“…they see women as radiant and merciless as the dawn…” — Semíra Ouranákis, captain of starship Reckless at planetfall (Planetfall).

“…they see women as radiant and merciless as the dawn…” — Semíra Ouranákis, captain of starship Reckless at planetfall (Planetfall).

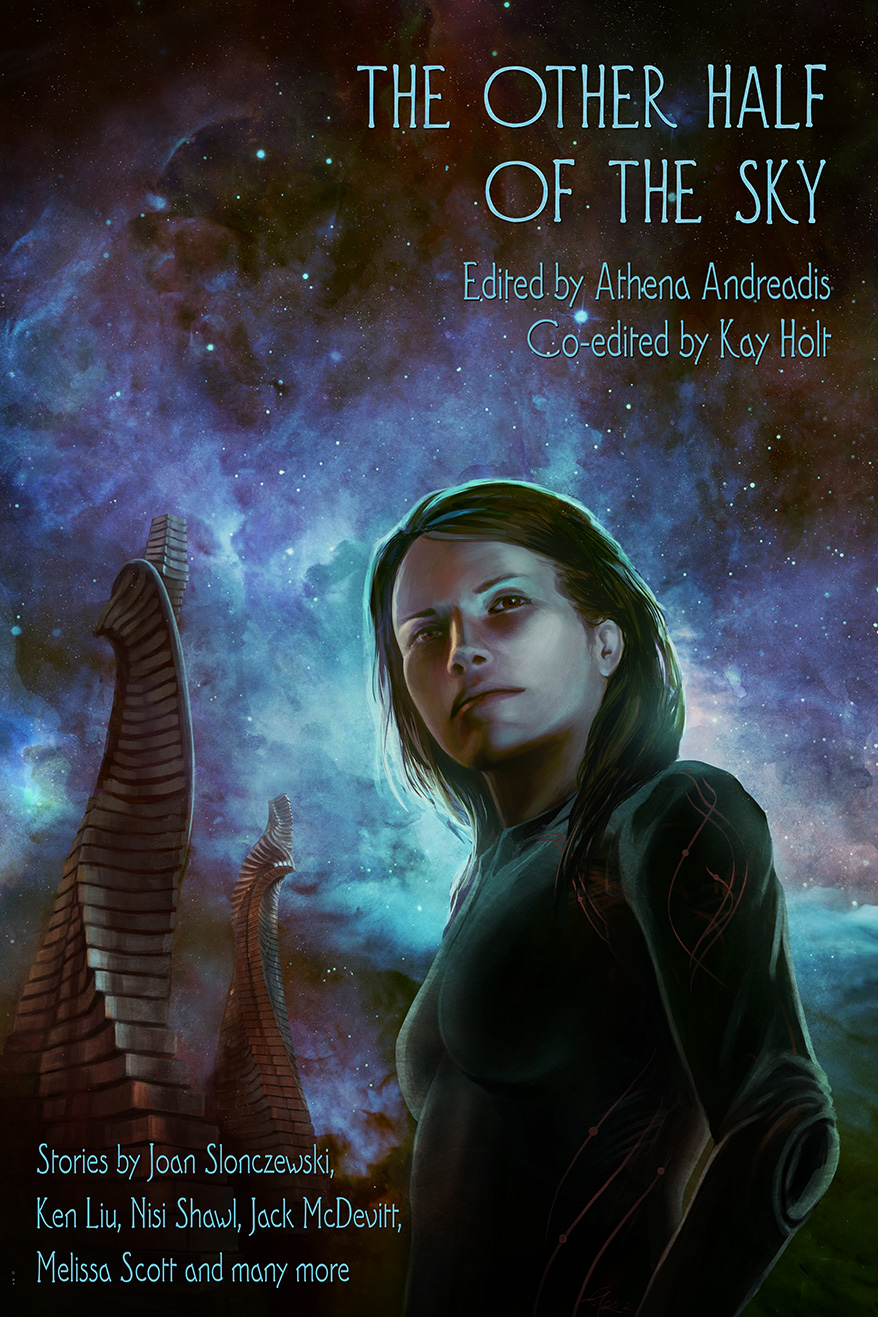

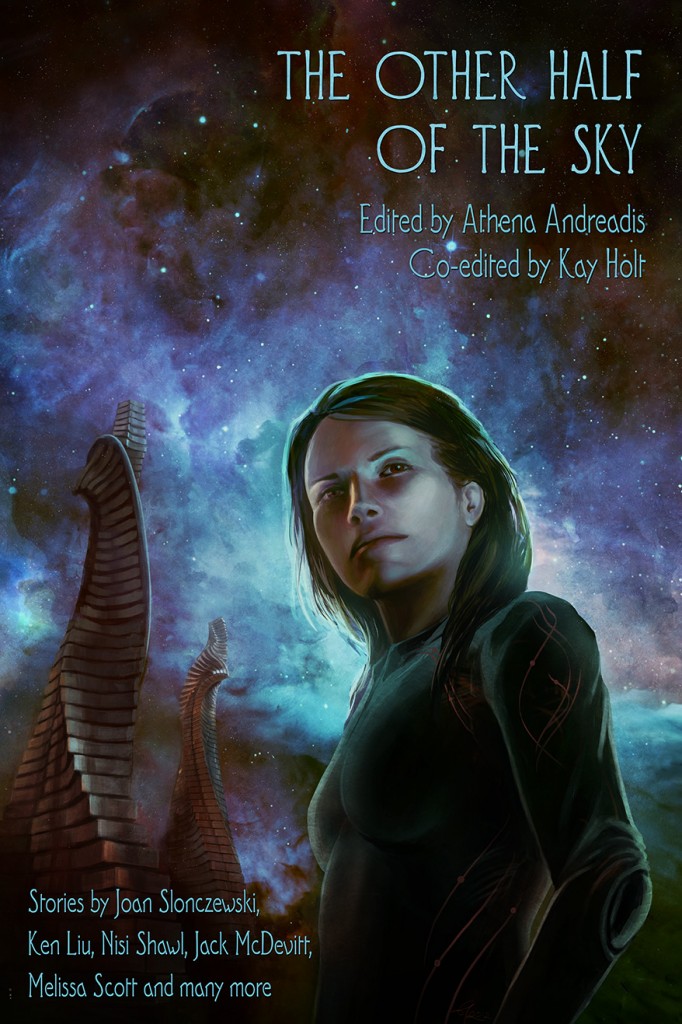

I decided to whet appetites. Below is not only the TOC of the anthology, but also the opening bars of each movement that’s part of this symphony. At the end of this post is a widget designed with great care and flair by Kate Sullivan, our publisher, that displays the excerpts as a beautiful mini-book.

I won’t say more, the snippets speak for themselves. [ETA: so does the cover, which eloquently embodies the anthology’s contents.]

The Other Half of the Sky

Athena Andreadis, Introduction: Dreaming the Dark

Melissa Scott, Finders

Alexander Jablokov, Bad Day on Boscobel

Nisi Shawl, In Colors Everywhere

Sue Lange, Mission of Greed

Vandana Singh, Sailing the Antarsa

Joan Slonczewski, Landfall

Terry Boren, This Alakie and the Death of Dima

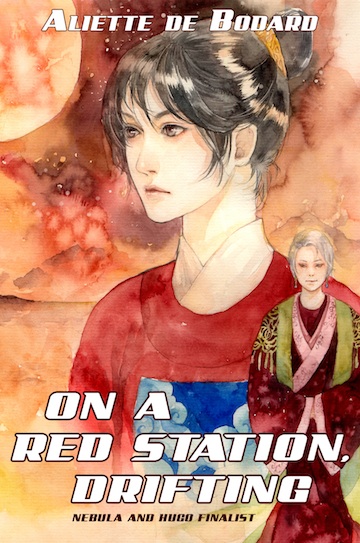

Aliette de Bodard, The Waiting Stars

Ken Liu, The Shape of Thought

Alex Dally MacFarlane, Under Falna’s Mask

Martha Wells, Mimesis

Kelly Jennings, Velocity’s Ghost

C. W. Johnson, Exit, Interrupted

Cat Rambo, Dagger and Mask

Christine Lucas, Ouroboros

Jack McDevitt, Cathedral

Let the storytelling begin:

Melissa Scott, Finders

A thousand years ago the cities fell, fire and debris blasting out the Burntover Plain. Most of the field was played out now, the handful of towns that had sprung up along the less damaged southern edge grown into three thriving and even elegant cities, dependent on trade for their technology now rather than salvage. Cassilde Sam had been born on the eastern fringe of the easternmost city, in Glasstown below the Empty Bridge, and even after two decades of hunting better salvage in the skies beyond this and a dozen other worlds, the Burntover still drew her.

Alexander Jablokov, Bad Day on Boscobel

Dunya stopped just outside Phineus’s unit to calm herself down. Otherwise she would burst in and start screaming at him. That was no way to start a check-in meeting with one of her refugees.

That gave her a chance to realize that she looked like hell. She’d already had one fight that morning, with her daughter Bodil, and afterwards she had rushed out, unsnapped and unbrushed. It was hard enough to manage someone like Phineus, all Martian and precise, without giving him more ammunition about how lax things were here, among the asteroids.

Nisi Shawl, In Colors Everywhere

Trill walked home through the Rainshadow Mountains with Adia, her former mentor. Not alone.

The sky had been high all day. Now, with evening, it came low, wetting them and their surroundings with mist. Silver beaded the fuzz beneath their feet.

Adia was tough, though an elder. She walked steadily, without complaint. She ought to have been tired even before they started; she and Trill had spent the week teaching a cohort of tens-to-thirteens how to weave buildings.

Sue Lange, Mission of Greed

In the third week after gagarin123 landed on an unnamed planet sweeping through a solar system claimed by ValeroCorp, First Mechanic Bertie Lai’s chance for fame slowly swirled down the shitter.

And just yesterday things had been moving along swimmingly. René Genie, the mission biologist, had not yet found sentient life; the geologist, Aadil Alzeshi, had discovered beautiful 1.4. Specifically, he’d hit some pitchblende with enough uranium in it for ValeroCorp to recoup the cost of this mission.

Vandana Singh, Sailing the Antarsa

There are breezes, like the ocean breeze, which can set your pulse racing, dear kin, and your spirit seems to fly ahead of you as your little boat rides each swell. But this breeze! This breeze wafts through you and me, through planets and suns, like we are nothing. How to catch it, know it, befriend it? This sea, the Antarsa, is like no other sea. It washes the whole universe, as far as we can tell, and the ordinary matter such as we are made of is transparent to it. So how is it that I can ride the Antarsa current, as I am doing now, steering my little spacecraft so far from Dhara and its moon?

Joan Slonczewski, Landfall

Most college sophomores spent their summer running toyworlds while catching sun at air-conditioned disappearing beaches. Jenny Ramos Kennedy spent hers at the Havana Institute for Revolutionary Botany, which students called the Botánica. At the Botánica, Jenny worked with ultraphytes, Earth’s cyanide-emitting extraterrestrial invaders. Could she discover how to engineer ultraphyte chromosomes–to control them genetically, before they poisoned the planet?

Terry Boren, This Alakie and the Death of Dima

When Dine Paloan asked this woman, Alakie, to leave before destruction arrived, she refused at first. She had trained to be Paloan’s pilot, but this Alakie had never thought she would be leaving without Dine. So instead of accepting the Dinela’s wishes, this Alakie helped to send Paloan’s other tokens back to Cassin, and she stayed.

Aliette de Bodard, The Waiting Stars

The derelict ship ward was in an isolated section of Outsider space, one of the numerous spots left blank on interstellar maps, no more or no less tantalising than its neighbouring quadrants. To most people, it would be just that: a boring part of a long journey to be avoided–skipped over by Mind-ships as they cut through deep space, passed around at low speeds by Outsider ships while their passengers slept in their hibernation cradles.

Ken Liu, The Shape of Thought

Cat’s Cradle turns into Painted Handkerchief turns into Dish of Noodles turns into Manger turns into Fishing Net. These are but the first of the Two Hundred Variations developed by bored human children on the Long Journey.

I was once one of them.

Young Ket hums as zie holds up zir hands, the string wound tight around the fingers. Zie glances at me and I wave back. Zie has the same long graceful neck and bulbous body as zir parent, Tunloji. Watching zem is like watching a younger version of my lover.

Alex Dally MacFarlane, Under Falna’s Mask

Mar-teri broke her confinement to burn alsar for her dead sisters. Under thin moonlight she stepped out of the unmarried adults’ caravan for the first time in two months–stones crunching under her feet, chives brushing against her bare ankles–carrying the bunch of alsar she was supposed to burn in her caravan. As if honouring them from afar could be enough.

The opening lines of Falna’s song slipped into Mar-teri’s head. Such a fierce song, when the woman wearing Falna’s mask channelled generations of anger–how Mar-teri had longed to wear that mask!

Martha Wells, Mimesis

Jade spotted Sand as he circled down from the forest canopy, a grasseater clutched in his talons. She said, “Finally.” It would be nice to eat before dark, so they could clear the offal away from the camp without attracting the night scavengers.

It was Balm who said, “I don’t see Fair.”

Jade frowned, scanning the canopy again. They were standing in the deep grass of the platform they had chosen to camp on, and it was late afternoon in the suspended forest and getting difficult to hunt by sight.

Kelly Jennings, Velocity’s Ghost

I hate planets. Filthy, heavy, smelly, and this one was leaking.

“It’s rain,” Rida said. “It’s not a leak, it’s part of their exchange.”

“It’s snow.” Tai lurked just up corridor, close enough that I could hear him both hard and via the uplink. “Rain is the wet one.”

“This is wet,” Rida objected.

“Can we focus?” I demanded. “Rida?”

Braced on the rim of the rock pool by the bistro hatch, Rida flashed me a capture of his desk screen, with the vid of our target unshifted. “She’s still talking, boss.”

C. W. Johnson, Exit, Interrupted

The Door wasn’t so much heavy as reluctant to move, as if they were carrying it, one at each end, through molasses. “Why is it like this?” Saiyul asked as she leaned into the resistant thing.

Ashil shrugged the best he could with his hands full. “How should I know?”

A bead of perspiration slid down Saiyul’s face, right into the scar on her cheek. It had healed, mostly, but it itched where her oxygen mask rubbed against it.

Cat Rambo, Dagger and Mask

If you had asked Eduw if he loved Grania, he would have been indignant. Naturally he did. He loved all his targets.

Not at first, of course. He was put off. That scar that marred her face, it hurt to look at. It wasn’t an uncommon condition, despite what the meddies said. Some people rejected plas-flesh. It didn’t take, didn’t renew lost skin, didn’t rebuild damaged features. For some it even seemed to make things worse.

Christine Lucas, Ouroboros

The dead philosopher came out of his cavern only when both the moons of Mars were below the horizon. Or so the legend claimed.

Under a clear sky over the Martian wilderness, Kallie focused her hearing and sought the faintest sound that might confirm his existence. Nothing. The nanobots lining her auditory nerves redoubled their efforts. Still nothing. Yet. She turned her attention towards the base at northeast, under the shadow of Olympus Mons. No alarms, no sirens, no one on her trail. They hadn’t noticed her absence. Yet. But they would, and they’d unleash the Enforcer.

Jack McDevitt, Cathedral

Matt Sunderland gazed at the Earth, which was just edging out from behind the Moon. From the L2 platform, Luna, of course, dominated the sky, a vast gray globe half in sunlight, half in shadow, six times larger than it would have appeared from his Long Island home. Usually, it completely blocked the gauzy blue and white Earth. On the bulkhead to his left, the Mars or Bust flag still hung, its corners fastened by magnets.

Mars or Bust.

Image: Girl under the Milky Way, by Babak A. Tafreshi

Through the recent spike in the volume of tweets, I became aware of two things: 1) there is a Hugo award category called “Best Fan Writer” and 2) according to the rules, I’ve been eligible for it since 2008. At least in principle, because the real universe is significantly different.

Through the recent spike in the volume of tweets, I became aware of two things: 1) there is a Hugo award category called “Best Fan Writer” and 2) according to the rules, I’ve been eligible for it since 2008. At least in principle, because the real universe is significantly different. To increase my already wild popularity, I penned two bookend articles that gore sacred oxen. A contribution to a Mind Meld at SF Signal about

To increase my already wild popularity, I penned two bookend articles that gore sacred oxen. A contribution to a Mind Meld at SF Signal about

I was elated to watch LotR consistently exceed my (initially not very high) expectations. But after The Hobbit, I feel dread at the thought that Jackson may decide to embark on The Silmarillion next. Perhaps he should read the folktale of the fisherman’s wife. Or read what Marx said about repeating history: the first time, it’s tragedy; the second time, farce.

I was elated to watch LotR consistently exceed my (initially not very high) expectations. But after The Hobbit, I feel dread at the thought that Jackson may decide to embark on The Silmarillion next. Perhaps he should read the folktale of the fisherman’s wife. Or read what Marx said about repeating history: the first time, it’s tragedy; the second time, farce.