Making Aliens 2: The Journey

Thursday, March 8th, 2007 The Repercussions of Planetary Settlement

The Repercussions of Planetary Settlement

by Athena Andreadis

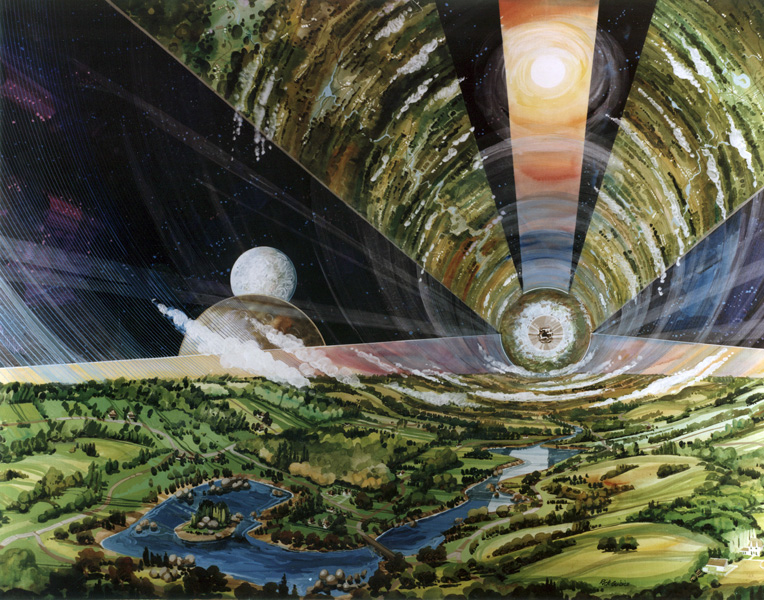

Art image: courtesy of NASA

Part 2: The Journey

The distances between star systems are truly vast. To reach Mars, our nearest neighbor, takes six months with our current propulsion systems. Even fusion drives or light sails will not shorten stellar trips by much. Truly exotic means, such as warp drives and stable wormholes, may never leave the realm of fantasy because of fundmental constraints — the lightspeed limit may prohibit the former, gravitational instability the latter.

So our current alternatives are the so-called “arks” or long-generation ships, which have to be enclosed and self-sustaining. The trouble is, we have never successfully engineered such a system, and the gobs of waste circling all our space vessels (particularly Mir) are sad witnesses to this fact. Biosphere 2, the first experiment to attempt creation of a totally enclosed, self-sufficient environment ended up with oxygen leaks, ecological breakdown, and severe carbon dioxide poisoning — plus virulent infighting among the participants.

Fortunately, Biosphere 2 was set up on Earth, where the surroundings could easily come to the rescue. That will not be the case for a ship halfway to another planet. In this respect, environmentalism with its insistence on recycling and conserving resources is not only a good strategy for our increasingly crowded planet but may also devise partial solutions to the problem of long, slow interplanetary journeys.

A long journey has additional associated dangers beyond ecological breakdown. One is the loss of biodiversity for all the species within the ship, including the human passengers. Another is mass psychosis, which can grip entire nations and will be far more dangerous in an isolated context deprived of outside corrective influences. Either can lead to the loss of technology, which has happened here on Earth as a result of discontinuities from environmental catastrophes, large-scale migrations or disruptive conquests. Classical Greeks and medieval Europeans forgot the sophisticated drainage and sewage systems of the Minoans and Romans, respectively; the Native Americans forgot the wheel; the Tasmanians forgot boats and even fire. The persistent refusal of NASA to study complicated human interactions in space, including sex, has left us ignorant and highly vulnerable in this respect.

If a spaceship loses technology, its passengers may not be able to survive on a hostile planet. Terrestrial examples of isolated settlements illustrate this danger. The medieval Norse settlements on Greenland as well as several European colonies in New England perished from malnutrition despite their high-tech beginnings. The Polynesians of Pitcairn and Easter Islands stripped their lush islands of vegetation (thereby breaking down their ecology, losing all trade and cutting their communication lines). Their solution was to resort to cannibalism, which led to their extinction within a few hundred years of their arrival.

Making Aliens 1: Why Go at All?

Making Aliens 2: The Journey

Making Aliens 4: Playing God I

The Repercussions of Planetary Settlement

The Repercussions of Planetary Settlement  Those who are, like me, left-handed and older than forty probably recall being forced to write with our right hand and the frustration of using many “handed” tools, including scissors, rulers and computer mice. We also remember being told that left handers are prone to depression, immune deficiencies, shorter lives, dyslexia and a host of other woes… and no wonder, given the drizzle of harassment! Finally, there is the conflation of left with evil, wrong or inept in practically all religions and languages (sinister, gauche, linkisch…), not to mention most political systems.

Those who are, like me, left-handed and older than forty probably recall being forced to write with our right hand and the frustration of using many “handed” tools, including scissors, rulers and computer mice. We also remember being told that left handers are prone to depression, immune deficiencies, shorter lives, dyslexia and a host of other woes… and no wonder, given the drizzle of harassment! Finally, there is the conflation of left with evil, wrong or inept in practically all religions and languages (sinister, gauche, linkisch…), not to mention most political systems.