How well like a man fought the Rani of Jhansi,

How valiantly and well!

— Indian ballad

My opinion of steampunk is low. However, last week’s lovely Google doodle by Jennifer Hom reminded me that I like at least one steampunk work. After I wrote my Star Trek book, I was asked why I did so. My reply was The Double Helix: Why Science Needs Science Fiction. Here is its opening paragraph:

The first book that I clearly remember reading is the unexpurgated version of Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues under the Sea. Had I been superstitious, I would have taken it for an omen, since the book contains just about everything that has shaped my life and personality since then. For me, the major wonder of the book was that Captain Nemo was both a scientist and an adventurer, a swashbuckler in a lab coat, a profile I imagined myself fulfilling one day.

I was five when I first read the novel. Unlike Anglophone readers, I was lucky enough to have the complete version rather than the bowdlerized thin gruel that resulted in Verne being consigned to the category of “children’s author”. Of course, 20,000 Leagues set me up for the inevitable fall. It prompted me to read most of Verne’s other works, in which he’s as guilty of infodumps, cardboard characters and tone-deaf dialogue as most “authors of ideas”. Too, his books are boys’ treehouses: I can recall two women in those I read, both as lively as wooden idols. Even so, Captain Nemo stands apart among Verne’s characters, both in his depth and in the messages he carries.

Verne has Aronnax describe Nemo at length when he first sees him. It takes up more than a page — but even now I remember my frustration when I reached the end and found out Verne says exactly nothing about Nemo’s build, hue, eye and hair color or shape. All he has told, in excruciating detail, is that Nemo looks extraordinarily intelligent and has a formidable presence.

However, my book copy contained several sepia-tinted plates from Disney’s film version of the book (in lieu of Édouard Riou’s engravings that accompanied the original editions). I had no idea who the actors were – I discovered that James Mason was British in my early twenties. On the other hand, several hints in the book, including the “liquid vowel-filled” language spoken by his multinational crew, coded the captain of the Nautilus as different. So in my mind Nemo was olive-skinned, black-haired. He looked like my father the engineer, like my father’s seacaptain father and brothers, like the andártes of the Greek resistance. He looked like me.

However, my book copy contained several sepia-tinted plates from Disney’s film version of the book (in lieu of Édouard Riou’s engravings that accompanied the original editions). I had no idea who the actors were – I discovered that James Mason was British in my early twenties. On the other hand, several hints in the book, including the “liquid vowel-filled” language spoken by his multinational crew, coded the captain of the Nautilus as different. So in my mind Nemo was olive-skinned, black-haired. He looked like my father the engineer, like my father’s seacaptain father and brothers, like the andártes of the Greek resistance. He looked like me.

He acted like the andártes, as well. He sided with the downtrodden, from helping a Ceylonese pearl diver to giving guns to the Cretans risen against the Turks. And when he lost companions, he wept. Yet he was not merely a warrior; he was also a polymath. Besides being a crack engineer, a marine biology expert and an intrepid explorer, he spoke half a dozen languages, kept a huge library, and was a discerning art collector and a talented musician. The Nautilus is the precursor of Star Trek’s Enterprise: a ship of science and culture that can also wage war. Too, Nemo’s conversations bespoke someone from an old civilization tempered by melancholic wisdom – not an insouciant triumphalist.

Then there was the Lucifer strain that appealed to me just as much, coming as I did from a clan of resistance fighters. Nemo embodies the motto by which I have come to live my life: Never complain, never explain. He’s an evolved incarnation of the Byronic hero. His name is not only the Latin version of Outis (Noone) that Odysseus gave to Polyphemus; it is also a cognate of Nemesis (Vengeance). Today’s security agencies would call Nemo a terrorist, even though he fights in self-defense and retribution after invaders massacre his family and occupy his homeland.

Since victors write history, the losers’ freedom fighters become the winners’ murderers. Beyond that, there’s a fundamental difference between Nemo and fanatics like bin Laden: Nemo is not fighting to establish an Ummah, an Empire, a Utopia, not for power, riches, or glory. He’s not a fundamentalist secure in celestial approval of his actions. He is deeply conflicted and feels grief and guilt whenever he exacts revenge.

In this, Nemo shares his creator’s determined Enlightenment outlook. Verne was never apologetic about his heroes’ secularism or love of political freedom. However, Pierre-Julien Hetzel, Verne’s excessively hands-on editor, was acutely mindful of social and political conventions. As a result, Verne has Nemo go through a deathbed act of contrition in the vastly inferior Mysterious Island – something totally at odds with his character in 20,000 Leagues. Left to himself, Verne might have given a far darker ending to the first novel, as Disney did in his film version and as Verne later did with Robur, a coarsened power-obsessed Nemo clone.

Verne had originally conceived Nemo as a Polish scientist fighting against Russian oppressors. Hetzel did not want to alienate the lucrative Russian market. Also, neither Poland nor Russia are known for their naval prowess: a Russian-hating Nemo would put a serious crimp on the sea battle drama in 20,000 Leagues. So when Verne reveals Nemo’s provenance in The Mysterious Island, he makes him an Indian prince, son of the Rajah of Bundelkhand. Lakshmi Bai, the Rani of Jhansi (a region of Bundelkhand), was one of the leaders of the Sepoy Uprising, the same uprising that cost Nemo his family and home. It makes me glad to think Captain Nemo, Prince Dakkar, may have been Lakshmi Bai’s cousin – that they grew up together, friends and like-minded companions. I’m equally glad Nemo is free of the poisonous concepts of caste purity.

Verne had originally conceived Nemo as a Polish scientist fighting against Russian oppressors. Hetzel did not want to alienate the lucrative Russian market. Also, neither Poland nor Russia are known for their naval prowess: a Russian-hating Nemo would put a serious crimp on the sea battle drama in 20,000 Leagues. So when Verne reveals Nemo’s provenance in The Mysterious Island, he makes him an Indian prince, son of the Rajah of Bundelkhand. Lakshmi Bai, the Rani of Jhansi (a region of Bundelkhand), was one of the leaders of the Sepoy Uprising, the same uprising that cost Nemo his family and home. It makes me glad to think Captain Nemo, Prince Dakkar, may have been Lakshmi Bai’s cousin – that they grew up together, friends and like-minded companions. I’m equally glad Nemo is free of the poisonous concepts of caste purity.

Who could animate Captain Nemo’s complexities and dilemmas onscreen? Mason may have been ethnically incorrect, but he truly captured Nemo – both his torment and his charisma. The incarnations since Mason have been anemic and/or off-key. In The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Naseeruddin Shah did his best with the paper-thin material he was given, but the film was so unremittingly awful that I’ve wiped it from long-term memory. Besides him, I have a few other possibles in mind and I’m open to additional suggestions:

Jean Reno, real name Juan Moreno, the stoic ronin whose Andalusian parents had to leave Cadiz during Franco’s regime; Ghassan Massoud, who wiped the floor with the other actors (except Edward Norton as the uncredited Baldwin) as Saladin in Ridley Scott’s Kingdom of Heaven; Ken Watanabe, who left Tom Cruise in the dust in The Last Samurai; Oded Fehr, who made the screen shimmer as the paladin Ardeth Bey in The Mummy; in a decade or so, Ioan Gruffudd, whom Guinevere should have taken as a co-husband in Antoine Fuqua’s Arthur; also in about a decade (provided he keeps lean), Naveen Andrews, the soulful Kip in The English Patient.

It goes without saying that I have an equally long list of candidates who could embody Captain Nemo as a woman – but I’ll keep these names for that never-never time when this becomes possible without the venomous ad feminem criticisms (some from prominent women) that greeted Helen Mirren as Prospero. Because gender essentialism aside, Captain Nemo was not someone I wanted to fall in love with, but someone I wanted to become: a warrior wizard, a creator, a firebringer.

Addendum 1: I received excellent additions to the Nemo candidate list. Calvin Johnson suggested Ben Kingsley, real name Krishna Pandit Bhanji, who needs no further introduction (Calvin and I also agreed that Laurence Fishburne in Morpheus mode would be great for the part). Anil Menon proposed the equally formidable Gabriel Byrne. Eloise Lanouette brought up Alexander (endless full name) Siddig who keeps getting better, like fine wine.

I also received a palpitation-inducing… er, tantalizing thought-experiment from Kay Holt; namely, a film in which each of my candidate Nemos inhabits a parallel reality. Ok, I’ll stop grinning widely now.

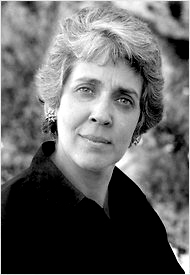

Addendum 2: I got e-mails expressing curiosity about my female Nemo candidates. So here’s the list. Again, I welcome suggestions:

Julia Ormond, who radiates intelligence and made a tough-as-nails underdog hero in Smilla’s Sense of Snow; Karina Lombard, who brought tormented Bertha Mason to vivid life in The Wide Sargasso Sea; Salma Hayek, the firebrand of Frida; Michelle Yeoh, who bested everyone (including Chow Yun Fat) in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon; Angela Bassett, who wore kickass Lornette “Mace” Mason like a second skin in Strange Days; last but decidedly not least, Anjelica Huston — enough said!

Great additional suggestions have come for this half as well: Lena Headey who made a terrific Sarah Connor, Indira Varma of Kama Sutra — both in about ten years’ time. Sotiría Leonárdhou, who set the world on fire in Rembetiko. And, of course, Sigourney Weaver, the one and only Ellen Ripley.

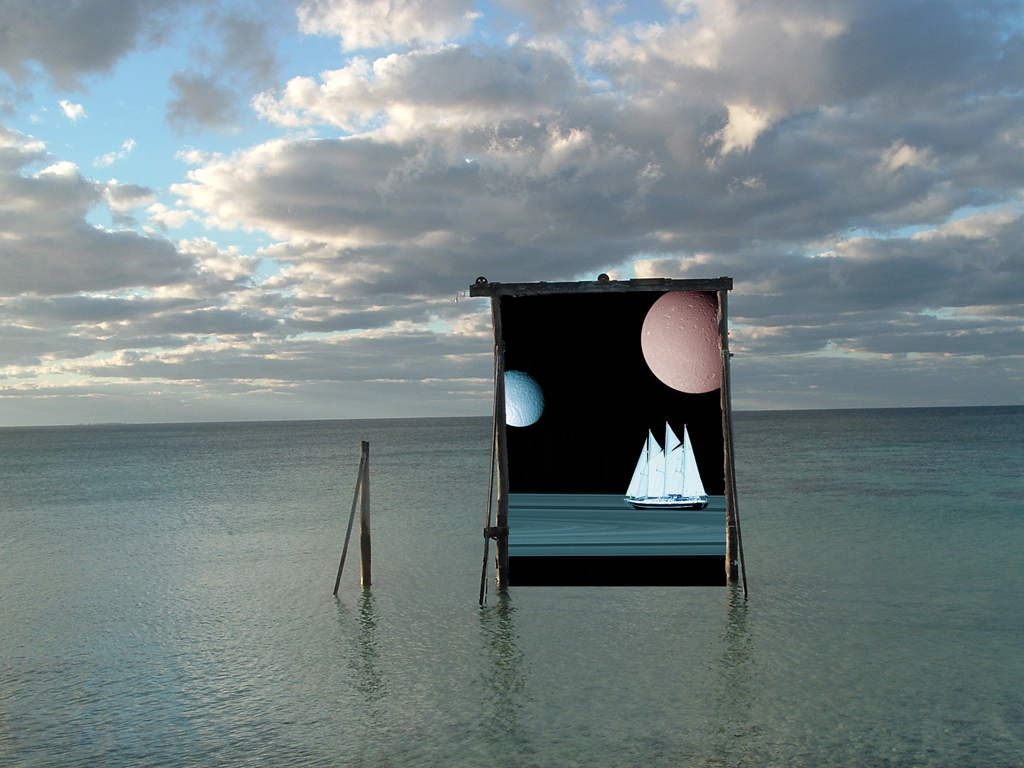

Images: 1st, the Nautilus as envisioned by Tom Scherman; 2nd, Captain Nemo (original illustration by Édouard Riou; detail); 3rd, James Mason as Nemo; 4th and 5th, my Nemo candidates, left to right; 4th, the men — top, Jean Reno (France/Spain), Ghassan Massoud (Syria), Ken Watanabe (Japan); bottom, Oded Fehr (Israel), Ioan Gruffudd (Wales), Naveen Andrews (India/UK); 5th, the women — top, Julia Ormond (UK), Karina Lombard (Lakota/US), Salma Hayek (Mexico); bottom, Michelle Yeoh (Hong Kong), Angela Bassett (US), Anjelica Huston (US).