water while it still explores interesting ideas and radiates sense of wonder without showing off about either attribute. A few short story examples: Alice Sheldon/James Tiptree’s A Momentary Taste of Being; Ted Chiang’s The Story of Your Life; Ursula Le Guin’s A Fisherman of the Inland Sea; Joan Vinge’s Eyes of Amber. Some novel-length ones: Melissa Scott’s Dreamships; Roger Zelazny’s Jack of Shadows; C. J. Cherryh’s Downbelow Station; Donald Kingsbury’s Courtship Rite. Given this list, one source of the juvenile feel of most SF becomes obvious: fear of emotions; especially love in all its guises, including the sexual kind (the real thing, in its full messiness and glory, not the emetic glop that usurps the territory in much genre writing, including romance).

SF seems to hew to the long-disproved tenet that complex emotions inhibit critical thinking and are best left to non-alpha-males, along with doing the laundry. Some of this comes from the calvinist prudery towards sex, the converse glorification of violence and the contempt for sensual richness and intellectual subtlety that is endemic in Anglo-Saxon cultures. Coupled to that is the fact that many SF readers (some of whom go on to become SF writers) can only attain “dominance” in Dungeons & Dragons or World of Warcraft. This state of Peter-Pan-craving-comfort-food-and-comfort-porn makes many of them firm believers in girl cooties. By equating articulate emotions with femaleness, they apparently fail to understand that complex emotions are co-extensive with high level cognition.

SF seems to hew to the long-disproved tenet that complex emotions inhibit critical thinking and are best left to non-alpha-males, along with doing the laundry. Some of this comes from the calvinist prudery towards sex, the converse glorification of violence and the contempt for sensual richness and intellectual subtlety that is endemic in Anglo-Saxon cultures. Coupled to that is the fact that many SF readers (some of whom go on to become SF writers) can only attain “dominance” in Dungeons & Dragons or World of Warcraft. This state of Peter-Pan-craving-comfort-food-and-comfort-porn makes many of them firm believers in girl cooties. By equating articulate emotions with femaleness, they apparently fail to understand that complex emotions are co-extensive with high level cognition.

Biologists, except for the Tarzanist branch of the evo-psycho crowd, know full well by now that in fact cortical emotions enable people to make decisions. Emotions are an inextricable part of the indivisible unit that is the body/brain/mind and humans cannot function well without the constant feedback loops of these complex circuits. We know this from the work of António Damasio and his successors in connection with people who suffer neurological insults. People with damage to that human-specific newcomer, the pre-frontal cortex, often perform at high (even genius) levels in various intelligence and language tests – but they display gross defects in planning, judgment and social behavior. To adopt such a stance by choice is not a smart strategy even for hard-core social Darwinists, who can be found in disproportionate numbers in SF conventions and presses.

To be fair, cortical emotions may indeed inhibit something: shooting reflexes, needed in arcade games and any circumstance where unthinking execution of orders is desirable. So Galactic Emperors won’t do well as either real-life rulers or fictional characters if all they can feel and express are the so-called Four Fs that pass for sophistication in much of contemporary SF and fantasy, from the latest efforts of Iain Banks to Joe Abercrombie.

Practically speaking, what can a person do besides groan when faced with another Story of Ideas? My solution is to edit an anthology of the type of SF I’d like to read: mythic space opera, written by and for full adults. If I succeed and my stamina holds, this may turn into a semi-regular event, perhaps even a small press. So keep your telescopes trained on this constellation.

Note: This is part of a lengthening series on the tangled web of interactions between science, SF and fiction. Previous rounds: Why SF needs…

…science (or at least knowledge of the scientific process): SF Goes McDonald’s — Less Taste, More Gristle

…empathy: Storytelling, Empathy and the Whiny Solipsist’s Disingenuous Angst

…literacy: Jade Masks, Lead Balloons and Tin Ears

…storytelling: To the Hard Members of the Truthy SF Club

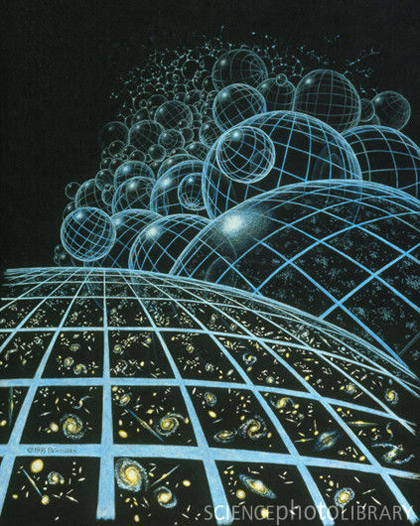

Images: 1st, Bill Watterson’s Calvin, who knows all about tantrums; 2nd, Dork Vader, an exemplar of those who tantrumize at Atwood; 3rd, shorthand vision of my projected anthology.