by Calvin Johnson

I’m delighted to once again host my friend Calvin Johnson, who earlier gave us insights on Galactica/Caprica, Harry Potter, The Game of Thrones, Star Trek: Into Darkness, Interstellar and The Grace of Kings.

Is science fiction really the literature of possible future histories? Or is it a veiled metaphor for the author’s own time and place, safely hidden behind a charade of robots, rocketships, and aliens?

I vote for the latter. Even science fiction that claims to be nothing more than escapist fun can be easily mined for political, social, and philosophical themes reflecting the view out the author’s window. Of course, this might be because every nation has a dark side and hidden sins, so even the most modest of inquiries can throw up menacing shadows.

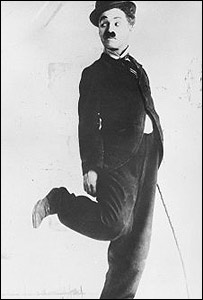

It’s sometimes easier to perceive this outside of one’s own blind spots. As an example, consider Liu Cixin (instant lesson in Mandarin: it’s pronounced Lyoo Tsi-shin, and Liu is the family name). He’s one of the most popular authors in China these days, and he’s recently come to the attention of English-speaking audiences with the first volume of a trilogy, The Three-Body Problem, which won the 2015 Hugo.

Liu has apparently stated that his novels are not political commentaries, and given how Chinese premier Xi Jinping is cracking down on dissension, I can’t blame him for such claims. I’m pretty sure Premier Xi does not read this blog, so I can state openly without worrying for Mr. Liu’s safety: this is not actually true. Both The Three-Body Problem and its sequel, just published in English, is shot through with current political and social concerns.

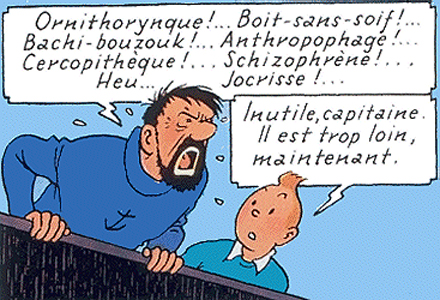

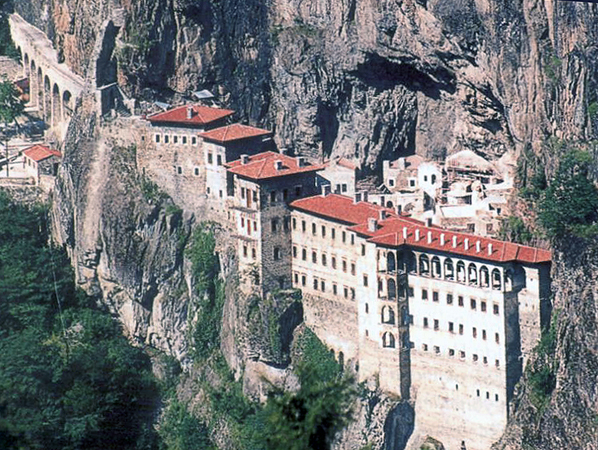

The Three-Body Problem opens with the floridly described horrors of the Culture Revolution (described in China nowadays as “the ten years of turmoil”). The embittered daughter of one of the victims ultimately betrays the human race to menacing aliens from the Alpha Centauri system, whose triple suns’ chaotic motion continually erases notions of progress and stability.

The second book of the trilogy, The Dark Forest, tells how humankind faces impending invasion by a far superior culture and how it plays out over the centuries it takes for the “Trisolaris” to arrive. Humans are already being spied upon by sophons, higher-dimensional artificial intelligences, so we have to assume all conversations and communications are being monitored and intercepted. (No, no relation to modern day politics whatsoever.) The only refuge is in one’s private thoughts. Out of desperation humankind appoint four men to create secret plans to resist the Trisolaris, men whose orders, no matter how outlandish, must be obeyed without question.

Meanwhile, humanity must struggle against the doomsayers and Escapists who believe the only chance for survival is to abandon home and emigrate, and those who secretly collaborate with the enemy. Worse, one by one we learn that all the secret plans for resisting the enemy involve Pyrrhic victories almost as bad as the invasion itself.

Meanwhile, humanity must struggle against the doomsayers and Escapists who believe the only chance for survival is to abandon home and emigrate, and those who secretly collaborate with the enemy. Worse, one by one we learn that all the secret plans for resisting the enemy involve Pyrrhic victories almost as bad as the invasion itself.

Let me pause here to say to any of you thinking this sounds a bit over the top: read recent Chinese history. Imagine if today the Zetas and other narco trafficking gangs invaded the US, defeated our military and at gunpoint forced us to sell drugs legally and openly–and you’ll have exactly the situation China faced with Western nations, led by British Queen “El Chapo” Victoria, a century and a half ago. And after that things really went down hill.

In light of that history, it’s not as shocking that by the end of The Dark Forest, the last remaining secret planner and the central figure of this volume, Luo Ji, has figured out the solution to the Fermi Paradox (“where are all the aliens?”), and boy, is it a chilling, paranoid answer, something so dark it even frightens the Trisolaris. Where this all leads will have to wait, for those of us who don’t read Chinese, for the release in 2016 of the final volume, Death’s End.

Chinese novels often do not translate seamlessly into English and English novelistic sensibilities, and this is very much so for Liu’s work. The prose, in English, caroms between between florid, overly precious metaphors and boxy, inedible infodumps. Characters are thinly drawn, women doubly so. Although I don’t see it as a fault, I suspect many English-language readers will struggle with the stream of Chinese names, even with the helpful footnotes and list of characters.

Nonetheless, I thought The Dark Forest a stronger novel in many ways than The Three-Body Problem. The themes and conflicts felt more natural and less forced than those in the first volume. (It did not help that the chaotic astrophysics claimed for the Alpha Centauri system in the first volume struck me as highly overblown.) The story arc, revolving around Luo Ji even when at far aphelion, was tighter. Most importantly, The Dark Forest, with its solution to the Fermi Paradox, comes far closer than its competitor to the putative “novel of ideas” science fiction nominally presents. Most of the “ideas” in science fiction I find shallow. Ask yourself: after reading Heinlein, did you really long for junta rule, or the joy of incest? Do you really remember any of the soporific dialectic debates among Asimov’s robots?

My own conclusion is that science fiction is not a literature of ideas, but it is a literature about our response to ideas. That’s the case here too. The Dark Forest is not that much deeper intellectually, but the mad secret at the heart of the novel, and what it says about us and the scarred fears we carry with us, is more chilling than any bat-winged tentacle-faced monster Lovecraft dreamed up. Ji’s discovery whispers of the terrors that almost destroyed us during the Cold War, that did destroy millions of lives during the twentieth century.

And have we shaken it off? Reflect on events of the past ten years, or even just the past year. I say any statement that Liu’s trilogy is apolitical is an untruth; but in his defense, one can convincingly argue it’s not just about Chinese politics. It is about living deep in the shadows of the dark forest of the human condition, everywhere, and in every time.

And have we shaken it off? Reflect on events of the past ten years, or even just the past year. I say any statement that Liu’s trilogy is apolitical is an untruth; but in his defense, one can convincingly argue it’s not just about Chinese politics. It is about living deep in the shadows of the dark forest of the human condition, everywhere, and in every time.

Athena’s postscript: I haven’t read Liu Cixin’s novels, so I can offer no opinion of either the works themselves or their translation. However, my views on SFF as “the literature of ideas” are contained in The Persistent Neoteny of Science Fiction and To the Hard Members of the Truthy SF Club.

Images: Top, comparison of size and star type between Sol and the three stars of the Alpha Centauri system; middle, Cultural Revolution poster; bottom, Liu Cixin.