Prologue: After each bout of grant writing, there is a burst of cleaning. And so it came to pass that while neatening my computer I bumped into this article, which I wrote in 1988. What gave me a start was that essentially nothing has changed since then! The essay, edited for the blog, contains seeds that grew into trees – most prominently my Strange Horizons article, We Must Love One Another or Die (not to mention the Snachismo essay or the still-unpublished stories).

The Asymptotic Approach

Critics vaulted over each other trying to name all the sources that Lucas plundered in Willow. Trite, predictable, uneven, derivative, was the collective conclusion. So why am I discussing this film? Because buried underneath the rubble lurks a protofeminist fable – as much as that is possible in a Hollywood film.

It has been one of my greatest, lasting disappointments that in his Star Wars trilogy, with unlimited possibilities for recasting an ancient myth, Lucas chose the most pedestrian solutions (despite the glittering special effects). The films had a single, half-hearted, heroine: An untrained Jedi, ignorant of her powers and dependent on that old female cliché, intuition. At a loss what to do with the excess males, Lucas opted for the tame approach of making one her brother, another her father. Anything wrong with polyandry, in a galaxy so far away?

The worst offense, of course, was that all the wizard/teacher figures were men, too. It makes you wonder: who raised these children and taught them to be human, before training them for galactic knighthood? Willow is a stripped, down-to-earth version of Star Wars, and as such intrinsically inferior. But it does answer some of the questions left unanswered in the trilogy.

Despite its glaring weaknesses, Willow has one overwhelming attraction for me: it takes place in a matriarchy. The king (I am using male nouns on purpose here), Bavmorda, is a woman; the prince, Sorsha, is a woman; the wizard, Fin Raziel, is a woman; and the heir to the throne, around whom the entire action rages, is a girl, Elora. There is a conspicuous absence of fathers, brothers, husbands, sons, a reversal of the customary demographic in stories and films. Women interact, form and break alliances. Too, there is a subtle but discernible resemblance among Raziel, Sorsha and Elora – feisty, angular dark-eyed redheads, not the usual cute, helpless curvaceous blondes.

Well, you say, but the female king is evil, a stereotype. Perhaps, but she is powerful; she vanquishes an entire army without any help from either her ineffectual priests or her blustering but formidable general, whom she slaps around routinely. The benign sorceress is equally powerful and, even more amazingly, she is old! A beautiful, austere woman whose wrinkles add to her character and who, incidentally, is shown practically naked without losing a shred of dignity. Sorsha is a great warrior, the commander of her mother’s armies. If she defies her mother, it is to side with another woman’s cause – and she undergoes the internal growth and maturation cycle usually reserved only for the young men in quest tales.

What about the men – the title character, Willow, and the rogue warrior, Madmartigan? Willow is an androgynous character, with particular emphasis laid on his compassion and sense of community. He is shown more than once changing the future ruler’s diapers. Madmartigan wins Sorsha only by proving his loyalty, with much attendant danger to life and limb and after abandoning the cynical loner stance. More to the point, his children will not automatically inherit the ruler’s seat; it goes to the chosen heir of the women kings.

In short, Willow contains the three telltale signs of a society where women hold real power. In decreasing order of importance, descent is matrilinear, division of labor is diffuse and the men tend to be show-off peacocks. If women are the rulers and teachers, work and roles associated with the gender are respected and desirable. And if women are the brains, men have to cultivate looks, wit and prowess. How else are they going to be noticed by the ruler and chosen for royal stud? At the climax of the film, while the men are hacking at each other down at the courtyard, doing gruntwork, the women are up at the tower, hurling thunderbolts around. By the time the warriors enter the turret, the battle has been waged and won by women’s magic.

I am not arguing that Willow is anywhere near perfection, although I enjoyed it. I am merely suggesting that, things in Hollywood and in our culture being as they are, this may be the closest approximation to woman-friendly mythology that we will get on mainstream film. I strongly recommend that women filmmakers explore the sf/fantasy genre and create the Star Wars equivalent. The formative influence of such films on young people weaned on visual spectacles and bereft of real myths cannot be overestimated.

Photo: Lioness in front of Sunset, 2001, by Thomas R. Wilke

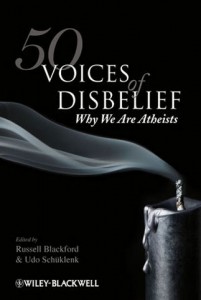

50 Voices of Disbelief (editors Russell Blackford and Udo Schüklenk, publishers Wiley-Blackwell) just went on sale in most countries today and will be coming out in the US next month. One essay in it is by yours truly, titled “Evolutionary Noise, Not Signal from Above”.

50 Voices of Disbelief (editors Russell Blackford and Udo Schüklenk, publishers Wiley-Blackwell) just went on sale in most countries today and will be coming out in the US next month. One essay in it is by yours truly, titled “Evolutionary Noise, Not Signal from Above”.

Two articles of mine appeared today in very different venues.

Two articles of mine appeared today in very different venues. A story of mine,

A story of mine,

Yours truly

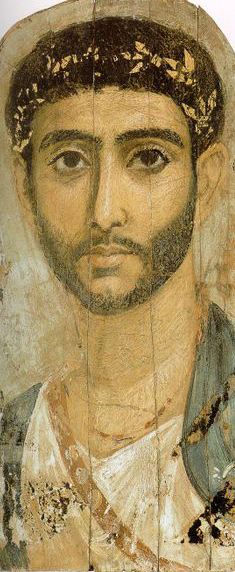

Yours truly  Two years ago, cancer struck me out of the clear blue sky at a moment in my life when I was gathering my strength for relaunching my research. I had just received two very hard-won grants after a lapse in funding that had essentially closed down my lab. The disease was at its early stages and I was spared the agony of chemotherapy, although some after-effects of the surgery (most prominently, severe fibromyalgia) are still with me.

Two years ago, cancer struck me out of the clear blue sky at a moment in my life when I was gathering my strength for relaunching my research. I had just received two very hard-won grants after a lapse in funding that had essentially closed down my lab. The disease was at its early stages and I was spared the agony of chemotherapy, although some after-effects of the surgery (most prominently, severe fibromyalgia) are still with me. I don’t believe in gods or an afterlife. Yet perhaps the only myth that can sustain us in such circumstances is Poul Anderson’s of the Ythrian Hunter God, a story that the medieval Greeks also told in their folksongs of Dighenís Akrítas: The Hunter will always prevail. The only thing you can do is give him a good hunt, for your own honor if not for his. Keep as much of your self and your life intact as long as you can. And do what you can to be long remembered, to leave that tiny footprint in the sand that will eventually get filled and smoothed away by the tide.

I don’t believe in gods or an afterlife. Yet perhaps the only myth that can sustain us in such circumstances is Poul Anderson’s of the Ythrian Hunter God, a story that the medieval Greeks also told in their folksongs of Dighenís Akrítas: The Hunter will always prevail. The only thing you can do is give him a good hunt, for your own honor if not for his. Keep as much of your self and your life intact as long as you can. And do what you can to be long remembered, to leave that tiny footprint in the sand that will eventually get filled and smoothed away by the tide.

The God Abandons Antony

The God Abandons Antony