Lab Rat Cinema: Monetizing the Reptile Brain

Monday, January 11th, 2010“And the madness of the crowd is an epileptic fit.”

Tom Waits, In the Colosseum

Like anyone who didn’t greet Cameron’s Avatar as The Second Coming, I received predictable responses to my review. Some brave souls were relieved to hear they were not alone in perceiving that the Emperor wore slinky glittery togs but was nevertheless drooling. The percentage of these was higher than I expected, which made me hopeful that humanity may achieve long-term survival without regressing to a resemblance of the Flintstone cartoons.

Like anyone who didn’t greet Cameron’s Avatar as The Second Coming, I received predictable responses to my review. Some brave souls were relieved to hear they were not alone in perceiving that the Emperor wore slinky glittery togs but was nevertheless drooling. The percentage of these was higher than I expected, which made me hopeful that humanity may achieve long-term survival without regressing to a resemblance of the Flintstone cartoons.

Some insisted that I didn’t get Avatar’s subtle environment- and native culture-friendly message because I’m a jaded cynic out of touch with cosmic harmonies. These are probably the same people who think that positive thinking cures cancer (addressed sharply – in both senses – by Barbara Ehrenreich in her recent book Bright-Sided). I’ll believe the authenticity of their starry-eyedness when they sell their iPods and SUVs and give the proceeds to the residents of the Pine Ridge reservation. On the opposite end of the spectrum, a few called Avatar traitorous liberal propaganda, demonstrating their terminal lack of grasp on concepts. But then, what can one expect of people who voluntarily called themselves teabaggers?

Several exhorted me to “lighten up, it’s only a movie, can’t you stop thinking and just have fun?” This demand is the traditional ploy when someone can’t marshal a real argument – which is one reason why it’s routinely used on inconveniently uppity Others (see Me Tarzan, You Ape for a longer explanation). Them I will leave to the tender ministrations of Moff’s Law, with the added footnote that it’s actually impossible to turn a brain off, short of irreversible coma or death.

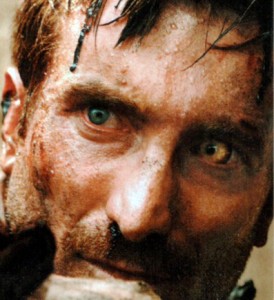

Finally, which brings me to this article’s subject, the fanboys shrieked “Die, heretic scum!” Those were hilarious, particularly the ones that pointed out my total ignorance of biology and referred me to the Pandorapedia (no link to this, since I won’t promote brain softening). I was tempted to leave them to their wet fantasies in their parents’ basements. However, inchoate rage of the Incredible Hulk variety is becoming increasingly prevalent in this culture and it extends far beyond the multiplex. I’ve dubbed it the Waterworld Syndrome, because I first articulated it after watching that horrible mess – a movie only in name, but in fact a relentless audiovisual battering.

The unmistakable sign of a well-wrought book or film is that it puts us in a light trance, emphasis on “light”. We suspend disbelief, immerse ourselves in the universe unfolding before us. Yet we don’t become passive vessels. Large parts of our brain stay busy evaluating the originality and quality of the worldbuilding, the consistency of the plot, the authenticity of the dialogue and characters. If anything jolts us out of this trance, the work immediately becomes as enticing as a flaccid balloon.

Hollywood directors have decided they don’t want to work on any of these aspects. They go through perfunctory motions, relying on lazy shorthand and recycled clichés, while they put their real effort in milking profits from the lunch boxes and video games based on their movies. This is not surprising: many started and/or double as directors for television commercials. Straightforward product placement has become ever more prominent in movies, especially those aimed at younger viewers – which at this point means almost all of them. Focus groups that now routinely “pre-test” movies have removed any pretense that film making is the craft of illuminating narratives that must be told. It’s all about marketing the franchises.

But movies still need to achieve that trance, because viewers are not so zombified as to stop thinking altogether (see note about coma above). Also, directors want a movie to leave enough of an impression that people will buy the associated tchotchkes. So they resort to the Waterworld technique, which consists of arousing the fight-or-flight reflex by sensory overload. In short, they use assaultive special effects. Today’s blockbuster movies, numbingly sequelized, are members of the Doom or Wolfenstein gang, except that they enforce even more passivity than the minimal act of frantically pushing the buttons of an XBox.

The fight-or-flight reflex is an ancient survival mechanism we share with other organisms that have a complex nervous system. Once the reflex is triggered, adrenaline and cortisol spike, the heart rate goes up, the blood supply gets diverted from the viscera and brain to the muscles, glucose floods the body, thinking is suppressed and we tremble and sweat like a beaten horse. On the behavioral side, the result is anger and fear that bypass our cortex, eluding conscious control. This makes perfect sense as a prelude to action when the trigger is legitimate: if we spend too much time analyzing the possible outcomes of a tiger’s appearance, we may end up in its stomach.

Sudden loud noises, abrupt luminosity changes, rapid irregular motion and objects fast growing in your visual field are among the triggers of fight-or-flight. Sound familiar? 3-D effects that force us to constantly flinch away from looming fronds or asteroids; car chases at a speed that our eyes can barely track; explosions, in-your-face gunshots and loud percussive soundtracks that make us jump – these are the common, blunt weapons in today’s blockbuster movie arsenal, aimed to jangle and pummel our brain into reflex mode.

Sudden loud noises, abrupt luminosity changes, rapid irregular motion and objects fast growing in your visual field are among the triggers of fight-or-flight. Sound familiar? 3-D effects that force us to constantly flinch away from looming fronds or asteroids; car chases at a speed that our eyes can barely track; explosions, in-your-face gunshots and loud percussive soundtracks that make us jump – these are the common, blunt weapons in today’s blockbuster movie arsenal, aimed to jangle and pummel our brain into reflex mode.

When fight-or-flight is triggered while someone is in a theater seat, the resulting anger and fear are not expended because there’s no action possible beyond chewing one’s popcorn faster. The stress hormones linger, and so do the emotions they arouse – displaced, unfocused, free-floating, ready for use by demagogues and charlatans. Objectively, it’s a terrific use of the misnamed reptile brain, much better than the subliminal messages they used to flash between frames in older movies. The behavioral conditioning is now integrated into the experience. And moviegoers, stunned into sullen docility, their brain chemistry cleverly subverted, increasingly expect visceral punches instead of stories, willingly collaborating in their own mental and emotional debasement.

People who crave such entertainment turn into mobs far more readily than those who demand less crude fare and will not abandon the prerogative of critical thought. The primitive worldview fostered by such abusive spectacle diverts people from trying to solve problems rationally, making it easier to belittle knowledge and expertise, cede rights and liberties and scapegoat marginalized groups and the unlucky – which by now include much of what was once the middle class.

If you think this is hyperbole, consider that Antonin Scalia used the TV show 24 as an authority for legitimizing the use of torture. The excuse that mindless entertainment relieves pressure at times of individual and collective stress is dangerous. It’s crucial to act as full humans not when times are easy, but when times are hard; when circumstances are best served by reflection, not reflex.

If you think this is hyperbole, consider that Antonin Scalia used the TV show 24 as an authority for legitimizing the use of torture. The excuse that mindless entertainment relieves pressure at times of individual and collective stress is dangerous. It’s crucial to act as full humans not when times are easy, but when times are hard; when circumstances are best served by reflection, not reflex.

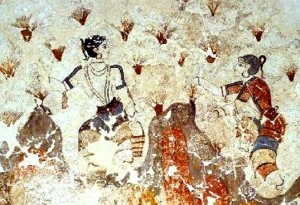

Images: 1st, Trey Parker & Matt Stone, South Park; 2nd, Louis Leterrier, The Incredible Hulk; 3rd, Stanley Kubrick, Clockwork Orange; 4th, John LeFrançois, Furious George.

Related articles:

Avatar: Jar Jar Binks Meets Pocahontas

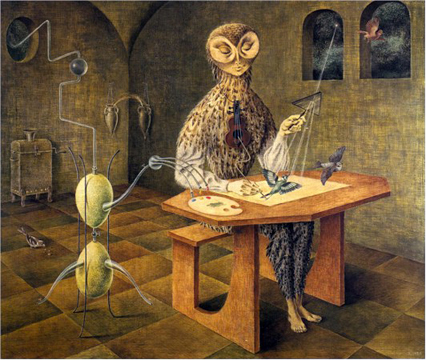

The Andreadis Unibrow Theory of Art

I don’t know if any of these novels will ever get published. But these two green shoots have given me great joy and hope. It was my tremendous luck to have devoted friends who urged me to keep writing the saga; to meet Kay Holt and Bart Leib whose vision of Crossed Genres focused exactly on hard-to-categorize works like mine; and to enjoy the unwavering certainty of Peter Cassidy, who’s convinced that one day the entire saga will emerge from its cocoon and unfurl its wings. Dhi kéri ten sóran, iré ketháni.

I don’t know if any of these novels will ever get published. But these two green shoots have given me great joy and hope. It was my tremendous luck to have devoted friends who urged me to keep writing the saga; to meet Kay Holt and Bart Leib whose vision of Crossed Genres focused exactly on hard-to-categorize works like mine; and to enjoy the unwavering certainty of Peter Cassidy, who’s convinced that one day the entire saga will emerge from its cocoon and unfurl its wings. Dhi kéri ten sóran, iré ketháni. I saw District 9 yesterday. This gory bore won an 88% rating at the Tomatometer? As well as rave reviews from intelligent, well-educated people across the age spectrum? Once again, as with

I saw District 9 yesterday. This gory bore won an 88% rating at the Tomatometer? As well as rave reviews from intelligent, well-educated people across the age spectrum? Once again, as with  The cruelties of segregation, the plight of refugees, our treatment of Others — those are burning subjects. So is the question of how we would interact with sentient aliens. None of them gets real treatment here. Instead, the film manipulates its viewers into feeling virtuous by being superficially “daring”. District 9 is neither science fiction nor social commentary; it’s violence porn — or, as producer Peter Jackson himself called it on io9, splatstick.

The cruelties of segregation, the plight of refugees, our treatment of Others — those are burning subjects. So is the question of how we would interact with sentient aliens. None of them gets real treatment here. Instead, the film manipulates its viewers into feeling virtuous by being superficially “daring”. District 9 is neither science fiction nor social commentary; it’s violence porn — or, as producer Peter Jackson himself called it on io9, splatstick. A story of mine,

A story of mine,

Two years ago, cancer struck me out of the clear blue sky at a moment in my life when I was gathering my strength for relaunching my research. I had just received two very hard-won grants after a lapse in funding that had essentially closed down my lab. The disease was at its early stages and I was spared the agony of chemotherapy, although some after-effects of the surgery (most prominently, severe fibromyalgia) are still with me.

Two years ago, cancer struck me out of the clear blue sky at a moment in my life when I was gathering my strength for relaunching my research. I had just received two very hard-won grants after a lapse in funding that had essentially closed down my lab. The disease was at its early stages and I was spared the agony of chemotherapy, although some after-effects of the surgery (most prominently, severe fibromyalgia) are still with me. I don’t believe in gods or an afterlife. Yet perhaps the only myth that can sustain us in such circumstances is Poul Anderson’s of the Ythrian Hunter God, a story that the medieval Greeks also told in their folksongs of Dighenís Akrítas: The Hunter will always prevail. The only thing you can do is give him a good hunt, for your own honor if not for his. Keep as much of your self and your life intact as long as you can. And do what you can to be long remembered, to leave that tiny footprint in the sand that will eventually get filled and smoothed away by the tide.

I don’t believe in gods or an afterlife. Yet perhaps the only myth that can sustain us in such circumstances is Poul Anderson’s of the Ythrian Hunter God, a story that the medieval Greeks also told in their folksongs of Dighenís Akrítas: The Hunter will always prevail. The only thing you can do is give him a good hunt, for your own honor if not for his. Keep as much of your self and your life intact as long as you can. And do what you can to be long remembered, to leave that tiny footprint in the sand that will eventually get filled and smoothed away by the tide.

So there I was, bright, science-oriented, competitive, unfeminine, demanding equal treatment, expecting my future partners to be both lovers and friends… blessed, too (or should it be cursed?) with my father’s unstinting love, as well as his frank appetites and eye for beauty in everything. Glumly contemplating the thorny path before me, I frequently complained to him for bequeathing the wrong chromosome to the zygote that produced me. A pragmatic man with a strong streak of defiant aloneness, he was unrepentant. The fourth of five brothers with no sister, he was ecstatic that his single child was a daughter to whom he could give the name of the mother they lost too early in a terrible accident – even though he had to fight with the priests, because the name was pagan (there was no separation of church and state in Greece at that time).

So there I was, bright, science-oriented, competitive, unfeminine, demanding equal treatment, expecting my future partners to be both lovers and friends… blessed, too (or should it be cursed?) with my father’s unstinting love, as well as his frank appetites and eye for beauty in everything. Glumly contemplating the thorny path before me, I frequently complained to him for bequeathing the wrong chromosome to the zygote that produced me. A pragmatic man with a strong streak of defiant aloneness, he was unrepentant. The fourth of five brothers with no sister, he was ecstatic that his single child was a daughter to whom he could give the name of the mother they lost too early in a terrible accident – even though he had to fight with the priests, because the name was pagan (there was no separation of church and state in Greece at that time). A scholarly essay must, of course, give examples… and not surprisingly, I didn’t find obvious snacho candidates among most mainstream fiction. But I can name a few in science fiction: Dominic Harlech, aka Niki Falcon in Emma Bull’s Falcon; Radu Drac in Vonda McIntyre’s Aztecs and Superluminal; the Servitors in Sheri Tepper’s The Gate to Women’s Country – who turn out to be the real men, rather than the so-called Warriors. And off the top of my head, I can think of four in film: Trevor Goodchild (Marton Csokas) in the film version of Aeon Flux; Sam Gillen (Jean Claude van Damme, who would have thunk!) in Nowhere to Run; Rob Roy McGregor (Liam Neeson) in Rob Roy; and, of course, Hawkeye (Daniel Day-Lewis) in The Last of the Mohicans. In that film, what pinpoints him as the quintessence of snachismo is not his undemonstrative bravery, the many skills, the untameable beauty, the way he makes love (though they all help!). The unmistakable signal is when Cora takes out her musket during the ambush by the Iroquois – and instead of telling her that ladies don’t do that kind of thing, he hands her his gunpowder pouch.

A scholarly essay must, of course, give examples… and not surprisingly, I didn’t find obvious snacho candidates among most mainstream fiction. But I can name a few in science fiction: Dominic Harlech, aka Niki Falcon in Emma Bull’s Falcon; Radu Drac in Vonda McIntyre’s Aztecs and Superluminal; the Servitors in Sheri Tepper’s The Gate to Women’s Country – who turn out to be the real men, rather than the so-called Warriors. And off the top of my head, I can think of four in film: Trevor Goodchild (Marton Csokas) in the film version of Aeon Flux; Sam Gillen (Jean Claude van Damme, who would have thunk!) in Nowhere to Run; Rob Roy McGregor (Liam Neeson) in Rob Roy; and, of course, Hawkeye (Daniel Day-Lewis) in The Last of the Mohicans. In that film, what pinpoints him as the quintessence of snachismo is not his undemonstrative bravery, the many skills, the untameable beauty, the way he makes love (though they all help!). The unmistakable signal is when Cora takes out her musket during the ambush by the Iroquois – and instead of telling her that ladies don’t do that kind of thing, he hands her his gunpowder pouch.

The God Abandons Antony

The God Abandons Antony