Close Your Eyes and Think of Apóllon

Sunday, June 24th, 2012The Oracle of Dhelfoí, known by her title of Pythía, was the closest equivalent to a shaman in classical Hellenic culture. In the official version, she delivered her prophecies by entering into a trance and becoming possessed by Apóllon – or by the displaced original owner of that temple and its myth: Python, the serpent/dragon that signified The Great Goddess.

In reality, the prophecies were almost certainly formulated after information had been gleaned from informants and spies (which explains the fabled ambiguity that earned Apóllon the moniker Loxías, Slanted). As for the trance, some archaeologists have linked it to the hallucinogenic effects of ethylene gas, which could have been released into air and water from the hydrocarbon reservoir beneath the limestone strata whenever the bedrock around the temple shifted or cracked. Many argue that the Pythíai were just mouthpieces for Apóllon’s “interpreter” priests. However, the fact that they were post-menopausal women from families of good standing (which, outside Athens, usually implied a modicum of education) suggests that they were more than mere passive vessels. They may have exerted real political influence behind the veils of incense, mystical blather and suffocating male authority. Either way the temple was a hive of political intrigue, as can be garnered from the surviving lists of who consulted it and what replies they received.

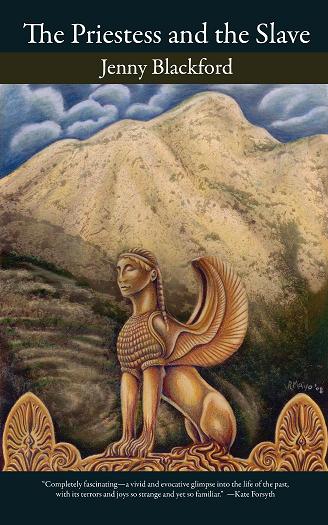

Given the influence of Dhelfoí and the centrality of the oracles to its function, it’s surprising that there have been so few stories about the temple’s doings. I can only recall two: Jenny Blackford’s novel The Priestess and the Slave (Hadley Rille, 2009) and Barry King’s novella Pythia (Colored Lens, Spring 2012). Both have problems that nag at me, but they’re not the disasters that often result when Anglo writers attempt to recreate another culture from the inside – especially classical Hellenic culture, which is invariably treated as public domain.

The two works share more than just their focus; they:

– eschew heroic/famous protagonists in favor of ordinary people;

– are first-person narrations by women who are decidedly non-kickass;

– take place in the same time period, just before the Persian wars (The Priestess and the Slave consists of two stories told in alternating chapters that never intertwine or converge; one of them centers on a Pythía, so I will discuss just this strand vis-à-vis King’s novella);

– incorporate extensive research and wear this effort on their chitons;

– use the occasional Hellenic word to increase verisimilitude;

– teeter on preciousness and melodrama but also contain passages of vivid prose;

– contain a fair amount of cliché situations and cookie-cutter dialogue;

– have many secondary characters that are two-dimensional stereotypes.

The first two choices are unusual, especially in combination: most writers delving in that era chose aristocratic men as protagonists, because they were free to roam physically and intellectually, able to initiate and/or witness pivotal events. The few exceptions (Bagoas in Mary Renault’s The Persian Boy, Xeones in Steven Pressfield’s Gates of Fire, Sappho in Peter Green’s The Laughter of Aphrodite) are either commoner men or noble women. Only Lykaina in Ellen Frye’s The Other Sappho is a common woman (though a gifted one), like Blackford’s and King’s protagonists.

This combination made me read both works very closely. My verdict is that Blackford treats her protagonist and starting material better than King does his, despite his stylistic bravura. As Pythíai, the narrators must deal with fake prophecies connected to Spartan ambitions: King Kleomenes in The Priestess, a soldier called Trivviastes (more about names anon) in Pythia. Both priestesses find themselves involved in events that could change the fate of many, and here is where the authors’ approaches diverge. In simplified terms, The Priestess is adult Apollonian history whereas Pythia is adolescent Dionysian fantasy. Fittingly, the totem of The Priestess is a wolf, that of Pythia, a lion(ess) – animals linked to different aspects of Apóllon, though the latter is more closely associated with his sister Ártemis, The Mistress of Animals.

This combination made me read both works very closely. My verdict is that Blackford treats her protagonist and starting material better than King does his, despite his stylistic bravura. As Pythíai, the narrators must deal with fake prophecies connected to Spartan ambitions: King Kleomenes in The Priestess, a soldier called Trivviastes (more about names anon) in Pythia. Both priestesses find themselves involved in events that could change the fate of many, and here is where the authors’ approaches diverge. In simplified terms, The Priestess is adult Apollonian history whereas Pythia is adolescent Dionysian fantasy. Fittingly, the totem of The Priestess is a wolf, that of Pythia, a lion(ess) – animals linked to different aspects of Apóllon, though the latter is more closely associated with his sister Ártemis, The Mistress of Animals.

Thrasylla, the narrator of The Priestess, exhibits stoic endurance and the clear-eyed, slightly weary worldview of a woman in her fifties. She had an arranged marriage to a decent, average smallholder and mourned a stillborn daughter and subsequent barrenness. She believes in the gods, but calmly, matter-of-factly. There’s no rapture in the duties she discharges soberly and scrupulously. Iola, the narrator of Pythia, is young, a virgin who starts having ecstatic, orgasmic visions after a brick falls on her head in the storeroom where she’s hiding while a Spartan soldier is raping her mother. Whereas Thrasylla tries to guide a fellow priestess who is seduced by riches (the Pythíai were a rotating triad during the temple’s heyday), Iola abandons herself to the god inside her head who manifests as was customary with his type: a playmate who morphs between human and animal, lover and ravisher.

The Priestess retains an even temper and tempo throughout; there are no jolts in it and its ending is open. It is also a relatively linear narrative, with minor flashbacks when Thrasylla thinks back on her younger years (especially her encounter with a rabid wolf, which highlights the combination of uncanniness and pragmatism that makes her an effective Oracle). Thankfully – for me, at least – Thrasylla is a rounded character who does not need to embark on a quest nor has “unfinished business”, the near-obligatory gimmicks that drive too much genre fiction. She is a fully grown human firmly embedded in her context. Despite the gender hobbling of that time and place, her privileged position gives her some power; she is aware of the consequences of wielding it but does not sidestep the associated responsibility.

Pythia reads like an angsty teenager’s diary; it’s full of jolts and indulges in time jumps to such an extent that they make the story’s sidelines hard to track (although plot is not a primary concern – it’s a Cinderella tale with Apóllon as fairy godfather). Iola is a survivor of traumatic events that broke her both physically and mentally, though they also gave her the visions that secured her the position of an atypically young Pythía. Given this premise, it is inevitable that she’s fixated on reconstituting herself and her family and avenging the wrongs done to them. However, the responsibilities of power frighten her, so she decides to “trust the Force.” Lo and behold, when she abandons all agency not only does the villain get his comeuppance but her mother and adoptive father miraculously reappear – married to each other, yet, and owners of a solid homestead where Iola can remain happily ever after.

The Apollonian/Dionysian distinction carries into the stories’ styles. The Priestess adheres to plainness that sometimes shades into grittiness. This decision means that The Priestess lacks the “echoes” that make a story haunt its reader. One example is Thrasylla’s temptation to investigate the Python legend, which is left to lie fallow. Another is the total absence – even in rumor – of Ghorghó, daughter of King Kleoménis, wife of King Leonídhas (of Thermopylai fame), and a formidable political presence in her own right. The sole flourish is the wolf leitmotif, which surfaces whenever there are glimpses of the madness of power. Pythia, besides Iola’s visions (which contain beautiful, if overheated passages) has two symbol-laden recurring images: the serpent, morphing from regenerating lizard to chthonic dragon, the older manifestation of the god that once was a goddess; and the cracked pot, which brings to mind the endless rows of fragmented, imperfectly reconstituted ceramics in museums.

At the same time, it is clear that Blackford has been to Hellás whereas the physical background of King’s story, painstaking research notwithstanding, is the generic “Mediterranean” that also mars such otherwise interesting efforts as Rachel Swirsky’s retelling of Ifighénia’s tale, A Memory of Wind. This difference carries into two other domains: the historic underpinnings of the stories and the names of the characters. Blackford makes the historical references plain in her characters’ dialogue, whereas King omits names and otherwise obscures events to such an extent that even someone steeped in Hellenic history cannot follow without an effort. This may be an attempt to reinforce the mythic atmosphere of the story, but it ends up as a distracting affectation. The names Blackford gives her characters ring mostly true, though she strikes a few false notes; King’s name choices are less fortunate. Spazakia (Iola’s nickname, which is supposed to mean Broken) is plural neuter – plus it is contemporary Hellenic, not classical. The villain is given the subtle name Trivviastes… which means Thrice-Rapist, not a name that even a hard-bitten Spartan parent would endorse.

The result is that Blackford’s novel sustains suspension of disbelief despite its workman prose and even when her characters’ actions are so contrived as to reek of soap opera (such as a seasoned Pythía literally pouting over her colleagues’ jewelry). In contrast, King’s novella, despite its layers and beautiful passages, punctures illusion because of the disempowered protagonist who embodies a gendered cliché, the too many coincidences, the forced obscurity and – for me, specifically – the names. I appreciate what each author tried to achieve; I also appreciate the effort they obviously put into researching the background of their stories. Yet both works could have been far more resonant with a demanding editor and a few more discussions with natives of the culture they chose to depict. If anyone wants to see the theme of a wounded young woman beset by visions treated well, I recommend Evghenía Fakínou’s Astradhení, which I discussed in The Unknown Archmage of Magic Realism.

Images: Aeghéas consulting the Pythía, red-figure kylix, ~450 BCE; Jenny Blackford’s The Priestess and the Slave — its cover depicts another notoriously ambiguous Oracle; Candice Raquel Lee’s Pythia, what the Oracle might have been like pre-Apóllon.