Eleven years ago, Harvard Alumni Magazine asked me why I wrote The Biology of Star Trek despite my lack of tenure. My answer was The Double Helix: Why Science Needs Science Fiction. In it, I described how science fiction can make science attractive and accessible, how it can fire up the dreams of the young and lead them to become scientists or, at least, explorers who aren’t content with canned answers.

The world has changed since then, the US more than most. American culture has always proclaimed its distrust of authority. However, the nation’s radical shift to the right also brought on disdain for all expertise – science in particular, as can be seen by the obstruction of research in stem cells and climate change and of teaching evolution in schools (to say nothing of scientist portrayals in the media, exemplified by Gaius Baltar in the aggressively regressive Battlestar Galactica reboot).

The world has changed since then, the US more than most. American culture has always proclaimed its distrust of authority. However, the nation’s radical shift to the right also brought on disdain for all expertise – science in particular, as can be seen by the obstruction of research in stem cells and climate change and of teaching evolution in schools (to say nothing of scientist portrayals in the media, exemplified by Gaius Baltar in the aggressively regressive Battlestar Galactica reboot).

This trend culminated in the choice of first a president and then a vice-presidential candidate who flaunted their ignorance and deemed their faux-folksy personae sufficient qualifications to lead the most powerful nation on the planet. Even as the fallout from these decisions deranges their culture, Americans cling to their iPods, SUVs and Xboxes and still expect instant cures for everything, from acne to old age, seeing scientists as the Morlocks that must cater to their Eloi.

Science fiction is really a mirror and weathervane of its era. So it comes as no surprise that the dominant tropes of contemporary speculative fiction reflect the malaise and distrust of science that has infected the Anglosaxon First World: cyberpunk and urban fantasy have their feet (and eyes) firmly on the ground. Space exploration is passé, and such luminaries as Charlie Stross delight in repeatedly “proving” that the only (straw)people to still contemplate crewed space travel are deluded naifs who can’t/won’t parse scientific facts or face unpalatable limitations.

I’ve been reading SF since the early seventies, ever since my English became sturdy enough to support the habit. In both reading and writing, I favor layered works that cross genre boundaries. This may explain why I have a hard time getting either inspired or published in today’s climate, in which publishers and readers alike demand “freshness” as long as it’s more of the same. Yet old fogey that I’m becoming, I do believe that people who write SF should have a nodding acquaintance with science principles and the scientific mindset.

I’ve been reading SF since the early seventies, ever since my English became sturdy enough to support the habit. In both reading and writing, I favor layered works that cross genre boundaries. This may explain why I have a hard time getting either inspired or published in today’s climate, in which publishers and readers alike demand “freshness” as long as it’s more of the same. Yet old fogey that I’m becoming, I do believe that people who write SF should have a nodding acquaintance with science principles and the scientific mindset.

So imagine my surprise when the following comment met with universal approval on a well-known SF blog: “There seems to be a common feeling with people coming into SF that you need to know real science to write good SF. Which is of course rubbish.”

Let me rewrite that statement for another genre: “There seems to be a common feeling with people coming into historical fiction that you need to know real history – or at least the history of the era you plan to portray – to write good historical fiction or alternative history. Which is of course rubbish.”

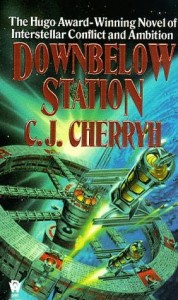

Cell phones in a Renaissance novel? Tudor court ladies on mopeds? Why should anyone notice or care? Likewise, “cracks” in the event horizon of a black hole? Instant effortless shapeshifting? Only an elitist jerk would object, spoiling the fun and causing unnecessary angst to the author! Never mind that such sloppiness jolts the reader out of the suspension of disbelief necessary for reading the story – and is particularly unpardonable because a passable veneer of knowledge can be readily acquired by surfing the Internet.

Many of today’s SF writers and readers don’t just proudly proclaim that they don’t know nuthin’ ‘bout no science; they also read only within ever-narrowing subgenres – and only contemporaries. When I attended an SF workshop supposedly second only to Clarion, a fellow participant castigated me for positing the “completely absurd” ability to record sounds off the grooves of a ceramic surface. Of course, this is essentially a variation of sound reproduction in phonographic records. No wonder that much of contemporary speculative fiction tastes like recycled watery gruel or reheated corn syrup.

Please understand, I don’t miss the turgid exposition, cardboard-thin characters and blatant sexism, parochialism and triumphalism of the Leaden… er, Golden Era of SF (though the same types of attributes and attitudes have resurfaced wholesale in cyberpunk). My lodestars are Le Guin, Tiptree, Anderson, Zelazny, Butler, Cherryh, Scott – and Atwood, despite her protestations that she does not, repeat not, write science fiction. They all prove that top-notch SF can incorporate gendanken experiments that contravene physical laws: FTL travel, stable wormholes, mind uploading, a multiplicity of genders and earth-like planets, anthropomorphic aliens, to name only a few.

Please understand, I don’t miss the turgid exposition, cardboard-thin characters and blatant sexism, parochialism and triumphalism of the Leaden… er, Golden Era of SF (though the same types of attributes and attitudes have resurfaced wholesale in cyberpunk). My lodestars are Le Guin, Tiptree, Anderson, Zelazny, Butler, Cherryh, Scott – and Atwood, despite her protestations that she does not, repeat not, write science fiction. They all prove that top-notch SF can incorporate gendanken experiments that contravene physical laws: FTL travel, stable wormholes, mind uploading, a multiplicity of genders and earth-like planets, anthropomorphic aliens, to name only a few.

Fiction must be the dominant partner in all literary efforts. Imaginative storytelling trumps strict scientific accuracy. Nevertheless, SF requires convincing, consistent worldbuilding. This in turn demands that the author stick to the rules s/he has made and that the premises adhere to known laws once the speculative exceptions have been accommodated: if a planet is within a red dwarf sun’s habitable zone, its orbit has to be tidally locked barring incredibly advanced technology. If a story contravenes or doesn’t depend on science, real or speculative, it’s not SF. It’s magic realism or fantasy. Not that it matters, as long as the plot and characters are compelling.

Avast, Impudent Cooties!

There have been recent lamentations within the tribe about SF losing ground to fantasy, horror and other “lesser” cousins. Like all niche genres, speculative fiction further marginalizes itself by creating arbitrary hierarchies that purport to reflect intrinsic worth but in fact enshrine unexamined cultural values: hardcover self-labeled hard SF preens at the top, written mostly by boys for boys; print-on-demand SF romance skulks at the bottom, written almost exclusively by girls for girls (though the increasing proportion of female readership is exerting significant pressure on the pink ghetto walls).

The real problem is not that science is hard to portray well in SF. The problem is impoverished imagination, willful ignorance and endless repetition of recipes. In short: failure of nerve. Great SF stories are inseparable from the science in them. A safe, non-demanding story is unlikely to linger in the readers’ memory or elicit changes in their thinking.

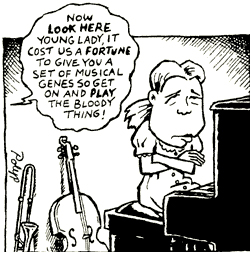

If science disappears altogether from SF or survives only as the gimmick that allows “magic” plot outcomes, SF will lose its greatest and unique asset: acting as midwife and mentor to future scientists. This is no mere intellectual exercise for geeks. To give one example, mental and physical work on the arcships so denigrated by Stross et al. would also help us devise solutions to the inexorable looming specter of finite terrestrial resources.

Rick Sternbach: Solar Sail

The political and social pseudo-pieties of the US cost it several generations of scientists, some in their prime. The full repercussions won’t appear immediately, but already the US is no longer the uncontested forerunner in science and technology and its standard of living is dropping accordingly. Breakthroughs in physics and biology are happening elsewhere. Of course, all empires have a finite lifespan. Perhaps the time has come for the Chinese or the Indians to lead. But no matter who is the first among equals in the times to come, I stand by the last sentence in my Double Helix essay: “Though science will build the starships, science fiction will make us want to board them.”

Update 1: Huffington Post just re-posted this article (without the accompanying images, though, which add texture to the story).

Update 2: The article is now also on the new blog I Like a Little Science in My Fiction.

There have been many branches on the hominid tree, but now a lone species walks the earth. We had company once, though, at least in Europe and West Asia – the Neanderthals.

There have been many branches on the hominid tree, but now a lone species walks the earth. We had company once, though, at least in Europe and West Asia – the Neanderthals.

James Cameron made two films that are high on my list of favorites: Terminator 2 and Aliens – not least because powerful women are central to the stories (even though he gave them the most conservative and clichéd motivation for heroism: maternal protectiveness). He was a taut, visually inventive storyteller once. But all his films after The Abyss increasingly resemble the Hindenburg: bloated, self-indulgent, lacking originality and subtlety in all but F/X.

James Cameron made two films that are high on my list of favorites: Terminator 2 and Aliens – not least because powerful women are central to the stories (even though he gave them the most conservative and clichéd motivation for heroism: maternal protectiveness). He was a taut, visually inventive storyteller once. But all his films after The Abyss increasingly resemble the Hindenburg: bloated, self-indulgent, lacking originality and subtlety in all but F/X. There’s nothing wrong with adults enjoying Disney-level spectacle, as long as they don’t make it their moral, intellectual or esthetic measuring stick. An artist with Cameron’s credibility and clout should undertake real challenges that inspire our innate desire to explore instead of recycling militaristic violence porn and preachy feel-good platitudes. He did it incredibly well before, he can do it again. And some childish dreams should remain dreams. They work far better as beckoning beacons.

There’s nothing wrong with adults enjoying Disney-level spectacle, as long as they don’t make it their moral, intellectual or esthetic measuring stick. An artist with Cameron’s credibility and clout should undertake real challenges that inspire our innate desire to explore instead of recycling militaristic violence porn and preachy feel-good platitudes. He did it incredibly well before, he can do it again. And some childish dreams should remain dreams. They work far better as beckoning beacons. The world has changed since then, the US more than most. American culture has always proclaimed its distrust of authority. However, the nation’s

The world has changed since then, the US more than most. American culture has always proclaimed its distrust of authority. However, the nation’s  I’ve been reading SF since the early seventies, ever since my English became sturdy enough to support the habit. In both reading and writing, I favor layered works that

I’ve been reading SF since the early seventies, ever since my English became sturdy enough to support the habit. In both reading and writing, I favor layered works that  Please understand, I don’t miss the turgid exposition, cardboard-thin characters and blatant sexism, parochialism and triumphalism of the Leaden… er, Golden Era of SF (though the same types of attributes and attitudes have resurfaced wholesale in cyberpunk). My lodestars are Le Guin, Tiptree, Anderson, Zelazny, Butler, Cherryh, Scott – and Atwood, despite her protestations that she does not, repeat not, write science fiction. They all prove that top-notch SF can incorporate gendanken experiments that contravene physical laws: FTL travel, stable wormholes, mind uploading, a multiplicity of genders and earth-like planets, anthropomorphic aliens, to name only a few.

Please understand, I don’t miss the turgid exposition, cardboard-thin characters and blatant sexism, parochialism and triumphalism of the Leaden… er, Golden Era of SF (though the same types of attributes and attitudes have resurfaced wholesale in cyberpunk). My lodestars are Le Guin, Tiptree, Anderson, Zelazny, Butler, Cherryh, Scott – and Atwood, despite her protestations that she does not, repeat not, write science fiction. They all prove that top-notch SF can incorporate gendanken experiments that contravene physical laws: FTL travel, stable wormholes, mind uploading, a multiplicity of genders and earth-like planets, anthropomorphic aliens, to name only a few.

I don’t know if any of these novels will ever get published. But these two green shoots have given me great joy and hope. It was my tremendous luck to have devoted friends who urged me to keep writing the saga; to meet Kay Holt and Bart Leib whose vision of Crossed Genres focused exactly on hard-to-categorize works like mine; and to enjoy the unwavering certainty of Peter Cassidy, who’s convinced that one day the entire saga will emerge from its cocoon and unfurl its wings. Dhi kéri ten sóran, iré ketháni.

I don’t know if any of these novels will ever get published. But these two green shoots have given me great joy and hope. It was my tremendous luck to have devoted friends who urged me to keep writing the saga; to meet Kay Holt and Bart Leib whose vision of Crossed Genres focused exactly on hard-to-categorize works like mine; and to enjoy the unwavering certainty of Peter Cassidy, who’s convinced that one day the entire saga will emerge from its cocoon and unfurl its wings. Dhi kéri ten sóran, iré ketháni.

When I belonged to several forums, my head resembled a gull rookery, awash with noise, random peckings and guano. Facebook was by far the worst offender, even after I ruthlessly pruned my friends list to a quarter of its size. And trying to reason with loud ill-informed semi-illiterates on scientific or political threads got tedious, sort of like having to handle teenagers who seriously think they’re the first and only ones to discover — nay, invent — sex.

When I belonged to several forums, my head resembled a gull rookery, awash with noise, random peckings and guano. Facebook was by far the worst offender, even after I ruthlessly pruned my friends list to a quarter of its size. And trying to reason with loud ill-informed semi-illiterates on scientific or political threads got tedious, sort of like having to handle teenagers who seriously think they’re the first and only ones to discover — nay, invent — sex. many thoughtful, thought-provoking comments; it also attracted commenters who objected strenuously to the article without having read it. Some brandished Star Trek, The Matrix and Kurzweil’s Singularity at me as science textbooks (or gospels, take your pick).

many thoughtful, thought-provoking comments; it also attracted commenters who objected strenuously to the article without having read it. Some brandished Star Trek, The Matrix and Kurzweil’s Singularity at me as science textbooks (or gospels, take your pick). As a companion piece to Calvin’s

As a companion piece to Calvin’s  Update 1: They say good things come in threes. When I got home tonight, I found a surprise package: Jack McDevitt’s just-released novel,

Update 1: They say good things come in threes. When I got home tonight, I found a surprise package: Jack McDevitt’s just-released novel,  One of the earliest and most lasting narrative models in science fiction is Frankenstein. The recent SciFi channel reboot of Battlestar Galactica owes itself as much to Mary Shelley as to the original 1978 television series. In the original, the robotic Cylons are creations and inheritors of a now-extinct reptilian race; in the 2003 reboot, the Cylons are our own creation. Like Frankenstein’s creature (in the novel), the reimagined Cylons are as capable of tormented philosophical reasoning as they are of homicidal rage.

One of the earliest and most lasting narrative models in science fiction is Frankenstein. The recent SciFi channel reboot of Battlestar Galactica owes itself as much to Mary Shelley as to the original 1978 television series. In the original, the robotic Cylons are creations and inheritors of a now-extinct reptilian race; in the 2003 reboot, the Cylons are our own creation. Like Frankenstein’s creature (in the novel), the reimagined Cylons are as capable of tormented philosophical reasoning as they are of homicidal rage. nt writing and acting, but by the final season Battlestar Galactica (or BSG to its friends) deteriorated into a self-parodying soap opera. We were told at the beginning of episodes that the Cylons “have a plan,” but it became increasingly clear that creator Ron Moore was making it up as he went along; by the series finale he had written the reboot’s most compelling creation, Kara “Starbuck” Thrace, into such a corner that he could only end her story by having her melt into the wind like an bad odor.

nt writing and acting, but by the final season Battlestar Galactica (or BSG to its friends) deteriorated into a self-parodying soap opera. We were told at the beginning of episodes that the Cylons “have a plan,” but it became increasingly clear that creator Ron Moore was making it up as he went along; by the series finale he had written the reboot’s most compelling creation, Kara “Starbuck” Thrace, into such a corner that he could only end her story by having her melt into the wind like an bad odor. Caprica is far better than The Phantom Menace, but that is a low bar, and neither is Caprica as compelling as the opening Battlestar Galactica miniseries. We are supposed to sympathize with Zoe’s grieving father, a Bill Gates-like character, but his distance from wife and work also distances him from the audience. Much more intriguing is Joseph Adams, a well-dressed lawyer who lost his wife and daughter in the same bombing that killed Zoe, and who is attempting to reconnect with his young son William, all the while in a dangerous dance with a Mafia-like gang from his Tauron homeworld. Young William, of course, grows up to be Bill Adama, who helps to save the human race 58 years later as captain of the Galactica. The Adama drama is much more compelling than the dull Frankenstein, I mean Greystone, family but is curiously underplayed here despite a few dramatic scenes.

Caprica is far better than The Phantom Menace, but that is a low bar, and neither is Caprica as compelling as the opening Battlestar Galactica miniseries. We are supposed to sympathize with Zoe’s grieving father, a Bill Gates-like character, but his distance from wife and work also distances him from the audience. Much more intriguing is Joseph Adams, a well-dressed lawyer who lost his wife and daughter in the same bombing that killed Zoe, and who is attempting to reconnect with his young son William, all the while in a dangerous dance with a Mafia-like gang from his Tauron homeworld. Young William, of course, grows up to be Bill Adama, who helps to save the human race 58 years later as captain of the Galactica. The Adama drama is much more compelling than the dull Frankenstein, I mean Greystone, family but is curiously underplayed here despite a few dramatic scenes.

I saw District 9 yesterday. This gory bore won an 88% rating at the Tomatometer? As well as rave reviews from intelligent, well-educated people across the age spectrum? Once again, as with

I saw District 9 yesterday. This gory bore won an 88% rating at the Tomatometer? As well as rave reviews from intelligent, well-educated people across the age spectrum? Once again, as with  The cruelties of segregation, the plight of refugees, our treatment of Others — those are burning subjects. So is the question of how we would interact with sentient aliens. None of them gets real treatment here. Instead, the film manipulates its viewers into feeling virtuous by being superficially “daring”. District 9 is neither science fiction nor social commentary; it’s violence porn — or, as producer Peter Jackson himself called it on io9, splatstick.

The cruelties of segregation, the plight of refugees, our treatment of Others — those are burning subjects. So is the question of how we would interact with sentient aliens. None of them gets real treatment here. Instead, the film manipulates its viewers into feeling virtuous by being superficially “daring”. District 9 is neither science fiction nor social commentary; it’s violence porn — or, as producer Peter Jackson himself called it on io9, splatstick. Several decades ago, James Tiptree Jr. (Alice Sheldon) wrote a story in which aliens eyeing the lush terrestrial real estate introduce something in the water or the air that makes men kill women and girls systematically, rather than in the usual haphazard fashion. Recent events have made me wonder if a milder version of Tiptree’s

Several decades ago, James Tiptree Jr. (Alice Sheldon) wrote a story in which aliens eyeing the lush terrestrial real estate introduce something in the water or the air that makes men kill women and girls systematically, rather than in the usual haphazard fashion. Recent events have made me wonder if a milder version of Tiptree’s  Of course, parity is not even remotely demanded — a mere one or two representatives often suffice as a sop (to such lows have we fallen). The bleatings about qualifications and tokenism are absurd, given the vast, stellar non-male non-white talent pool. The excuses sound even lamer (if not malicious) when one scans the predictable, often mediocre, rolodex-friend picks actually made in cases 1 and 2 above… and in more instances than I care to recall at other times.

Of course, parity is not even remotely demanded — a mere one or two representatives often suffice as a sop (to such lows have we fallen). The bleatings about qualifications and tokenism are absurd, given the vast, stellar non-male non-white talent pool. The excuses sound even lamer (if not malicious) when one scans the predictable, often mediocre, rolodex-friend picks actually made in cases 1 and 2 above… and in more instances than I care to recall at other times.

A recent entry by Mike Treder at the IEET site (Institute of Ethics and Emerging Technologies)

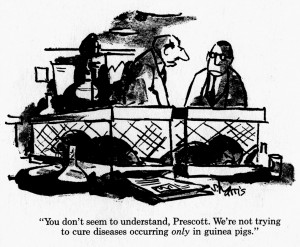

A recent entry by Mike Treder at the IEET site (Institute of Ethics and Emerging Technologies)  About a week ago, the Internet went wild with the announcement that a “fountain of youth” drug had been found that extends life by about 10%. I picked a site at random and read the report, knowing full well what I would find buried somewhere in the story. Sure enough, there it was, tucked at the end of a paragraph halfway down: the study was done on mice.

About a week ago, the Internet went wild with the announcement that a “fountain of youth” drug had been found that extends life by about 10%. I picked a site at random and read the report, knowing full well what I would find buried somewhere in the story. Sure enough, there it was, tucked at the end of a paragraph halfway down: the study was done on mice.

Yours truly

Yours truly  Alan Sokal was a teaching assistant in my quantum mechanics (QM) course. I still recall vividly the day he came with a graph showing the spike of the first-ever observed strange particle. I remember, too, the playful twinkle in his eye. Thirteen years ago, Alan (at this point a physics professor at NYU) submitted a paper to the prominent cultural studies journal Social Text, titled “Transgressing the Boundaries: Towards a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity”.

Alan Sokal was a teaching assistant in my quantum mechanics (QM) course. I still recall vividly the day he came with a graph showing the spike of the first-ever observed strange particle. I remember, too, the playful twinkle in his eye. Thirteen years ago, Alan (at this point a physics professor at NYU) submitted a paper to the prominent cultural studies journal Social Text, titled “Transgressing the Boundaries: Towards a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity”.

I like the aesthetics of Zen Buddhism very much. However, there is nothing to attract me in the religion’s misogyny (women cannot become Buddhas and must be reborn as men to attain Nirvana), its primitive cosmology of universe-toting turtles, its punitive stance that suffering is the result of bad past karma, its oppressive policies whenever it gained temporal power (including pre-Chinese Tibet, which was a far cry from Shangri-La) or the dog-like master/disciple formula that I dissected in my

I like the aesthetics of Zen Buddhism very much. However, there is nothing to attract me in the religion’s misogyny (women cannot become Buddhas and must be reborn as men to attain Nirvana), its primitive cosmology of universe-toting turtles, its punitive stance that suffering is the result of bad past karma, its oppressive policies whenever it gained temporal power (including pre-Chinese Tibet, which was a far cry from Shangri-La) or the dog-like master/disciple formula that I dissected in my  crystal domes, or as incandescent engines that create life? Science needs no pious platitudes or sloppy metaphors. Science doesn’t strip away the grandeur of the universe; the intricate patterns only become lovelier as more keep appearing and coming into focus. Science leads to connections across scales, from universes to quarks. And we, with our ardent desire and ability to know ever more, are lucky enough to be at the nexus of all this richness.

crystal domes, or as incandescent engines that create life? Science needs no pious platitudes or sloppy metaphors. Science doesn’t strip away the grandeur of the universe; the intricate patterns only become lovelier as more keep appearing and coming into focus. Science leads to connections across scales, from universes to quarks. And we, with our ardent desire and ability to know ever more, are lucky enough to be at the nexus of all this richness.