by Calvin Johnson (and a coda by Athena)

Previously: the books.

Translating a well-loved book into a movie is a tricky business. Translating a series of books into a series of movies is even harder.

Peter Jackson did it brilliantly for The Lord of the Rings, through a combination of breathtaking New Zealand landscapes, well-crafted digital special effects, and above all, allowing his actors to act.

Other series were not so lucky. The movie versions of both Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events (drawn from three out of thirteen books) and Phillip Pullman’s The Golden Compass were badly received, especially at the box office, making sequels unlikely. And the Narnia movies are struggling despite a ready-made fan base.

The Harry Potter films, on the other hand, have been a phenomenal success. Last week I wrote about the book series; now, with the release of the penultimate movie, I’ll delve into Harry’s cinematic career.

How and why a movie succeeds or fails is a mystery. Often it’s a matter of a poor match to the strength of cinema, telling a story in images. The Lemony Snicket books were too metafictional to translate well to the big screen. The Narnia books, while bedecked with fantasy flourishes, are primarily about small, personal moral quandries, not a topic that leads to blockbuster multi-repeat viewings (I prefer the BBC Narnia series, with cheesy special effects but a tighter focus on the stories).

Rowling’s books, in contrast, were made for cinema, a criticism in fact leveled at her writing. Although she has her philosophy – that categorizing people by the circumstances of blood and birth is the root of evil – and although Harry has his internal debates, the conflicts in the novels are primarily visual: dramatic revelations, spectacular duels between wizards.

The first two movies were respectful to the point of being stiff. This is unsurprising, as they were directed by Chris Columbus, a protege of Steven Spielberg who learned Spielberg’s maudlin tendencies but none of his visual genius. The series got a real boost in the middle two movies, especially Alfonso Cuarón’s lyrical Prisoner of Azkaban. Leaping up from the best book in the series, Cuarón’s visual inventiveness matched the eccentricities of the Potterverse. Mike Newell managed to keep the spark alive for the magical tournament in The Goblet of Fire.

Alas, the flame guttered low in the remainder of the movies, directed by David Yates. Both The Order of the Phoenix and The Half-Blood Prince were grim, bloated, and not infrequently tedious books, and while Yates hacked out some of the extraneous material, what remained were grim, rushed, and above all obligatory summaries of the books. The Deathly Hallows is famously being broken into two films so it feels less rushed, but viewing Part I felt less like joy and more like an assignment.

Any story, be it book or movie, can be thought of as a tent, much like the wedding tent magically raised early on in The Deathly Hallows: Part I; the structure hangs supported from two or three poles. The problem with The Deathly Hallows is that there are far too many tentpoles and the movie must visit most of them. The flight of the Harry Potters. Dumbledore’s will. Bill and Fleur’s wedding. The escape and fight in the heart of London. Harry’s inherited house. Harry’s birthplace. Luna Lovegood’s home. The House of Malfoy. In between we camp in the wilderness. The book felt lost at this point, as if Rowling knew where she wanted to go but had no idea how to get there, and the feeling is reproduced all too accurately in the movie.

Any story, be it book or movie, can be thought of as a tent, much like the wedding tent magically raised early on in The Deathly Hallows: Part I; the structure hangs supported from two or three poles. The problem with The Deathly Hallows is that there are far too many tentpoles and the movie must visit most of them. The flight of the Harry Potters. Dumbledore’s will. Bill and Fleur’s wedding. The escape and fight in the heart of London. Harry’s inherited house. Harry’s birthplace. Luna Lovegood’s home. The House of Malfoy. In between we camp in the wilderness. The book felt lost at this point, as if Rowling knew where she wanted to go but had no idea how to get there, and the feeling is reproduced all too accurately in the movie.

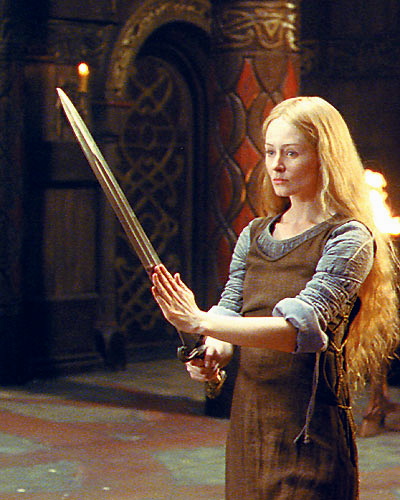

Indeed, although Yates is deft and visually more nimble than Columbus, the movie follows the book a little too faithfully. Part of the challenge of making a movie from a well-loved book is to both keep the uninitiated on board and to make those who have loved the book to tatters see it anew. Peter Jackson succeeded in The Lord of the Rings, allowing us to feel the burdens that Aragorn and Gandalf carry, helping us to see the tides of war rise and ebb in the chaos of the Battle of the Pelennor Fields.

Unfortunately, having to cover so much Yates can add little insight. The most moving scenes are the very beginning and the very end of Part I, as our no-longer-so-young protagonists suffer painful losses in their war against Voldemort.

So why have the Harry Potter movies succeeded? Again, there can be no simple answer, but the producers did have an advantage. For all her flaws, Rowling always understood the series to be Harry’s story, and she resisted having a plethora of viewpoint characters.

The trend in doorstopper fantasy and science fiction novels to have a large number of viewpoint characters is one I have come to loathe, because it makes it harder to emotionally engage with any of the characters. Peter Jackson (last time, I promise) succeeded with The Lord of the Rings because the first movie focused on Frodo’s journey.

By contrast, A Series of Unfortunate Events was more obsessed with Jim Carrey’s Count Olaf and his big eyebrows, and less with the hapless Baudelaire orphans. The Golden Compass would seem to have all the right elements for success: big name stars, dazzling visuals. But one of the joys of the novel is the rebellious, tart-tongued heroine Lyra; onscreen she got lost among the special effects, leaving a leaden, rudderless movie.

Harry Potter was different. J. K. Rowling, the screenwriter Steve Kloves, and the producers and the directors have none of them forgotten that the books and movies are all titled Harry Potter and the Something Something. With tiny exceptions, every frame of the movies is about Harry, and we see the other characters primarily through his eyes. So although the narratives have far too many plot tentpoles, there is one and only one character tentpole. Thus in retrospect having a pedestrian director for the first two movies may have been a wise move. Without this focus I don’t think the audience for the books or the movies would have been nearly as engaged.

Books and movies can both be magical, transcendent experiences that take us into new worlds, showing us new windows even on subjects we think we know intimately. If the Harry Potter films have not quite risen to that level, their popularity show a hunger for magic in our lives. And somewhere out there someone is writing or filming the next magical experience–not perfect, but a story that puts a wire to our hearts, a spark to our imaginations.

Athena’s coda: I haven’t read the Potter books, but I’ve seen all the films except for The Order of the Phoenix and The Half-Blood Prince. I greatly enjoyed the occasional inventive visual: the Lewis chess set brought to life-sized life in The Philosopher’s Stone; the hippogriff making itself comfortable, housecat-like, in The Prisoner of Azkaban; the final exit of the two guest schools’ conveyances in The Goblet of Fire. And I found some of the characters interesting: Snape, McGonagall, Lupin, Black (Dumbledore, not so much – enough lovably irascible father figures already).

Athena’s coda: I haven’t read the Potter books, but I’ve seen all the films except for The Order of the Phoenix and The Half-Blood Prince. I greatly enjoyed the occasional inventive visual: the Lewis chess set brought to life-sized life in The Philosopher’s Stone; the hippogriff making itself comfortable, housecat-like, in The Prisoner of Azkaban; the final exit of the two guest schools’ conveyances in The Goblet of Fire. And I found some of the characters interesting: Snape, McGonagall, Lupin, Black (Dumbledore, not so much – enough lovably irascible father figures already).

However, my overall sense is of fatigued déjà vu, of bloated, plodding spectacles. The borrowings from the Arthurian cycle, the Brontë sisters, Tolkien, Lewis, Le Guin’s Earthsea and the X-Men are obvious — and like a stew with clashing and stale ingredients, they leave me with a sour mind.

Having a single character peg may cover many sins but it uncovers others – especially because Harry’s character is tapioca-bland in the films. For one, it accentuates the fact that despite the sermons about loving everyone regardless of their “race”, this is a hierarchical universe where magic ability is genetically inherited, automatically creating castes (just like the infamous Star Wars midichlorians). Hell, Hagrid practically tugs his forelock. Even within the ranks of magic wielders, some lives are worth more than others: by the end, Harry has a long tally of sacrificed pawns, rooks, knights, bishops, queens… Even Neo’s body count was less in The Matrix trilogy.

For another, a Messianic avenger needs a worthy antagonist and, as Calvin mentioned in Part 1, Voldemort is a moldy caricature — not even a Sauron, let alone a Lucifer. Come to think of it, he looks like Gollum’s brother. Just as you wonder why the hordes of Janissary Pretorians… er, Jedi, cannot handle two Sith in Star Wars, so you wonder why the formidable lineup of white-hat wizards in the Potterverse cannot overcome that whiny slitherer.

Just as crucially, a hero needs a partner of equal stature. In the films, at least, it’s blindingly obvious that Harry’s true soulmate is Hermione (highlighted by the total lack of chemistry between the Hermione/Ron and Harry/Ginny dyads), just as in the X-Men films Wolverine’s true partner is Rogue. I can see Ron getting a consolation prize – but what does Hermione get, who is as good as Harry yet not the Chosen One because of the incorrect location of her body bulges and wrong family pedigree? I predict at least one divorce in the future Potterverse, when she gets tired of washing everyone’s socks. But that is another country.

Finally, the magic in Harry Potter is arbitrary, slaved to the plot twists. This makes it as interesting and attractive as an engine that keeps sputtering out at random moments. People hungering for magic deserve better than regurgitated, least-common-denominator myths.

Finally, the magic in Harry Potter is arbitrary, slaved to the plot twists. This makes it as interesting and attractive as an engine that keeps sputtering out at random moments. People hungering for magic deserve better than regurgitated, least-common-denominator myths.

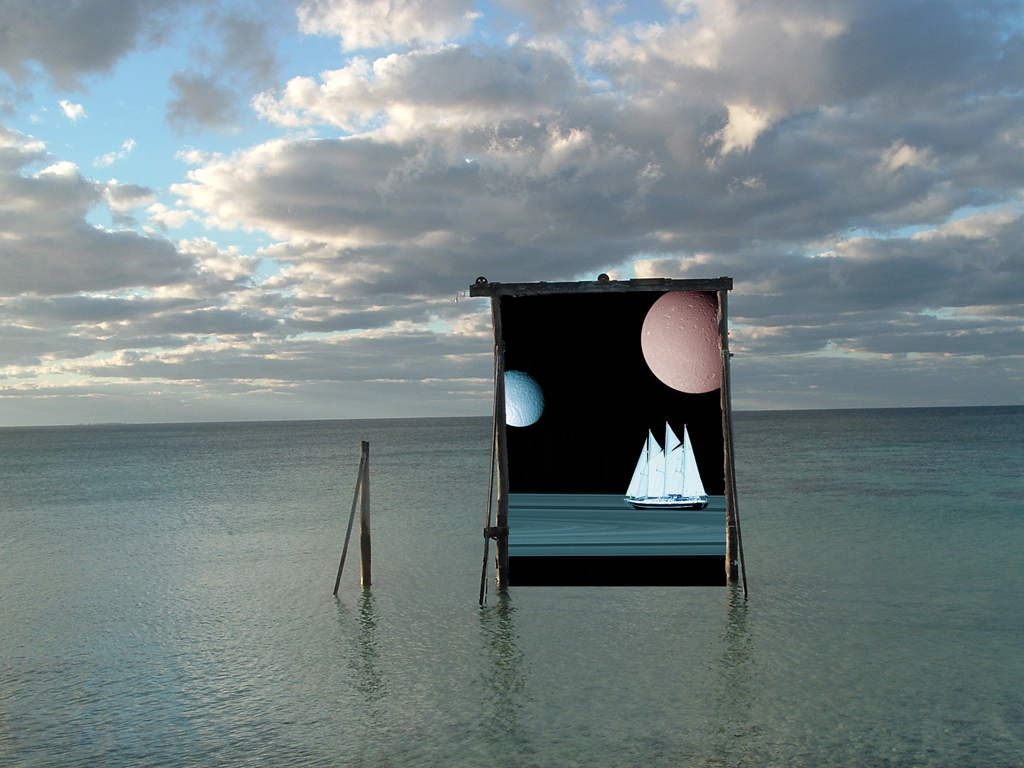

Images: 1st, Aragorn (Viggo Mortensen) and Gandalf (Ian McKellen) in that unexpected triumph, Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings; 2nd, Severus Snape (Alan Rickman) trying to protect his charges from more plodding Potter films; 3rd, pieces from the Lewis chess set (walrus ivory, 12th century); 4th, a far more effective guise for Ralph Fiennes to play an evil or ambiguous antagonist (here shown as Heathcliff in an adaptation of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights).

Bull Spec magazine is a massive labor of love and care by editor Sam Montgomery-Blinn. Issue 6 (Fall 2011) has just come out and in it is a poem of mine, Spacetime Geodesics. Another one, Night Patrol, will appear in issue 7.

Bull Spec magazine is a massive labor of love and care by editor Sam Montgomery-Blinn. Issue 6 (Fall 2011) has just come out and in it is a poem of mine, Spacetime Geodesics. Another one, Night Patrol, will appear in issue 7.