by Larry Klaes, space exploration enthusiast, science journalist, SF aficionado. The article first appeared at Centauri Dreams.

Public Perceptions of ETI

Professional SETI researchers and other scientists tend to avoid the public perceptions about aliens, which they find to be full of undisciplined ideas and a tendency to buy into stories and reports about sightings of alien spaceships and their occupants. A fear of being lumped into the fringe realm of pseudoscience is among the top reasons why SETI has stuck with remote searches of distant star systems. However, there is a slowly opening acceptance that some ETI might send probes to our Sol system to observe us discreetly, perhaps in the Main Planetoid Belt or using nanotech devices or even smaller observing and data collecting technology scattered across Earth.

Several chapters of the book are devoted to polling the general public on the subject of alien life. Unrestrained by scientific parameters and paradigms, their theories and beliefs range from having aliens be the saviors of humanity to our destroyers. They also tend to be much more accepting of the idea that many ETI may already be here monitoring us.

In an ironic twist, the public often thinks of the physical appearance of alien beings as essentially humanoids with a large head and eyes, no visible ears, and slim bodies. On the other hand, scientists who focus on exobiology see life taking on many different forms on different worlds due to evolution. Nevertheless, because we know so little about life beyond Earth, a wide variety of viewpoints can be a welcome thing, as there are times when a different perspective on such a subject could be the key to discovery.

Among the most interesting papers in this collection were the ones where different human cultures interact with each other in space and time. In “Encountering Alternative Intelligences: Cognitive Archaeology and SETI”, Paul K. Wason looks at one of the fifteen humanoid species which have shared this planet with us, namely the Neanderthals. Although they existed in Europe around the same time with modern humans and even interbred with each other, their branch of the family tree died out roughly thirty thousand years ago. Clues from the archaeological record indicate that Neanderthals were quite different in many fundamental ways from current humanity despite being hominids which evolved on Earth. Even though their brains were a bit larger than ours, Neanderthal was not as sophisticated in many ways if we go by the evidence that has survived the ages. Regarding how scientists have learned as much as they do know about Neanderthals, Wason said: “Could it be also that one of the best ways of preparing for interstellar communication with other intelligences would be to engage in more study of how human intelligence works?”

Several centuries ago, there were two genetically related but otherwise very different human cultures which did interact with each other and for which we have extensive records of those encounters. In “The Inscrutable Names of God: The Jesuit Missions of New France as a Model for SETI-Related Spiritual Questions,” Jason T. Kuznicki, a research fellow at the Cato Institute, describes what happened when a group of Roman Catholic Jesuits sailed to North America starting in the Seventeenth Century to convert the native tribes living around the Canadian side of the Great Lakes region.

Armed with the tools of their religion, which included the presumptions of French philosopher Rene Descartes and Saint Thomas Aquinas that reason would inevitably bring everyone to the conclusion that the Christian God and souls exist, the Jesuit missionaries soon discovered that the Native Americans they met did not share these views or come to any of the same conclusions as the Jesuits thought would happen in matters of deities and the afterlife.

Here were fellow humans separated by a few thousand miles of ocean and yet the two cultures not only had wildly different views on many things, they also lacked the words of their languages to clearly get across their ideas on spiritual and religious matters. Now imagine what might take place between two entirely different species from separate worlds light years apart. Would an alien species even have a religion?

One aspect of Kuznicki’s paper which was not touched upon were the underlying motives for the Jesuits being in North America and attempting to convert the natives there: The French wanted to secure the New World for themselves from the competing British and Spanish powers. Having the Native Americans as allies would certainly help their cause, either through assimilation or coercion. Should an ETI contact us via interstellar transmissions or arrive in person at our world, this is one aspect of such an encounter that requires the study of historical precedents from our species. The scientists would assume the alien visitors are just explorers, but the historian might think otherwise. Even an ETI that came here with the purpose of doing what it thinks is good for us might have unexpected consequences for humanity.

The Question of Artificial Intelligence

Civilizations Beyond Earth does have its limitations. The focus is mainly on biological entities, which makes sense considering the authors. However, to not offer at least a few papers by some computer experts on artificial intellects, or Artilects as coined by Hugo de Garis, is hardly advancing our knowledge base of all scientific aspects of ETI. In this respect it is no better than focusing on radio as a means of interstellar detection and communication while ignoring Optical SETI and searching for Dyson Shells and alien probes in our Sol system.

Granted, there is a paper by William Sims Bainbridge titled “Direct Contact with Extraterrestrials via Computer Emulation”, which proposes the idea that a person could have themselves downloaded into a computer simulation as an avatar, or at least a psychological reproduction of themselves. Bainbridge envisions the avatars being beamed into space via radio waves to do the exploring and contacting with ETI.

Presumably this would have to be an enhanced version of the humans who choose to go this route, otherwise we encounter the limits of understanding an alien mind that would be little different than if we tried to comprehend an ETI with our own selves. Other chapters do deal with the complexities and difficulties in trying to communicate even basic concepts to an alien species, especially if we have few frames of reference. Would an Artilect with its faster computing speeds and much larger data storage do this better? Would sentience be required for this task or just a highly sophisticated simulation resembling awareness? Perhaps a revised edition of this book will add papers devoted to these questions concerning Artilects.

As Seth Shostak says in his article “Are We Alone?” regarding the Drake Equation, but which could also mirror what is missing and incomplete from this book:

“In other respects, [the Drake] equation might be too cautious. It assumes that all transmitting cultures are still located in the solar system of their birth. This ignores the possibility of colonization of other star systems (difficult, but not forbidden by physics), or the possible deployment of transmitting facilities far from home. In addition, it does not deal with the development of synthetic intelligence – thinking machines that would not be constrained to watery worlds orbiting long-lasting stars. In short, it makes the assumption that “they” are much like “us.”

For those who might argue that we may be unable to deduce the thought processes and motives of artificial minds far larger and faster than our own, the same could be said for any kind of biological alien species: Such beings could take on many forms and be just as inscrutable as an Artilect, yet that has not stopped many humans of all stripes on this planet from offering their views on organic ETI. One advantage with Artilects is that we can work towards actually creating or simulating them and thus have direct access to another intelligent mind.

Unfortunately, many people fear that Artilects could use their superior intellects to dominate or destroy humanity, just as they also expect advanced ETI to arrive in starships with similar goals. Whether that may ultimately happen or not, this general fear combined with a limited education on and cultural ridicule about the subjects relevant to SETI/METI have made their “contributions” to the reality that over half a century after the first serious SETI program, traditional searches continue in a largely sporadic fashion with limited funds, seldom expand beyond the radio and optical realms, and remain dominated by astronomers and engineers.

Human Expansion into the Galaxy

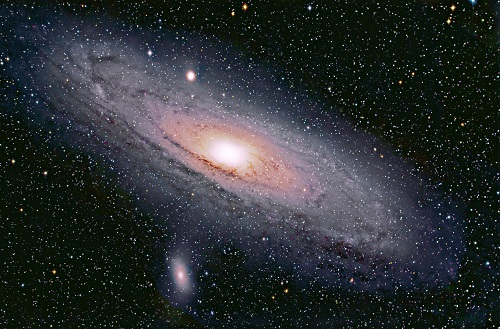

These views and paradigms also extrapolate to interstellar efforts such as Worldships, self-contained vessels carrying thousands of people on multigenerational journeys to other star systems. The goal of these Worldships is to colonize suitable planets and moons in the target system or at least collect resources from them before moving on to other galactic destinations.

How those who will remain onboard for perhaps many centuries will survive and adapt has been studied far more in the pages of science fiction than anywhere else, for obvious reasons. Will those who arrive at their intended worlds be radically different from their ancestors back on Earth? Will their interaction with any ETI they encounter diverge from the initial intentions of those who sent them off into the galaxy? As said earlier regarding Artilects, perhaps a revised edition of this work or a new book altogether devoted to very long term exploration and its consequences on those who make the voyage both aboard the Worldship and upon the places they settle will make inroads to answering these questions.

There is a strong desire or perhaps even a natural reaction to colonize any Earthlike exoworlds as part of some cosmic manifest destiny. Unless we terraform some barren rock, a planet similar to our own will be so not only in terms of size and environment, but also due to having life upon it. Even if none of the organisms on this alien world are sentient (and how exactly will we define that?), do we have the right to introduce terrestrial species there? If the situation was reversed and an ETI arrived at Earth to set up a new home, even if they desired a peaceful coexistence, imagine the reaction from humanity.

Even a robotic mission could cause unforeseen issues in the future. Already at this early stage in our expansion into space we have five probes and most of their final rocket stages heading beyond the boundaries of the Sol system into the wider Milky Way galaxy. Although none of them will be functioning by the time they could ever reach another star system, their very existence drifting and tumbling uncontrolled and aimless through deep space might one day become a problem for beings of which we are completely unaware at present.

We can declare that the galaxy is much too vast and these probes far too small to ever gain notice by any intelligences out there. We can say that any beings who could find these emissaries from Earth would have to be quite sophisticated and savvy with the ways of the interstellar realm and thus capable of dealing with a comparatively primitive, ancient, and inactive derelict from a species such as us.

In the end, however, the truth is that we do not yet know who or what is occupying the galaxy with humanity. We cannot say with certainty how an alien species might react and respond to an unexpected visitor from another world – though we can make some pretty good guesses as to how our civilization would behave in a similar scenario.

As we have already discussed with regards to SETI and METI, again the astronomical scientists and space engineering and technical fields often differ in their views on these matters compared to the anthropologists, sociologists, biologists, and historians. At least some of the gaps between the disciplines were bridged by the incorporation of messages and information packages on the Pioneer, Voyager, and New Horizons space probes. Whether these “gifts” will be recognized and understood by the recipients is yet another unknown factor, but they are a step in the right direction.

The issue of our physical intrusion into the Milky Way will become even more prominent and serious as we develop and launch probes – operated by Artilects most likely – designed to reach and explore other solar systems. In this case, humanity may receive responses from other intelligent beings in a matter of years or decades as opposed to millennia. What may happen and how our descendants might handle an ETI reaction will depend on how far our culture has come in terms of being more wide ranging and inclusive in our understanding of the Cosmos.

Civilizations Beyond Earth may be a slim book, but it is a good introduction to fields that need to be vital parts of any serious discussion of the scientific activities regarding extraterrestrial intelligences. If SETI and METI remain lopsided in their thinking, methods, and executions, the stars will likely continue to remain silent for the human species for a long time to come.

Not to know if we are either alone or one of many living beings in the Universe when we finally have the awareness and ability to answer this very important question would be a tragic shame, an affront to the very reason we have science and a civilized society in the first place. Let us not answer the L portion of the Drake Equation too soon from a lack of wonder, education, and funds.

We get attached to places and things. They define us as much as what’s inside our heads. We take handfuls of earth or tile fragments from our homes when we emigrate. We hold on to items of clothing that have become part of our bodies. We keep heirlooms, with their long stories of how they got made and handed down the generations. This knowledge is a major thread in the tapestry of civilization and in the definition of one’s self in a larger context. I had reason to think of this recently, when I lost something I loved.

We get attached to places and things. They define us as much as what’s inside our heads. We take handfuls of earth or tile fragments from our homes when we emigrate. We hold on to items of clothing that have become part of our bodies. We keep heirlooms, with their long stories of how they got made and handed down the generations. This knowledge is a major thread in the tapestry of civilization and in the definition of one’s self in a larger context. I had reason to think of this recently, when I lost something I loved. I decided to use sympathetic magic. After a search, I found a very different brooch, an antique Zuñi sunface made of silver, turquoise, coral, abalone and onyx. I put it on and willed someone to find mine, so that they would wear it as I wore this one, with its own long history and legacy of loving care.

I decided to use sympathetic magic. After a search, I found a very different brooch, an antique Zuñi sunface made of silver, turquoise, coral, abalone and onyx. I put it on and willed someone to find mine, so that they would wear it as I wore this one, with its own long history and legacy of loving care. Through the recent spike in the volume of tweets, I became aware of two things: 1) there is a Hugo award category called “Best Fan Writer” and 2) according to the rules, I’ve been eligible for it since 2008. At least in principle, because the real universe is significantly different.

Through the recent spike in the volume of tweets, I became aware of two things: 1) there is a Hugo award category called “Best Fan Writer” and 2) according to the rules, I’ve been eligible for it since 2008. At least in principle, because the real universe is significantly different.

To increase my already wild popularity, I penned two bookend articles that gore sacred oxen. A contribution to a Mind Meld at SF Signal about

To increase my already wild popularity, I penned two bookend articles that gore sacred oxen. A contribution to a Mind Meld at SF Signal about

I was elated to watch LotR consistently exceed my (initially not very high) expectations. But after The Hobbit, I feel dread at the thought that Jackson may decide to embark on The Silmarillion next. Perhaps he should read the folktale of the fisherman’s wife. Or read what Marx said about repeating history: the first time, it’s tragedy; the second time, farce.

I was elated to watch LotR consistently exceed my (initially not very high) expectations. But after The Hobbit, I feel dread at the thought that Jackson may decide to embark on The Silmarillion next. Perhaps he should read the folktale of the fisherman’s wife. Or read what Marx said about repeating history: the first time, it’s tragedy; the second time, farce.