The Blackbird Singing: Sapfó of Lésvos

Friday, March 27th, 2015Come my holy lyre, become my voice, sing!

— Sapfó, Fragment 118

Introduction: I read, write and celebrate poetry. As I said in a previous entry, I grew up in a culture where poetry was not precious and hermetic, but a vital way of expression that belonged to all. Poems were set to music and sung, poets were bards that could fuel revolutions.

The article below first appeared in Stone Telling issue 2 (Dec. 2010). It had a slightly longer title and contained a few lines of Hellenic text that WordPress won’t reproduce. I’ve rendered Hellenic (Greek) words as they are pronounced by native speakers to convey as accurate an aural impression as possible. Thus, Sapfó, not Sappho – and the p is voiced; Lésvos, not Lesbos; Afrodhíti, not Aphrodite, where dh=th as in “the” and i=ee as in “tree”. The very imperfect translations are mine.

———-

When I was four, I taught myself to read – I had to suss out the activity that drew my adored, adoring father’s attention away from me. My parents, bowing to the inevitable, gave me access to their entire library. About four years later, I was poring over the essays of poet and firebrand journalist Kóstas Várnalis. In one of them, he ridiculed the vapidity and reactionism of contemporary popular love songs, in which the woman was always a mute, passive object of obsession. As a salutary contrast, he juxtaposed these “immortal words from a divine voice”:

When I was four, I taught myself to read – I had to suss out the activity that drew my adored, adoring father’s attention away from me. My parents, bowing to the inevitable, gave me access to their entire library. About four years later, I was poring over the essays of poet and firebrand journalist Kóstas Várnalis. In one of them, he ridiculed the vapidity and reactionism of contemporary popular love songs, in which the woman was always a mute, passive object of obsession. As a salutary contrast, he juxtaposed these “immortal words from a divine voice”:

The Moon has set and the Pleiades,

midnight, time passes,

and I lie alone.

The language was an archaic dialect from two and a half millennia ago and I was too young to have sexual needs, so the subtext sailed right over my head. But the naked yearning pierced my solar plexus. And that was my first encounter with the Blackbird of Lésvos, the Tenth Muse, Sapfó.

Sapfó (in Aeolian dialect, Psápfa) was born around 620 BC in Lésvos, one of the three large Aegean islands that hug the coast of Asia Minor. From an aristocratic family, she lived her life there except for a stint of political exile in Sicily – a common fate for Hellenes, who have politics in their blood. Sapfó’s contemporaries unanimously (and, oddly for Mediterranean men, ungrudgingly) hailed her as the greatest lyric poet in the Hellenic-speaking world. Level-headed Sólon, the Athenian lawgiver, is said to have declared upon hearing one of her songs, “I just want to learn it, then die.”

Of Sapfó’s nine collections, a single poem has come down to us intact and her music is totally lost, although she’s credited with inventing the Mixolydian mode (today’s Locrian, used in both classical and jazz music). Some of her lines survived as quotes in literary textbooks of Greek or Roman writers. The rest are literally fragments – one potsherd and papyrus shreds from mummy wrappings or, most abundantly, from the rubbish heaps of Oxírynhos (“Sharpsnouted”), a Hellenistic city in Upper Egypt. Yet the shards of her poems, often not even whole sentences, have cast a long shadow over poetry.

The few, uncertain facts of Sapfó’s life come mostly from her own poetry, although her exile is mentioned on the Parian Marble, a chronological stela that haphazardly covers a millennium of history. Hellenic, Roman and Byzantine sources also give stray biographical facts but their accuracy is questionable.

Here are the tenuous gleanings from these sources: Sapfó’s father, possibly called Skamandhrónimos, died when she was a child. She had three brothers and felt protective of the youngest. She had an adored daughter whom she named after her mother Kleís, “Glory of Deeds” (Fragment 132 reads, I have a beautiful child whose face is like golden flowers, my beloved Kleís, whom I would not exchange for all of Lydia…). Her husband was said to be a rich sea-merchant, Kerkílas of Ándhros, but this is widely considered a pun since it can be translated as “Prick from the isle of Man” – though Ándhros is real enough: the Cycladic island closest to the mainland, it has a formidable maritime tradition.

A far likelier lover for Sapfó was her friend and rival Alkaíos, a fellow aristocrat and poet to whose political party she belonged. His faction ended up the loser during the power struggle between the older families and the upstarts headed by Pittakós (Pittakós prevailed, ruled well, and is remembered as one of the Seven Sages of ancient Hellás, the originator of the Golden Rule). After returning from the Sicilian exile precipitated by her political actions, Sapfó founded a thíassos (band) of well-born young women whose social and literary prominence bred rival imitators. Subsequent generations have variously interpreted it as a finishing school, a cult of lay priestesses, an artists’ salon, a separatist lesbian enclave – or a circle of friends who were also colleagues in poetry and whose bonds included the physical, a configuration akin to similar groups of aristocratic and/or creative men of many cultures and eras, from Macedonian hetéroi to Shogunate courtiers.

A far likelier lover for Sapfó was her friend and rival Alkaíos, a fellow aristocrat and poet to whose political party she belonged. His faction ended up the loser during the power struggle between the older families and the upstarts headed by Pittakós (Pittakós prevailed, ruled well, and is remembered as one of the Seven Sages of ancient Hellás, the originator of the Golden Rule). After returning from the Sicilian exile precipitated by her political actions, Sapfó founded a thíassos (band) of well-born young women whose social and literary prominence bred rival imitators. Subsequent generations have variously interpreted it as a finishing school, a cult of lay priestesses, an artists’ salon, a separatist lesbian enclave – or a circle of friends who were also colleagues in poetry and whose bonds included the physical, a configuration akin to similar groups of aristocratic and/or creative men of many cultures and eras, from Macedonian hetéroi to Shogunate courtiers.

Sapfó was said to be small and dark. Even her admirer Alkáios called her violet-tressed – but in Hellenic folk and literary tradition the blackbird is the equal of the nightingale. Finally, dating from the Hellenistic era there’s a tradition that Sapfó fell into a postmenopausal frenzy of unrequited love for Fáon, a much younger boatman. She reputedly trailed him slavishly and finally flung herself off the cliffs of Lefkás, an island in the Ionian sea. However, Fáon means “Shining” and he’s linked to Afrodhíti (“Foamrisen”) in her destructive aspect: he’s a version of Adonis. That, coupled with the fact that Sapfó considered Afrodhíti her patron god and wrote poems lamenting the wavering of inspiration with age, puts a rather different complexion on the story.

Whether Sapfó was lésvian by inclination as well as by birth has been a thorny thicket of assumptions and taboos. The time gap, the paucity of information and the physical and linguistic inaccessibility of her poetry have resulted in Sapfó being different things to different people, depending on her audience’s individual and collective context. But the issue is also hard to untangle because Sapfó lived in a time and place that not only differed radically from that of her explicators but was also unique within Hellenic culture of the early classical era.

Unlike the starkness of most of Hellás, Lésvos is green and rich. Lésvians were considered passionate, sensual and fond of beauty. Social strata were shallow and fluid in a merchant maritime culture where rulers ate the same austere food as farmers and all citizens were active in politics. Aristocrats of both genders seem to have been casually bisexual and polyamorous, though they took care to maintain inheritances and lines. Unlike Athenians, they allowed their women education and did not confine them to the house; unlike Spartans, they did not subjugate them to state purposes. Female activities extended beyond “Kinder, Küche und Kirche” and the fact that they were exiled implies at least indirect participation in civic affairs. These liberties were disapprovingly ascribed to the influence of the nearby Lydians and Carians. If classical Hellás is equated with medieval France, Lésvos was its Languedoc, which bred powerful queens, courts of love – and troubadours.

And so we come to the crux: Sapfó’s ability as a maker (which is the literal meaning of “poet” in Hellenic). Her poetry is as easily recognizable as Minoan frescoes. There are several extrinsic reasons for this. She is one of the very few poets who wrote in Aeolian, an older relative of Dorian whose relationship to Ionian-derived Athenian is that of a soft Southern accent to Californian. Aeolian dropped initial aitches, frequently changed “e” and “i” to “a” and “t” to “p” and pushed word stress to earlier syllables. Moon in Ionian is Selíni, in Aeolian it’s Sélana. Whereas Ionian is a fast-flowing river, Aeolian is long, deep seaswells.

And so we come to the crux: Sapfó’s ability as a maker (which is the literal meaning of “poet” in Hellenic). Her poetry is as easily recognizable as Minoan frescoes. There are several extrinsic reasons for this. She is one of the very few poets who wrote in Aeolian, an older relative of Dorian whose relationship to Ionian-derived Athenian is that of a soft Southern accent to Californian. Aeolian dropped initial aitches, frequently changed “e” and “i” to “a” and “t” to “p” and pushed word stress to earlier syllables. Moon in Ionian is Selíni, in Aeolian it’s Sélana. Whereas Ionian is a fast-flowing river, Aeolian is long, deep seaswells.

Sapfó also used a unique meter in much of her poetry, the Sapphic stanza. This consists of three eleven-syllable lines plus a fourth line of five additional syllables known as the Adonic line, a fitting term for a devotee of Afrodhíti. This meter was also used by Alkaíos, Catullus, Horace and such more recent luminaries as Swinburne and Ginsberg.

Sapfó wrote several types of poems, many for public performance: epics, epithalamia, hymns, odes, elegies, dirges. Despite the common assumption that all her poetry is personal, she did not avoid large canvases: two of her larger fragments describe back stories in the Iliad. Besides, to argue that all the poems are “personal” devalues her craft. In any case, Hellenes did not put firewalls between the personal and the political: they were always aware they represented their family, clan and city-state. Many of Sapfó’s poems are first-person and address the listener directly, which gives them a startling immediacy. Sometimes this is is a god – usually Afrodhíti, who is treated as a confidante and ally. More often it’s a beloved friend or a lover. Some of these are men; most are women.

It is safe to say that Sapfó invented the language of desire for the Western world. There is nothing coy or demure about her declarations, they’re as frank and fierce as those of a torch singer. Yet even when impassioned, her words are precise, concrete and minutely calibrated. The phrases and images she was the first to use are now so embedded in the vocabulary of love that she has become the submerged bedrock from which such poems and songs spring. When singers moan I’m on fire, You make me weak in the knees, I hunger for your touch, it’s Sapfó they’re echoing:

Love shook my mind like the wind bends the mountain oaks.

I simply want to die now that she left me.

You came – it’s good you did, I sickened for you.

You cooled my thoughts that burned with longing.

And of course there’s that cry of anguish, Fragment 31:

As a god he seems to me – that man across from you,

who attends you when you whisper to him and laugh softly.

But me – my heart tears in my breast, and as soon as I see you

I lose my voice and my words fade. My tongue is crushed

and a slow fire goes through my body, my eyes darken,

my ears ring, I sweat, tremble and turn paler than grass.

I’m near death but must dare everything, poor as I am.

Poetry is essentially untranslatable. Sapfó’s even more so, given its fragmentation, dialect, meter and boldness. Fellow poets down the centuries tried to shoehorn her work into acceptable content and style norms for their era while acknowledging her incandescence. The task eluded even Hellenes. The first good translation into contemporary Hellenic was by Sotíris Kakísis in 1979; it became the basis of a song cycle. And I keep hoping for someone with the chops of Olga Broumas to do it for English.

Poetry is essentially untranslatable. Sapfó’s even more so, given its fragmentation, dialect, meter and boldness. Fellow poets down the centuries tried to shoehorn her work into acceptable content and style norms for their era while acknowledging her incandescence. The task eluded even Hellenes. The first good translation into contemporary Hellenic was by Sotíris Kakísis in 1979; it became the basis of a song cycle. And I keep hoping for someone with the chops of Olga Broumas to do it for English.

More surprising is the dearth of novels based on Sapfó, considering what rich material she would make. Only five 20th century Anglophone novels have her as their focus. None of them captures her or her era and all have dated badly (although one of them, The Other Sappho by Ellen Frye, at least rings authentic in its settings and song snatches because Frye spent time in Hellás translating its folksongs).

In Hellenic culture, women were thought to be less disciplined than men in their erotic desire. Pragmatic and prone to compartmentalizing, Hellenes feared passionate love as an emotion that could breach boundaries, bring disorder and upheaval. They counted it among the god-inflicted illnesses (rage, ecstasy, panic) that could drive humans mad, make them forget customs and obligations. So Sapfó stands out not only because of her gender, the gender of most of her love objects and her directness (each amazing on its own). She also stands out because she unapologetically embraced this divine madness – and single-handedly raised it to an art as honed and prominent as the vaunted epic.

When Hellenes said The Poet and used a masculine suffix, they meant Homer; when they used a feminine suffix, they meant Sapfó. Sapfó is quicksilver, saffron and wild silk; seabreeze and crackling flame. To hear her, even in pieces, is to drink starlight, glimpse the elusive blackbird that ushers the dawn.

Further reading/listening

Anne Carson, If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho

Marguirite Johnson, Sappho

Margaret Reynolds, The Sappho Companion

Sotíris Kakísis, Sapfó, the Poems

Aléka Kanellídhou sings Sapfó; music by Spíros Vlassópoulos, translation by Sotíris Kakísis

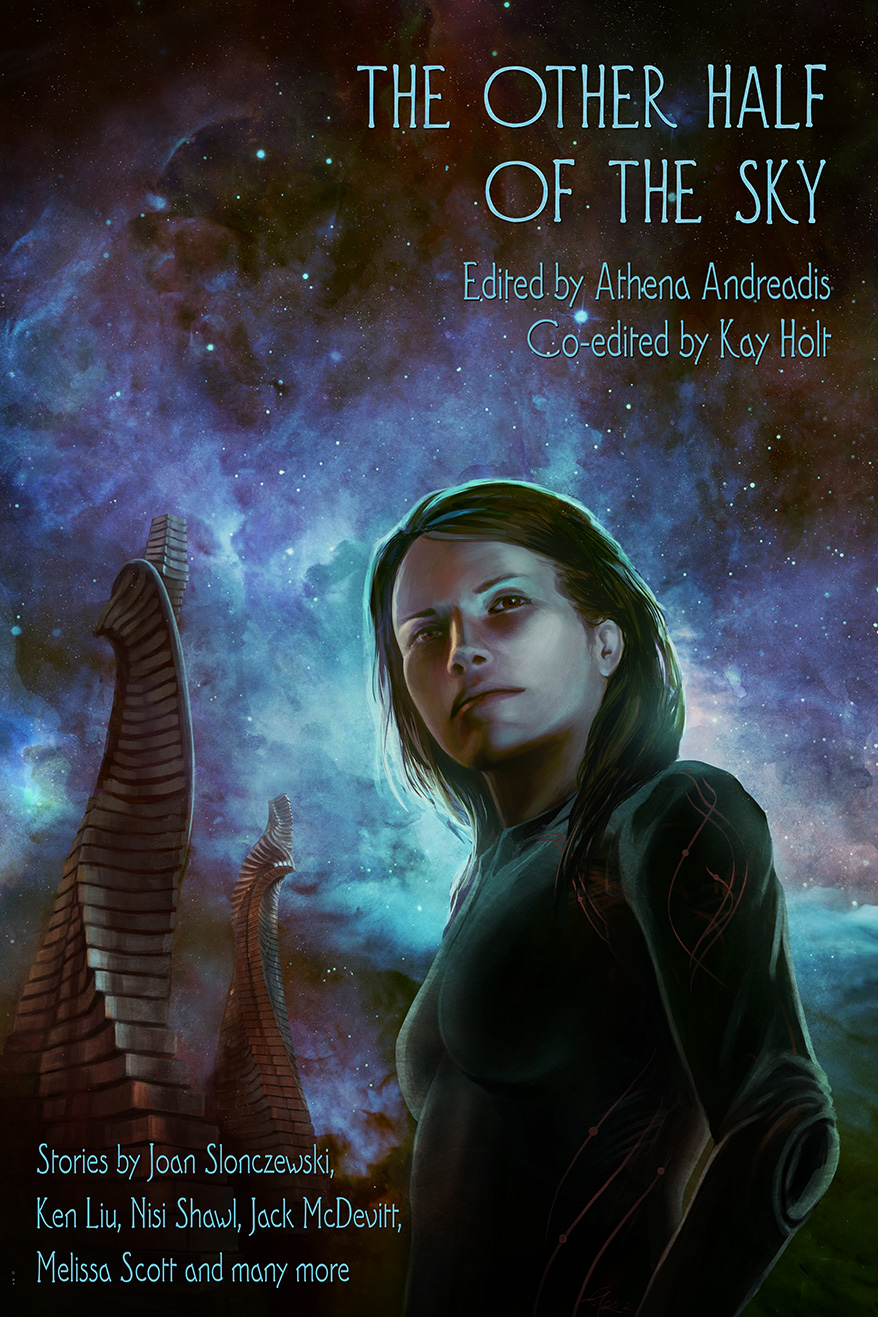

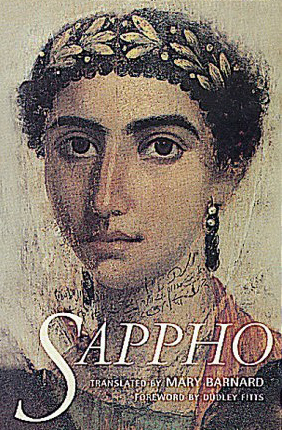

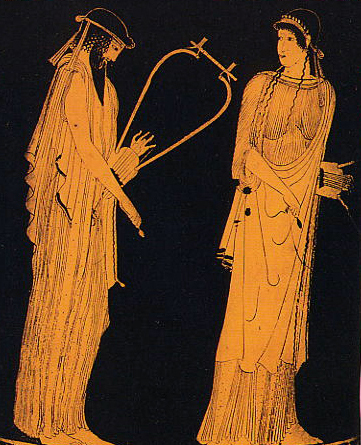

Images: 1st, The cover of Mary Barnard’s Sapfó translation (a Fayum portrait); 2nd, Sapfó and Alkaíos; Red-figured vessel from Akragas, Sicily, 470 BC; 3rd, the papyrus that bears Sapfó’s Fragment 98; 4th, Sapfó, Roman copy of a Hellenistic work

Imagine you’ve landed on an earth-like planet. You can live there without erecting domes, but there’s a gas dissolved in the atmosphere that makes you slightly ill. You rarely feel fully yourself. You have some difficulty gathering your thoughts, you have to take time to parse your every action. You spend excessive amounts of effort trying to get basics done.

Imagine you’ve landed on an earth-like planet. You can live there without erecting domes, but there’s a gas dissolved in the atmosphere that makes you slightly ill. You rarely feel fully yourself. You have some difficulty gathering your thoughts, you have to take time to parse your every action. You spend excessive amounts of effort trying to get basics done.

Athena’s notes: An exploration of immortality that starts similar to Yanagihara’s but goes in a totally different direction is Le Guin’s

Athena’s notes: An exploration of immortality that starts similar to Yanagihara’s but goes in a totally different direction is Le Guin’s