A slightly modified version of this article appeared in Strange Horizons on October 3, 2005. I’m reprinting it because the cast of Star Wars VII was just announced — and people expressed surprise that only a single woman is among the main characters.

The second day that Revenge of the Sith opened, I left work early and like someone sneaking off to an illegal tryst, I went to see it.

I went hopefully but reluctantly, at the last possible moment. I’d enjoyed the brio of A New Hope and had been captivated by the darker hues of The Empire Strikes Back – though being Greek, I knew what “the surprise” was the moment I heard there was one. However, I had heartily disliked Return of the Jedi and Phantom Menace and was highly ambivalent about Attack of the Clones. I’m not bewitched by the endless battle scenes or the lightsaber pas-de-deux that eventually blur into sameness. I have immovable reservations about a universe geared to eleven-year old boys and their values – which exclude significant chunks of human experience but include the core belief that girls are icky and if a Jedi gets too close to them his lightsaber won’t ignite. Yet here I was, a scientist, a reader of Sophocles in the original and a woman nearing fifty, going to a matinee so that the room would be reasonably empty.

And in the darkness of the theater, I felt my eyelids prickle with anger and grief when young Anakin Skywalker, his mouth contorted with anguish, fell to his knees before the Emperor.

The ache persisted after I left the theater, so I started worrying it like a sore tooth. The plot, script and characters of the film flip-flop between the 10th and 30th centuries, between frothy action and portentous message, awash in hip-bruising clunkiness and jarring contradictions. But these shortcomings bedevil all Star Wars films, so that wasn’t the root cause. There’s the annoying Campbellian mishmash of iconic characters stripped of their specifics and reduced to facile shorthand (Anakin morphs into Icarus, Sampson, Achilles, Oedipus, Christ, Lucifer, Tristan, Othello, Faust… I’m sure I’ll find more if I put my mind to it). The degeneration of Padmé from Amazon to Puddle on the Floor was unbearable but I had sort of expected that from Mr. Lucas, who clearly feels comfortable only with virgins of both genders.

For a while, I thought that the ache came from my sense that Mr. Lucas, with his unlimited resources, could have woven a gripping story if only he’d move beyond his love of gizmos and lunchbox profits. We desperately need compelling stories. Anakin Skywalker’s fall, if told well, can hook right into the solar plexus because our culture has primed us for it: the fall of a great hero through pride, fear, rage or loss is a major theme (and, some argue, a definitive metaphor) of Western civilization.

Thinking over the constant mantra from both the Jedi and Sith Boys’ Treehouses (“Trust your feelings!”) I finally isolated what disturbed me so strongly that I started this essay on the eve of a grant deadline. I’d ignored similar twinges while watching the original Star Wars trilogy, because those films were lighthearted, lightweight romps. I cannot ignore it in Episode 3, which unfolds with Wagnerian solemnity and aspires to the mantle of Greek tragedy. There is a punitive spirit in the Star Wars prequels, as manipulative and controlling as the Dark Side it professes to abhor. Essentially, we are told that Anakin falls because… he loves his mate and so cannot gain the detachment required to become the Supreme Jedi Enforcer, a Buddhist Robocop.

To put it succinctly, Mr. Lucas advocates that only hierarchical interactions are legitimate and that partnerships between equals are toxic. Those between women and men are destructive and doomed. Those between men are acceptable only if based on the religious/military model of abject submission, in which alpha males apportion rewards at whim (there are no interactions between women in Mr. Lucas’ opus, as there is a single girl in each trilogy). In Star Wars, old men rule joylessly over a wasteland; girls die before they become those dreaded aliens, women; young men are left bereft and isolated – in Anakin’s case, literally walled off from all humanizing contact in his final incarnation as a demon in a can.

The presentation of such a universe as desirable even in fantasy by someone with Mr. Lucas’ influence is dangerous, at a time when people throughout the world are being turned into terrified cubicle drones and the US is hurtling towards government by a fusion of military, church and industry. We need different myths that topple this monolith, which combines gigantism born of industrial consolidation and institutional fusion with rampant social atomization. We have to reassert the virtues of thoughtful disobedience and wholesome self-will. To put it in Lucas-speak, guys who want their hugs should not be portrayed as weak or evil for wanting them.

The meta-thesis of Sith essentially asserts that submitting to the normal biological and social instincts catalyzes one’s destruction and ultimately makes one subject to depthless evil. It’s just a movie, I know. Still, it’s a vehicle for the shared stories that orient our thinking and help us imagine the possible. Today, facing a post-9/11 three-headed monolith that would have make Eisenhower’s military industrial complex look benign, we really need archetypes in our shared narratives who are rewarded for their capacity to bind people in assertion of wholesome common interest. Anakin’s story wants to teach us that a fate much worse than death awaits the fool who accepts love or tries to find an equitable community.

The boys in the bubble

I once saw an eerie picture taken at a Hasidic wedding. Separating the foreground from the background was the long curtain that keeps the genders apart. On the curtain fell the shadow of a young girl dancing, her braids (still her own, not yet a lifeless wig) swinging. At the front of the curtain, a boy was stretching his hand, trying to touch her shadow. Whenever I contemplate Star Wars, I’m reminded of that picture.

The human universe of the Star War prequels is a cold, airless locker. There are no families, no civic life beyond power politics, no artists or scientists, no (pre)occupation except endless wars which make as much sense as the Aztec campaigns to capture more victims for their altars. There is no song, no laughter, no tears until they spill like blood from hapless Anakin when his short tether is jerked once too often. There is no intimacy, no friendship beyond schoolboy camaraderie, no sex for either love or pleasure – though dismemberments abound, so it’s not the PG rating that caused this elision.

The only ones shown to raise children in Star Wars are the Jedi and the crèches that hatch the cloned boys bred for docility, who will become stormtroopers. Harry Harlow showed definitively what happens to primate babies when they’re deprived of caresses, something that the Jedi seem not to have registered during their long communion with the Force. Several power hierarchies in human history used the Jedi recruitment methods (removal from family, celibacy, forbidding of attachments) – most notably the Ottoman sultans. Not surprisingly, this created the janissary shock troops, not the samurai rangers Mr. Lucas wants us to believe naturally arise from such an upbringing.

The Jedi mumble Taoist-derived platitudes to prove that they’re on the side of Light but they are really a fusion of a rupture cult and a multinational corporation. To become “worthy”, prospective Jedi must suspend their own judgment and unquestioningly obey an authority whose teachings consist of silly psychobabble, endless hazing rituals and the sense of entitlement that comes from carrying arms. In the Jedi order, all normal mental or emotional responses are met either with the galactic version of the Amish Shunning (“You’ll be expelled!” screams Obi-Wan when Anakin tries to rescue Padmé during a battle) or with instructions to take cold baths (“Mourn do not!” intones Yoda when Anakin comes to him twisted with anxiety from having nightmares about Padmé dying). Anakin is supposedly not just the most powerful wielder of the Force but also a pivot, yet the Jedi treat him like a passive asset or an unruly horse. At least the Sith are frank about what they want and how they go about getting it.

And to what great purpose is Anakin’s “high midichlorian count” harnessed? He is turned into a fighting machine for the status quo, just as Wolverine of the X-Men is made into a weapon even though his gift is for healing. The powerful realized long ago that the most reliable way to produce killer automatons is to separate young boys from the other gender and from the part of themselves that questions, does not split thinking from feeling – and fights from inner conviction, not thwarted affection and vaporous promises of glory. Anakin does not need to carry destructive genes. The Jedi have implanted in him such abject fear of natural reactions and processes that he is bound to detonate a landmine in any direction he steps.

The Jedi philosophy does not lead to swashbuckling exploits, but to Wounded Knee and Buchenwald, to young men flying airplanes into buildings. People are systematically dehumanized in Star Wars, treated as interchangeable ciphers. We never see what happens to the civilians. The cloned soldiers never take off their helmets, making it convenient to forget that they are still human inside those plastic uniforms. Hacking off body parts appears the sole legitimate response to disagreement in Star Wars: there is no visible price for it, if committed by a Jedi – and by virtue of the lightsaber it’s always neatly bloodless.

Yet there is an interesting exception to this coyness: Obi-Wan – the embodiment of all Jedi virtues – first mutilates his apprentice, his adopted younger brother, the comrade who repeatedly saved his life, then leaves him burning alive. Granted, the plot dictates that this charred stump must survive to menace his children as a cardboard villain in the sequels. However, Mr. Lucas could have achieved story continuity without making a snuff scene about what must happen to those who question authority.

All this desolation springs from the glorification of infantile dualism and the mistrust of complex human interactions. “Be afraid! Desire will make you betray duty!” pronounce the Jedi in their quest for tractability – and Anakin rips himself to shreds over the false conflict. In Dune, Paul Atreides becomes a genuine Prometheus, because he wrenches control of his strings from the Bene Gesserit and assumes full responsibility for the jihad he unleashes. Anakin, on the other hand – ardent, naïve, frantic for approval – never attains free will or the charisma and seductive grandeur of a true Lucifer, despite his off-the-charts Force readings. Callously treated by all his surrogate fathers, that torn boy is not a failed Messiah but a pawn. In the end, he follows the Jedi teachings to their logical conclusion, and creates a universe of total order by systematic slaughter. It would have been better for him and for the galaxy if he’d been Iroquois: the women of that nation could forbid their men from taking part in unjust wars.

Catching girl cooties

If men of the Star Wars universe are held in cages of rage and fear, its lone girls are ignored until the boys need an Angel in the House (Jango Fett at least is honest, bypassing women altogether). The token girl in the Lucas universe faces a lose-lose proposition. She cannot do anything by and for herself; her sole function is to act as an impotent hand-wringing conscience for the men. However, this function is worthless since non-warriors in Star Wars are treated as subhuman, despite the lip service to justice and compassion. As Éowyn says to Aragorn: “All your words are but to say: you are a woman, and your part is in the house. But when the men have died in battle and honour, you have leave to be burned in the house, for the men will need it no more.”

Just as the boys in Star Wars are given the false choice between glory or love, the girls are given the thankless task of being feisty but unthreatening, without any guarantee of clemency for good behavior. Worse yet, since there is only one female per Star Wars trilogy, she has to be mother, sister, lover all rolled into one. That, of course, is a no-no because it blurs the sacrosanct divisions between virgin and whore – and also because it implies dominance (to underline the transgression, Padmé is explicitly older and of higher rank than her tercel boy husband). The girl is a threat to the boy’s purity of purpose, an Eve in the making; when she crosses the sexual and emotional boundary, she is speedily dispatched, Ophelia-style, abandoning her defenseless children – the girl condemned to be left untrained in her power, the boy slated to undergo the brutalization already meted out to his father. Once again, Mr. Lucas is swift to punish those who partake of the fruit of knowledge and threaten to become independent moral agents.

There is something almost prurient in this punitive puritanism, but it also points to a tremendous failure of the imagination. In a universe with advanced prosthetics, sentient AIs, cloned armies and faster-than-light travel, women have no access to contraception and still stand to lose their jobs when they get pregnant, like Japanese office girls. Mr. Lucas not only cleaves to the tenets of the nuclear family, but explicitly to its fifties version. Yet even within Mr. Lucas’ tiny menu of female choices there is one compelling alternative. Predictably, he toys with it but eventually lets it lie fallow, as it would subvert his emphasis on the dangers of loving women and the need to choose the disembodied rewards of monastic male bonding.

In Renault’s The King Must Die (hardly a feminist anthem), the Amazon Hippolyta agrees to a parley with Theseus, “one king to another”. You are a queen, he corrects her. No, she replies, I’m a king like you… a woman king. Hippolyta becomes the irreplaceable center of Theseus’ life because she is his equal. Would that Mr. Lucas had been “radical” enough to make Padmé as powerful as Buffy, the slayer and lover of vampires, or as resourceful as Guinevere in the recent revisionist remake of King Arthur. It might even have helped his anemic storyline.

If a girl cannot have adventures of her own, she can at least be the boy’s partner in his. This allows a non-hierarchical interaction in which real stakes are involved, with room for both intimacy and camaraderie, both vulnerability and heroics. For a brief moment in Attack of the Clones there is hope for such an alliance, in the arena confrontation. There, Padmé becomes Anakin’s charioteer (a position reserved for the hero’s male lover in the sagas) and she proves formidable in battle despite her lack of a lightsaber. It is telling that this segment contains the sole believable kiss that the two exchange.

Such partnerships cut right through the hoary male bonding of the Jedi and their ilk and are truly subversive. Love that spurs people into action is rightly feared by power hierarchies, because it strides across boundaries considered immovable. Anakin’s original hothouse infatuation in Attack of the Clones is not really dangerous to the status quo – in fact, it acts as a convenient pressure release valve. At the end of that episode, though, Anakin makes a conscious covenant with Padmé unlike his agreement to enter into the Jedi order, for which he was too young to give informed consent.

The stories of André Norton and the wuxia films of Yimou Zhang and Ang Lee explore this mode by making the genders often conflicted allies but always equal in prowess. In contrast to the passivity and distance of pedestals, partners guarding each other’s back are fully engaged with each other and with the task at hand. The private and public duties fuse into a seamless whole, reinforcing rather than weakening each other. However, even second-hand heroism for women is not an option in the Lucas universe.

Revenge of the beta males

I once saw a cartoon of a bunch of cave men, throwing spears at a saber tooth tiger that has already mauled several. One of them is saying to another, “I can’t imagine how stupid the beta males must be feeling, left behind with the women.” This encapsulates the attitude of the Jedi and Mr. Lucas, and also serves as the goad used in boot camps. It’s a neat trick, of course, because forswearing the love of women as polluting does not turn boys into superheroes or rebel leaders, it merely makes them angry and needy enough to unquestioningly become cannon fodder. Even doofy Peter Parker figures this one out in Spiderman 2.

If the Jedi teachings are inadequate even during times of strife, they are even worse recipes for living when the exploits must come to an end (maybe that explains the need for constant upheavals in the series). Men and women who are fully grown humans can pick up weapons during rebellion or defensive war and then can lay them down and go back to being bards, healers, explorers, craftspeople, parents. The American revolution was all about yeomen standing up to elite troops — as was the Vietnam war. When the din of battle ceases, people can think and start asking questions. The Jedi need to retain their privileges as a self-appointed elite caste and the clones, solely bred for killing, cannot stand down. So if one war ends, a new one must be started. Integration of professional soldiers has always been a major problem in human societies. In Star Wars, the slow pace and hard labors of peace appear as glamorous as doing laundry when juxtaposed to the duels and battles, no matter how pointless these are. But those who have seen real war and its aftermath know how far removed it is from the balletic, antiseptic melees featured in Star Wars.

The original Star Wars trilogy was a gentler, kinder place than the prequels in part because the workings of love or peace did not rear their ugly heads. But Anakin wants affection as well as a purpose worthy of his powers. When the abuse keeps falling on him like Chinese water torture despite his heroic efforts, he grows mutinous – so he and his Jocasta must be made into examples. By making Anakin the focus of the sextet, Mr. Lucas invalidates the lightheartedness, verve and hopefulness of the original trilogy. We are meant to judge the boy weak in resolve, open to temptation because he’s concerned for his mother and his wife, in need of redemption by the son who achieves the state of holy eunuch that eluded his sire.

But the dilemma that breaks Anakin is a decoy, to distract him from realizing that he’s being used. His real fall comes when, goaded past endurance, he attains the detachment so dear to the Jedi and stops seeing people as individuals. His tragic error is not that “he loveth too well” (as Mr. Lucas posits) but, on the contrary, that he doesn’t trust his lover enough to heed her counsel. His primary loyalty is always to his masters, not to his partner – and he still gets seared to ash for not saying “Yes, Master!” often enough. Nor is he truly forgiven: in the end he isn’t reunited with Padmé, but sentenced to spend eternity with Yoda. As for Padmé, there is little left to grieve over. Except as an incubator, she really dies at the end of Episode 2.

In The Matrix, Neo and Trinity go down together in battle, bonded partners to the bitter end. A sludgeful of mystic bombast bubbles through that trilogy, but at least Trinity is never reduced to Mary Magdalene. Perhaps the difference is that the Oracle issuing the portents in The Matrix is a confident, rebellious, ornery old woman, rather than a chorus of frightened, rule-bound, prissy old men. Ursula LeGuin’s Roke wizards start out in a configuration almost identical to that of the Jedi in her early Earthsea novels – but by the end of the cycle, braver and wiser than the Jedi, they decide to open their doors to the world, Their choice guarantees that they remain forces of renewal, rather than oppression.

Anakin should have listened to his mate, and opted out of the brutal, pointless competition for teacher’s pet. He could still have become the hero and savior he so craved to be: he could have gone with her to free the slaves on Tatooine (even if that meant giving up his nifty lightsaber). They’d probably have failed and he might go through the agony of watching her die – but, as King Théoden says, that would be an end worthy of remembrance. Or, if she could not sway him from his ruinous path, she should be the one to fight him, Galadriel to his Fëanor, instead of fading away like a Victorian consumptive.

There is a man in Star Wars who gets it all and he is the one who follows Padmé’s injunction to step out of the imprisoning box. That is Han Solo, not a Jedi but a commoner, a freelance mercenary who does not care about belonging to boys’ clubs. In The Lord of the Rings, too, it is not the hero Boromir but his younger brother Faramir, the reluctant warrior, the scholar scorned by his father, who survives and wins Éowyn. Tolkien, despite his unabashedly Manichean view of the world, is more nuanced, progressive and humane than Mr. Lucas.

After Revenge of the Sith, I for one cannot look at the praying mantis mask of Vader without superimposing on it the haunted eyes of the boy entombed within that carapace, still smoking with need and loss. I cannot watch the films without recalling how his mentors tormented and betrayed him, turned his humanity against him, leading him to wreak terrible ruin in his turn. Of the girl I can only see a pale ineffectual ghost. Episodes 2 and 3 of the Star Wars prequels are a cautionary tale about the dangers of wanting to be fully human, tracts on the need for unquestioning submission to authority. Armies, fundamentalist churches and corporations should add them to their teaching manuals. The rest of us should go and create subversive tales of universes not threatened by complexity, wholesome tribal affiliations or plain garden-variety affection.

Related articles:

Reflections on the New Star Trek

Cameron’s Avatar: Jar Jar Binks Meets Pocahontas

The Multi-Chambered Nautilus

“As Weak as Women’s Magic”

A Plague on Both Your Houses“Are we Not (as Good as) Men?”

The Persistent Neoteny of Science Fiction

Ain’t Evolvin’: The Cookie Cutter Self-Discovery Quest

Fresh Breezes from Unexpected Quarters

Hagiography in the SFX Age: Jackson’s Hobbit

Where Are the Wise Crones in Science Fiction?

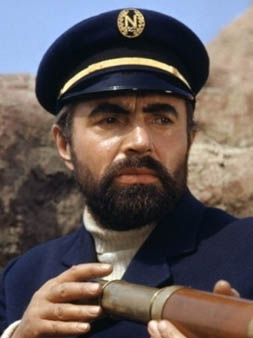

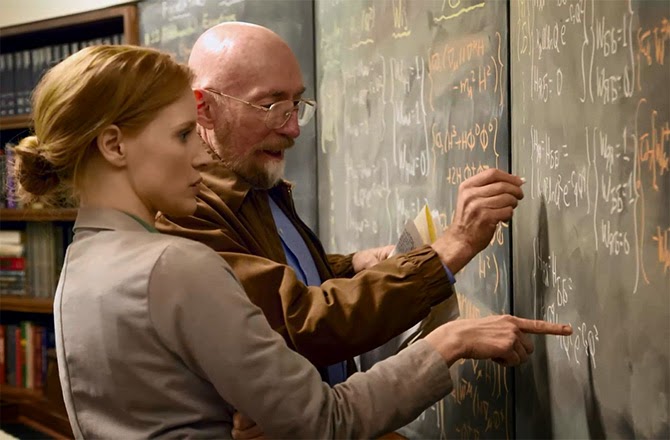

Images: 1st, Anakin Skywalker (Hayden Christensen) in Revenge of the Sith; 2nd, Mei (Zhang Ziyi) and Jin (Kaneshiro Takeshi) in House of Flying Daggers

Imagine you’ve landed on an earth-like planet. You can live there without erecting domes, but there’s a gas dissolved in the atmosphere that makes you slightly ill. You rarely feel fully yourself. You have some difficulty gathering your thoughts, you have to take time to parse your every action. You spend excessive amounts of effort trying to get basics done.

Imagine you’ve landed on an earth-like planet. You can live there without erecting domes, but there’s a gas dissolved in the atmosphere that makes you slightly ill. You rarely feel fully yourself. You have some difficulty gathering your thoughts, you have to take time to parse your every action. You spend excessive amounts of effort trying to get basics done.

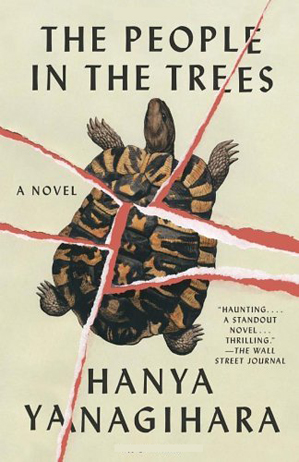

Athena’s notes: An exploration of immortality that starts similar to Yanagihara’s but goes in a totally different direction is Le Guin’s

Athena’s notes: An exploration of immortality that starts similar to Yanagihara’s but goes in a totally different direction is Le Guin’s