Publish or Perish

Thursday, February 15th, 2007

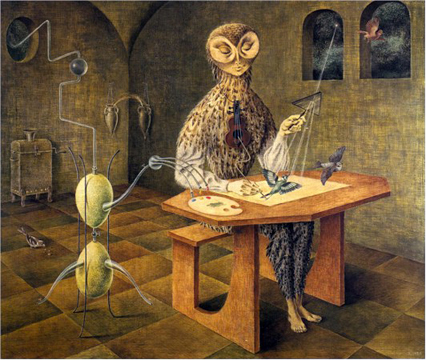

Remedios Varo: Creation of the Birds

Like all art, writing places harsh and divergent demands on the writer. We first have to sit for long stretches in a silent, empty room, and there struggle with the work like Jacob with his angel. Then we must step back, examine our creation dispassionately, and ruthlessly alter whatever we think falls short. To venture into the wider world, we are required to do work that has little to do with inspiration, although it, too, requires passion. We must write proposals, send letters, find agents, listen to criticism and adapt both our expectations and the work in response to it. And if we manage to navigate through all these shoals, we must be prepared for a significant portion of readers to dislike our work.

Until the early 20th century most authors paid to have their works printed or printed them on their own small presses. In other words, such luminaries as the Brontë sisters and Virginia Woolf would be considered “vanity authors” by today’s definition. Now, with the advent of e-books, print on demand and online publications, the boundaries are starting to blur and shift again. At the same time, both writers and readers are getting increasingly isolated in non-overlapping online universes dedicated to smaller and smaller subgenres.

Given these circumstances, what defines a writer? I have read informal writing that is of better quality than published works. Also, given the atomization of today’s readership, few writers can make a living exclusively on their writing unless they are recognized geniuses or can write very fast (there is, too, the occasional random lucky hit of a best-seller). The traditional advice to aspiring writers — found once in private letters, now in public livejournals — is to keep writing, no matter what. Unquestionably, writing is among the most creative and constructive hobbies. However, I noticed that these exhortations tend to come from people who are already published in official venues and/or have independent incomes.

After giving the matter a good deal of thought, I concluded that a writer is someone who writes with the goal of publication. Amusingly, two formidable institutions, the IRS and the NIH (National Institute of Health), agree with me. The IRS allows deduction of writing-related expenses if the writer can show that s/he attempted to publish the work, regardless of success. The NIH (and all agencies that fund research) allow investigators to list only published works on their grants. The Brontë sisters agreed as well: unworldly though they were deemed to be, they mailed their stories to London publishers the moment they completed them.

Publication rarely brings fame and fortune, especially in today’s climate of soundbites and short attention spans. Its major boon is that it takes us out of the lonely room where we stretch ourselves on racks of agony and ecstasy, out of the tiny ponds where social interactions overwhelm the primary objective of writing. It gives us perspective, it keeps us grounded. And it allows us to consider a particular work finished — finished enough to let go, like a child that grew up and finally left home.