by Larry Klaes, space exploration enthusiast, science journalist, SF aficionado (plus a dissenting coda by Athena)

There is an interesting parallel between John Carter as the main character of the Mars series of adventure novels begun by Edgar Rice Burroughs (from here on called ERB) one century ago this year, and the recently released Disney film of the same name.

There is an interesting parallel between John Carter as the main character of the Mars series of adventure novels begun by Edgar Rice Burroughs (from here on called ERB) one century ago this year, and the recently released Disney film of the same name.

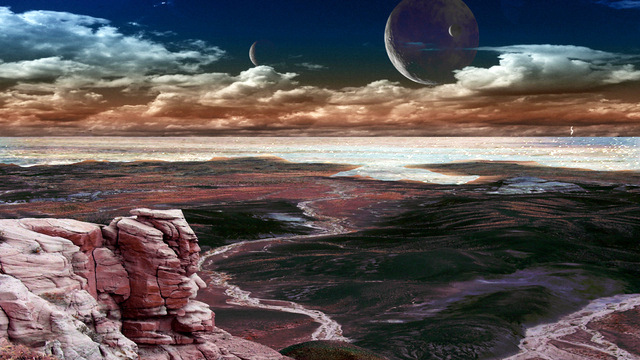

Both arrived on their respective worlds – the fictional man Carter on planet Mars, a.k.a. Barsoom, and the motion picture John Carter in cinemas all over planet Earth (a.k.a. Jarsoom) – with relatively little fanfare. Both Carters initially encountered natives who had no real idea who they were and were ready to kill them off. Yet somehow both survived their hostile environments and slowly earned the understanding and respect of their newfound worlds, eventually going on to change things for the better and having a wild time in the process.

Now of course the film version still has a long road ahead to achieve its equivalent of what the novel hero achieved in his fictional and serialized lifetime. To be honest, I do not know if it will ever become as popular and influential as the novels were in their day, if for no other reason than too many other fictional series influenced by the ERB works have left their much stronger mark on the cultural mindset in the intervening century. In addition, while John Carter is better than I feared, the very ironic fact that it looks rather derivative of the very genre it spawned may permanently hobble its journey across the cinematic and cultural landscape.

So why should I make a big deal out of a film and series that its parent company will probably write off as a financial loss, one that most of today’s audience is almost totally unfamiliar with, and in truth its core plot was not terribly original or new when ERB produced its first installment back in 1912?

For the following reasons: The film did not become the bloated mess that I thought Hollywood was going to turn it into (and which many film critics who I do not think would know or understand science fiction and its history if they proverbially bit them continue to insist it is while mentioning its big budget in the same breath). The John Carter series deserves to be honored, understood, and appreciated for all it has done both for science fiction/fantasy and for influencing later real scientists like Carl Sagan, who talked about his love for the series as a youth in an episode of Cosmos. Finally, the real story and history behind the influences – hinted at in the film – that spawned John Carter and affected our views of life on Mars and elsewhere are more than worthy of being reintroduced to new generations as well.

The plot of John Carter is essentially that of ERB’s first novel in the series, A Princess of Mars: Confederate war veteran and Gentleman of Virginia John Carter goes into a cave in the Southwestern United States and wakes up millions of miles away on the planet Mars. There he meets several of the remaining native populations on that world, all of whom are battling with each other and the elements as Mars is slowly drying up. Carter’s Earth-developed muscles allow him to jump quite high and punch very hard in the lower Martian gravity, abilities which quickly earn him the awe and respect of key natives. In the end, our hero defeats the bad guys, wins the hand of the beautiful Princess of Helium, Dejah Thoris, and then involuntarily ends up back on Earth. Carter spends most of his Jarsoomian exile trying to get back to Mars and his wife, which he eventually does.

I must confess: I did not read any of the John Carter novel series until rather recently, despite knowing about them for most of my life. I am not a big fan of fantasy fiction and that is what I considered these works to be. I also assumed that the prose would not have aged well in the intervening decades.

I have since read the first novel and, like the film, found it to be not as bad as I feared. Both were rather entertaining and I found myself actually caring about the characters, always a key point for me with any story. As just one example, I recall being both surprised and moved when it was revealed in the novel that Sola was the daughter of Tars Tarkas.

Based on past experience with Hollywood’s efforts at science fiction (and John Carter really is basically SF and not fantasy), along with Disney’s historical habit of making major changes in their productions to suit their intended audiences and their less-than-stellar promotional efforts for this film, I expected John Carter to be an expensive and flashy mess, one that was as much about the original A Princess of Mars as the “re-imaged/re-invented” Star Trek film from 2009 was about the original Star Trek television series: A shell resembling the franchise but full of hot air and junk underneath. Instead I witnessed a film that actually got the main characters and plot points, along with the essence and feel of the novel – no small feat there. I just wish that more people were aware of this and could appreciate it. Ironically, science fiction is starting to become more “acceptable” to the mainstream audience due to the reimaged Battlestar Galactica and especially The Hunger Games series, whose first film came out right after John Carter and financially steamrolled our Martian hero and every other current movie in its path.

I found the film to capture the feel and look of the novel as I and others imagined it quite well. From the flying battle cruisers to the appearance and behavior of the warrior Tharks, this cinematic world of Barsoom is one I think ERB would have said well matched his visions of his creation.

There were a few notable changes from the novel, most of which only make sense in light of the medium and era. One was the addition of clothing on John Carter and the residents of Barsoom. In the novel, most natives went either naked or nearly so and did not even think twice about being in such a state (Dejah Thoris only wore strategically-placed ornate jewelry, for example). John Carter even arrived on Mars sans clothing. For obvious reasons the film could not replicate this situation from the novel; besides, it probably would have been too distracting even if such a thing were allowed by the modern film industry.

The women of Barsoom fared rather well from their “modernization” in the film, though it should be noted that even in the first novel I did not find them to be just the damsels-in-distress one might be led to believe from the decades of artwork depicting that alien world.

The women of Barsoom fared rather well from their “modernization” in the film, though it should be noted that even in the first novel I did not find them to be just the damsels-in-distress one might be led to believe from the decades of artwork depicting that alien world.

The two main Martian city-states depicted in the film, Helium and Zodanga, employed female soldiers as readily as male ones. I had to wonder if this situation was due to the fact that the Martian environment was dying and people and resources were in ever-dwindling supply, but no one ever seemed to question or even react to the idea of women in their military. The audience was not given enough cinematic time to learn very much about these societies in any event.

The Thark Sola was an intelligent and compassionate individual in addition to being a strong warrior. She endured a fair deal of suffering from her harsh culture to remain true to herself and her beliefs. Sola also became open to new ideas as the story progressed, such as flying, despite her father and chief Tars Tarkas earlier intoning that “Tharks do not fly!”

The most notable woman of the series is of course Dejah Thoris. While she remained a beautiful princess and the focus of John Carter’s admiration and desire, for the film Dejah also became a highly capable scientist as well as a warrior who more than held her own in battle. When the Helium leadership was ready to cave in and acquiesce to the demands of the Zodanga leader to marry Dejah in the hope of saving their society from defeat and destruction, Dejah was the only one who not only balked at this forced union but saw how Helium’s being united with the more barbaric city-state of Zodanga would actually undermine her culture and eventually all the people of Barsoom.

Dejah’s demonstrated scientific knowledge and technical skills were strong enough that the main “bad guys” of the film, the highly advanced species known as the Thern, considered Dejah to be a serious impediment to their plans for Barsoom while simultaneously admiring her abilities. As for the actor who played the Princess of Helium, Lynn Collins was an excellent choice for the character. She not only played Dejah with both intelligence and an air of royal nobility, Collins’ years of martial arts training also showed convincingly in her numerous scenes of hand-to-hand combat – including the several occasions when Carter got behind Dejah for protection!

The Thern are another cinematic modification from the novel. In A Princess of Mars, Martian natives make a trip down the River Iss when they feel ready to pass on from this life. They believe at the end of that river is where they will meet the goddess Issus and go on to a paradisiacal afterlife. Instead the mythology and the journey are a trap set by the Thern, descendants of the White Martians, who use monstrous creatures such as the white apes to kill and eat the unwary pilgrims and enslave or consume in turn those who survive the ordeal.

In the film, the Thern are an advanced alien race (they appear as humanoids but can also shapeshift) who travel from one inhabited world to another and “feed” off the energies expended by the native populations as they struggle with each other and use up or neglect their planet’s natural resources. One Thern named Shang implies to Carter that Earth and humanity are next on their menu once they are done with the dying Barsoom.

The Thern have a very interesting and quite alien technology which looks like a tangled mass of blue fibers, whether it is one of their structures or a weapon (Dejah Thoris recognizes its artificial nature). They also travel between worlds by sending “copies” of themselves similar to a fax using a medallion that operates on specific verbal commands. Whereas in the novel, Carter mysteriously arrives on Mars after simply falling asleep in a cave, our hero is accidentally transported to Barsoom by Thern technology. While of course there is no actual explanation given as to how the mechanism works, the audience is at least handed some kind of plausible reason for Carter’s celestial journey that is no worse than using a faster-than-light drive for a fictional starship. Besides, the JC series is all about the destination, not the journey.

The film version of the Thern left me wondering if perhaps there are advanced societies in the galaxy who view other alien species as lesser creatures to either be ignored or utilized for their own purposes. While they held some genuine admiration for Dejah Thoris, I got the impression that their whole attitude about using Barsoom until it was dry and dead and all the other worlds they have come across could be summed up as “It’s nothing personal, it’s just business.”

I have often wondered if an advanced ETI, using the Kardashev Type 2 or 3 labels for simplification, would mow over whole worlds and species as they developed their interstellar existence in the same way a construction crew would run over an ant colony on their building site. I would like to think that such sophisticated and experienced beings would be a bit more sensitive than that, but we are still so very clueless about anyone else in the Milky Way galaxy and beyond.

Athena’s afterword: Unsurprisingly, my view of John Carter (henceforth JCM) is far more jaundiced than Larry’s. JCM is dull, curiously inert, with zero frisson or sensawunda despite the non-stop eye candy. Although the novel it’s based on predated and influenced Star Wars, Avatar, etc, it was a given that the film’s late arrival would doom it to looking stale unless its makers were truly bold. Pressing Pixar’s Stanton into service made success a possibility but Disney standard hackery prevailed: the deletion of crucial words from the film’s title (Mars, because other films with Mars in their titles bombed; Princess, because… it might give the film girl cooties) signals this fatal lack of conviction.

True, JCM is not a total failure; however, given its semi-infinite budget and the longueurs recognized even by its champions, this is a pathetically low bar. It’s a near-failure even as film space opera — which by tradition has low standards for coherence, opting instead for assaultive FX pyrotechnics. Of course, JCM’s science is non-existent even within its own silly framework (example: the intermittence and variability of Carter’s locust-like jumping abilities). At least, unlike Cameron’s Na’vi, Stanton forbore from putting breasts on female Tharks. In fact, JCM’s core failure lies in its clumsy, generic narrative and its paper-thin worldbuilding and characters, for whom it’s impossible to care. Additionally, by being mostly faithful to the novel, JCM’s makers reproduced its highly problematic underpinnings.

The cultures in JCM are based (snore) on ancient Rome and the Celtic and German nations that opposed it – as filtered through the lens of someone who learned history from comics or fifties Hollywood films. JCM’s obvious muscular-christian underdrone further underlines its poverty of imagination. There is no internal logic to the conflicts: they must simply exist, so that 1) we can see the neat-o flying machines and 2) the savior can become indispensable and lead his disciples to victory. Its pace is as lumbering as its six-legged war beasts; neither its tone nor its visuals ever coalesce. The relentless battles and fights are choppy and muddy. The dialogue is clunkier than that of Lucas (a feat I considered impossible), the characters look and speak like Pharaonic wooden statues and the two leads have as much chemistry as pet rocks. The aptly named Taylor Kitch, blander than lo-fat cottage cheese, doesn’t deserve Lynn Collins’ hot chili and the best that can be said about Thoris and Sola is that neither is a bimbo… or a blonde.

The clichés that literally sink JCM have dogged Hollywood space operas even in their self-labeled progressive incarnations like Star Trek: the White Messiah who out-natives the natives and has their princesses begging for his babbies; the lone feisty-but-feminine metal-bikini-clad woman among a sea (desert?) of men, bereft of any female interactions; the total absence of mothers, when even the non-dyadic Thark family structure gets twisted into providing Sola with a father; natives as noble savages who prevail, Ewok-like, over much superior technology once they choose the right (non-native) leader; hierarchical dog-eat-dog warrior societies; imperial rule by charismatic autocrats as the sole viable method of governance; the dog-like mascot whose sugary cuteness could elicit a full-blown diabetic coma.

People will undoubtedly try to argue that ERB was “a man of his time”. This is an excuse used ad nauseam for other SF/F “founders” such as Tolkien – who in fact was deemed a regressive throwback even by his own circle before he got canonized into infallibility by his acolytes. Ditto for ERB. As one example, John Carter is a “gentleman of Virginia” who served with distinction in the Confederate Army. Romantic lost causes aside, it means that ERB deliberately made his hero someone who chose to uphold the institution of slavery. And, of course, the names… oh, how they thud! Zodanga. Woola. Tardos Mors. Barsoom (rhymes with bazoom and va-va-voom, underscored by the Frazetta opulent pornokitch depictions so adored by Tarzanist evopsychos).

Such material can be salvaged in only two ways: either by radical re-imagining (which briefly was the route of the Battlestar Galactica reboot before it collapsed under its maker’s pretensions) or by being played as stylish high camp (which was why the Flash Gordon 1980 remake was such a breath of fresh air). Like a good bone structure underneath flesh gone to flab, there were glimpses of what might have been had Stanton and his paymasters been braver. But that would be a parallel universe where Barsoom truly came alive. Stanton tries to elicit extra sympathy (and remind us of Wall-E) by dedicating JCM to Steve Jobs – but his latest opus resembles a clunky, bloated Microsoft PC. It makes me once again think how immensely grateful I am that The Lord of the Rings was not directed by an American.

Images: John Carter (Taylor Kitch) realizing that not even super-jumping abilities will get him out of this mess; Dejah Thoris (Lynn Collins) all undressed up with nowhere to go; Dejah Thoris and John Carter trying to find escape clauses in their contracts; Sola (voiced by Samantha Morton) in WTF? posture.

Part 2

My article on junk DNA and the recent huge PR noise associated with it just appeared in Scientific American as a guest post. I will reprint it here toward the end of the week, to give SciAm its time lead.

My article on junk DNA and the recent huge PR noise associated with it just appeared in Scientific American as a guest post. I will reprint it here toward the end of the week, to give SciAm its time lead.