Introductory note: Through Paul Graham Raven of Futurismic, I found out that Charles Stross recently expressed doubts about the Singularity, god-like AIs and mind uploading. Being the incorrigible curious cat (this will kill me yet), I checked out the post. All seemed more or less copacetic, until I hit this statement: “Uploading … is not obviously impossible unless you are a crude mind/body dualist. // Uploading implicitly refutes the doctrine of the existence of an immortal soul.”

Clearly the time has come for me to reprint my mind uploading article, which first appeared at H+ magazine in October 2009. Consider it a recapitulation of basic facts.

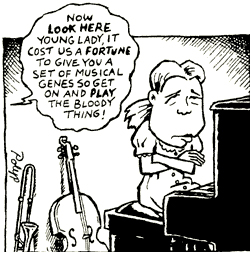

When surveying the goals of transhumanists, I found it striking how heavily they favor conventional engineering. This seems inefficient and inelegant, since such engineering reproduces slowly, clumsily and imperfectly, what biological systems have fine-tuned for eons — from nanobots (enzymes and miRNAs) to virtual reality (lucid dreaming). An exemplar of this mindset was an article about memory chips. In it, the primary researcher made two statements that fall in the “not even wrong” category: “Brain cells are nothing but leaky bags of salt solution,” and “I don’t need a grand theory of the mind to fix what is essentially a signal-processing problem.”

And it came to me in a flash that most transhumanists are uncomfortable with biology and would rather bypass it altogether for two reasons, each exemplified by these sentences. The first is that biological systems are squishy — they exude blood, sweat and tears, which are deemed proper only for women and weaklings. The second is that, unlike silicon systems, biological software is inseparable from hardware. And therein lies the major stumbling block to personal immortality.

The analogy du siècle equates the human brain with a computer — a vast, complex one performing dizzying feats of parallel processing, but still a computer. However, that is incorrect for several crucial reasons, which bear directly upon mind portability. A human is not born as a tabula rasa, but with a brain that’s already wired and functioning as a mind. Furthermore, the brain forms as the embryo develops. It cannot be inserted after the fact, like an engine in a car chassis or software programs in an empty computer box.

Theoretically speaking, how could we manage to live forever while remaining recognizably ourselves to us? One way is to ensure that the brain remains fully functional indefinitely. Another is to move the brain into a new and/or indestructible “container”, whether carbon, silicon, metal or a combination thereof. Not surprisingly, these notions have received extensive play in science fiction, from the messianic angst of The Matrix to Richard Morgan’s Takeshi Kovacs trilogy.

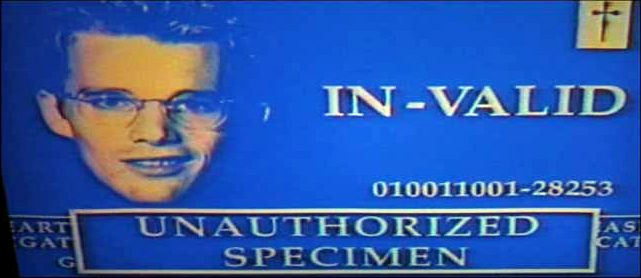

To give you the punch line up front, the first alternative may eventually become feasible but the second one is intrinsically impossible. Recall that a particular mind is an emergent property (an artifact, if you prefer the term) of its specific brain – nothing more, but also nothing less. Unless the transfer of a mind retains the brain, there will be no continuity of consciousness. Regardless of what the post-transfer identity may think, the original mind with its associated brain and body will still die – and be aware of the death process. Furthermore, the newly minted person/ality will start diverging from the original the moment it gains consciousness. This is an excellent way to leave a clone-like descendant, but not to become immortal.

What I just mentioned essentially takes care of all versions of mind uploading, if by uploading we mean recreation of an individual brain by physical transfer rather than a simulation that passes Searle’s Chinese room test. However, even if we ever attain the infinite technical and financial resources required to scan a brain/mind 1) non-destructively and 2) at a resolution that will indeed recreate the original, additional obstacles still loom.

What I just mentioned essentially takes care of all versions of mind uploading, if by uploading we mean recreation of an individual brain by physical transfer rather than a simulation that passes Searle’s Chinese room test. However, even if we ever attain the infinite technical and financial resources required to scan a brain/mind 1) non-destructively and 2) at a resolution that will indeed recreate the original, additional obstacles still loom.

To place a brain into another biological body, à la Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, could arise as the endpoint extension of appropriating blood, sperm, ova, wombs or other organs in a heavily stratified society. Besides being de facto murder of the original occupant, it would also require that the incoming brain be completely intact, as well as able to rewire for all physical and mental functions. After electrochemical activity ceases in the brain, neuronal integrity deteriorates in a matter of seconds. The slightest delay in preserving the tissue seriously skews in vitro research results, which tells you how well this method would work in maintaining details of the original’s personality.

To recreate a brain/mind in silico, whether a cyborg body or a computer frame, is equally problematic. Large portions of the brain process and interpret signals from the body and the environment. Without a body, these functions will flail around and can result in the brain, well, losing its mind. Without corrective “pingbacks” from the environment that are filtered by the body, the brain can easily misjudge to the point of hallucination, as seen in phenomena like phantom limb pain or fibromyalgia.

Additionally, without context we may lose the ability for empathy, as is shown in Bacigalupi’s disturbing story People of Sand and Slag. Empathy is as instrumental to high-order intelligence as it is to survival: without it, we are at best idiot savants, at worst psychotic killers. Of course, someone can argue that the entire universe can be recreated in VR. At that point, we’re in god territory … except that even if some of us manage to live the perfect Second Life, there’s still the danger of someone unplugging the computer or deleting the noomorphs. So there go the Star Trek transporters, there go the Battlestar Galactica Cylon resurrection tanks.

Let’s now discuss the possible: in situ replacement. Many people argue that replacing brain cells is not a threat to identity because we change cells rapidly and routinely during our lives — and that in fact this is imperative if we’re to remain capable of learning throughout our lifespan.

It’s true that our somatic cells recycle, each type on a slightly different timetable, but there are two prominent exceptions. The germ cells are one, which is why both genders – not just women – are progressively likelier to have children with congenital problems as they age. Our neurons are another. We’re born with as many of these as we’re ever going to have and we lose them steadily during our life. There is a tiny bit of novel neurogenesis in the olfactory system and possibly in the hippocampus, but the rest of our 100 billion microprocessors neither multiply nor divide. What changes are the neuronal processes (axons and dendrites) and their contacts with each other and with other cells (synapses).

These tiny processes make and unmake us as individuals. We are capable of learning as long as we live, though with decreasing ease and speed, because our axons and synapses are plastic as long as the neurons that generate them last. But although many functions of the brain are diffuse, they are organized in localized clusters (which can differ from person to person, sometimes radically). Removal of a large portion of a brain structure results in irreversible deficits unless it happens in very early infancy. We know this from watching people go through transient or permanent personality and ability changes after head trauma, stroke, extensive brain surgery or during the agonizing process of various neurodegenerative diseases, dementia in particular.

However, intrepid immortaleers need not give up. There’s real hope in the horizon for renewing a brain and other body parts: embryonic stem cells (ESCs, which I discussed recently). Depending on the stage of isolation, ESCs are truly totipotent – something, incidentally, not true of adult stem cells that can only differentiate into a small set of related cell types. If neuronal precursors can be introduced to the right spot and coaxed to survive, differentiate and form synapses, we will gain the ability to extend the lifespan of a brain and its mind.

However, intrepid immortaleers need not give up. There’s real hope in the horizon for renewing a brain and other body parts: embryonic stem cells (ESCs, which I discussed recently). Depending on the stage of isolation, ESCs are truly totipotent – something, incidentally, not true of adult stem cells that can only differentiate into a small set of related cell types. If neuronal precursors can be introduced to the right spot and coaxed to survive, differentiate and form synapses, we will gain the ability to extend the lifespan of a brain and its mind.

It will take an enormous amount of fine-tuning to induce ESCs to do the right thing. Each step that I casually listed in the previous sentence (localized introduction, persistence, differentiation, synaptogenesis) is still barely achievable in the lab with isolated cell cultures, let alone the brain of a living human. Primary neurons live about three weeks in the dish, even though they are fed better than most children in developing countries – and if cultured as precursors, they never attain full differentiation. The ordeals of Christopher Reeve and Stephen Hawking illustrate how hard it is to solve even “simple” problems of either grey or white brain matter.

The technical hurdles will eventually be solved. A larger obstacle is that each round of ESC replacement will have to be very slow and small-scale, to fulfill the requirement of continuous consciousness and guarantee the recreation of pre-existing neuronal and synaptic networks. As a result, renewal of large brain swaths will require such a lengthy lifespan that the replacements may never catch up. Not surprisingly, the efforts in this direction have begun with such neurodegenerative diseases as Parkinson’s, whose causes are not only well defined but also highly localized: the dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra.

Renewing the hippocampus or cortex of a Alzheimer’s sufferer is several orders of magnitude more complicated – and in stark contrast to the “black box” assumption of the memory chip researcher, we will need to know exactly what and where to repair. To go through the literally mind-altering feats shown in Whedon’s Dollhouse would be the brain equivalent of insect metamorphosis: it would take a very long time – and the person undergoing the procedure would resemble Terry Schiavo at best, if not the interior of a pupating larva.

Dollhouse got one fact right: if such rewiring is too extensive or too fast, the person will have no memory of their prior life, desirable or otherwise. But as is typical in Hollywood science (an oxymoron, but we’ll let it stand), it got a more crucial fact wrong: such a person is unlikely to function like a fully aware human or even a physically well-coordinated one for a significant length of time – because her brain pathways will need to be validated by physical and mental feedback before they stabilize. Many people never recover full physical or mental capacity after prolonged periods of anesthesia. Having brain replacement would rank way higher in the trauma scale.

The most common ecological, social and ethical argument against individual quasi-eternal life is that the resulting overcrowding will mean certain and unpleasant death by other means unless we are able to access extra-terrestrial resources. Also, those who visualize infinite lifespan invariably think of it in connection with themselves and those whom they like – choosing to ignore that others will also be around forever, from genocidal maniacs to cult followers, to say nothing of annoying in-laws or predatory bosses. At the same time, long lifespan will almost certainly be a requirement for long-term crewed space expeditions, although such longevity will have to be augmented by sophisticated molecular repair of somatic and germ mutations caused by cosmic radiation. So if we want eternal life, we had better first have the Elysian fields and chariots of the gods that go with it.

Images: Echo (Eliza Dushku) gets a new personality inserted in Dollhouse; any port in a storm — Spock (Leonard Nimoy) transfers his essential self to McCoy (DeForest Kelley) for safekeeping in The Wrath of Khan; the resurrected Zoe Graystone (Alessandra Torresani) gets an instant memory upgrade in Caprica; Jake Sully (Sam Worthington) checks out his conveniently empty Na’vi receptacle in Avatar.

I get out of my car,

I get out of my car,