The Heirs of Prometheus

Wednesday, May 28th, 2008Note: Like anyone who’s breathing, I have been tracking the Phoenix Lander. So I thought this might be a good moment to share a personal memory of one of its ancestors. That one did not survive to fulfill its mission, but the dream stayed alive. What I said then is even more true today, almost a decade later. The Greek version of this article was published in the largest Greek daily, Eleftherotypia (Free Press).

It’s slightly cloudy — unusual for sunny Florida. The ocean-scented air is alive with birds: gulls, pelicans, hawks. On a wooden platform, a group of people of all ages and colors is squinting fixedly at a point on the horizon about two kilometers away, where a gantry holds a slim rocket that balances a tiny load on its nose. A level voice announces from the loudspeakers: “The T minus ten holding period is over. We’re going forward.”

The people break into wild cheers, then fall eerily silent. Curious children are shushed and told to look there, there! Final adjustments are made to cameras and binoculars. The minus ten holding period is the last chance to abort. The weather was such that until this moment the decision to launch could change.

Like heartbeats, the announcements come. “T minus five… minus three… minus one… T minus thirty seconds… minus twenty seconds… minus ten seconds…” Now you can hear a pin drop. “Nine… eight.. seven… six… five… four…. three… two…” All the spectators shiver, holding their breath.

“Liftoff!”

A fiery flower unfurls on the horizon. From within it emerges a dark blue arrow that pierces the sky, followed by a cloud of white smoke. The ground shakes from the aftershocks. Seconds later, the sonic boom reaches the group. Many of its members are wiping tears without making any effort to hide them — despite the Anglosaxon tradition that discourages public displays of emotion.

And so, in front of my eyes, accompanied by tears and cheers, loaded with blessings and expectations, on January 3, 1999, the Polar Lander left for Mars. After a year of travel, it will touch down on the South Pole of Mars and search for subterranean water.

Why is this mission important? Today Mars is bone-dry, but its surface features betray that it enjoyed liquid water in the past — gullies, wadis and coasts of now-vanished seas are clearly visible in its photos.

Wherever there’s water, there is life. Martian life, if it exists, is almost certainly at the bacterial stage. But if we find it — or just its petrified remains — this will give us the very first proof that we are not alone, that our Universe, vast as it is, may perhaps contain companions.

Such a discovery will overshadow even the upheavals brought about by Copernicus and Darwin. It will break our eternal isolation and force us to completely revise our ideas of the universe and our place in it. The existence of extraterrestrial life will make us understand that we occupy no special place in the universe, that we are observers or fellow travelers and not, by the grace of any god, lords of creation. And it will force us to remember yet again that humanity is a single entity, traveling on a lone ship that makes it way through an indifferent sea.

For a bearer of such a heavy literal and symbolic load, the Polar Lander is miniscule. The size of a small fridge, jam-packed with instruments, it resembles a beetle, with the fragile solar panels standing in for wings. Among other things, it carries a microphone. For the first time, we will hear the sounds of the winds on another planet.

The inventiveness required to put together a space mission is almost unbelievable. As an example, the two tiny instruments that will detect the potential underground water and send the results to the orbiters must achieve the following: land unscathed after enduring the heat of atmospheric entry; pierce like missiles a thick layer of ice without harming their electronic circuits; enter the ground in the correct orientation without rudders, parachutes, engines or further instructions from Earth; and last but not least, do exact measurements with fragile instruments the size of a small human finger. Such demands are the order of the day for NASA’s technical personnel.

The morning before the launch, the engineers and scientists who achieved these miracles explained to us the goals of the mission and the details of the craft and its instruments. All were trembling with tension and fatigue, but their eyes burned with their vision.

These men and women, whose names will never become known or celebrated like those of the astronauts, already dedicated four years of their lives to this mission — and will give as many in the future, analyzing the information sent by the spacecraft. Like the artisans who built Stonehenge, the Pyramids, Aghia Sofia, the Taj Mahal, these people grow old in obscurity, with their only reward the knowledge that will be added to the annals of the species — and with their sole but immense privilege to be the first who glimpse the New Worlds.

Because, in the end, that is the real mission. Exploration of space is the large collective effort of this era that will change all our lives. Not only because we may discover alien life. Closer to home, this exploration is the guarantee for our continuation.

Earth is truly the Garden of Eden, but its magnanimity has spoiled us. Now, having grown used to the caresses of a planet ideal for our needs as well as the luxuries of advanced technology, we have almost exhausted the finite resources of our paradise. With the pressures of the human population, the rest of the biosphere is contracting daily and the quality of life is dwindling for all except the privileged.

It is true that we have not solved our problems here, and inevitably we will take them with us wherever we go. However, if we wait till the last moment to launch the ships with the seeds of terrestrial life, the likelihood of finding another welcoming harbor before we suck our parent planet dry will dwindle to zero. We must prepare for this great step now, while we still have leeway.

All this is felt by those that came to wave farewell to the Lander. That is why they brought their children to share the stargazing, something very unusual for Americans who almost always separate their social activities by age: they want the next generation to remember that this tiny spacecraft and its companions carry our future.

Sojourner, the Lander’s predecessor, was the first to walk on Mars — a kid’s toy cart, which sent us thousands of pictures of the planet’s surface. A famous cartoonist showed it leaving human footprints, and he was right: these miniscule spacecraft, that have opened windows to the universe for us without costing even a millionth of a military aircraft, are the expression of our best selves. And they, along with our radio and television emissions, are our heralds and ambassadors to the unknown.

The day after the launch, the NASA PR office showed us around. The Space Center is within a national forest full of endangered flora and fauna. If the Federal Government had not inadvertently protected it, that entire coast would be a solid cement wall. The paths cross canals full of water lilies where alligators sun themselves. Egrets and cranes fish in the shallows. Above the rioting semi-tropical greenery rise the scaffoldings of the launch pads and the buildings where the spacecraft are built.

The building where the craft undergo final assembly is so large that it creates thermals. As a result, it is constantly circled by a fleet of hawks — a fitting retinue. Its vast interior creates such local temperature gradients that often it rains or fogs. Like an Escher drawing, it teems with skywalks and protrusions that hold entire labs. Looking down from the top you feel like a feather, as though here gravity doesn’t hold sway.

The launch pad that we visited is called Alpha. From there rose the Apollos for their trips to the moon. The pad is a giant Meccano set, a plaything for Titans. The surrounding wire fences are full of holes, from the jagged fragments of asphalt that erupt from the floor whenever it siphons the flames of liftoff.

I bent and took a piece of the worn, burnt asphalt. These scaffoldings don’t launch just spaceships and falcons. Around them fly the dreams of all humanity. This place is sacred, it has received sacrifices — the crew of the first Apollo, the crew of the Challenger, the nameless technicians of the missions. And the deity to whom these offerings are dedicated is Prometheus, who rose against mightier powers. His rebellion made us who we are and brought us here, in pain and in glory.

Credits: Top, Prometheus Stealing Fire, by André Durand.

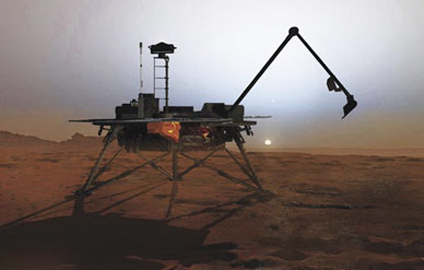

Bottom, the Phoenix Lander on Mars, by Corby Waste.