“…they see women as radiant and merciless as the dawn…” — Semíra Ouranákis, captain of starship Reckless at planetfall (Planetfall).

“…they see women as radiant and merciless as the dawn…” — Semíra Ouranákis, captain of starship Reckless at planetfall (Planetfall).

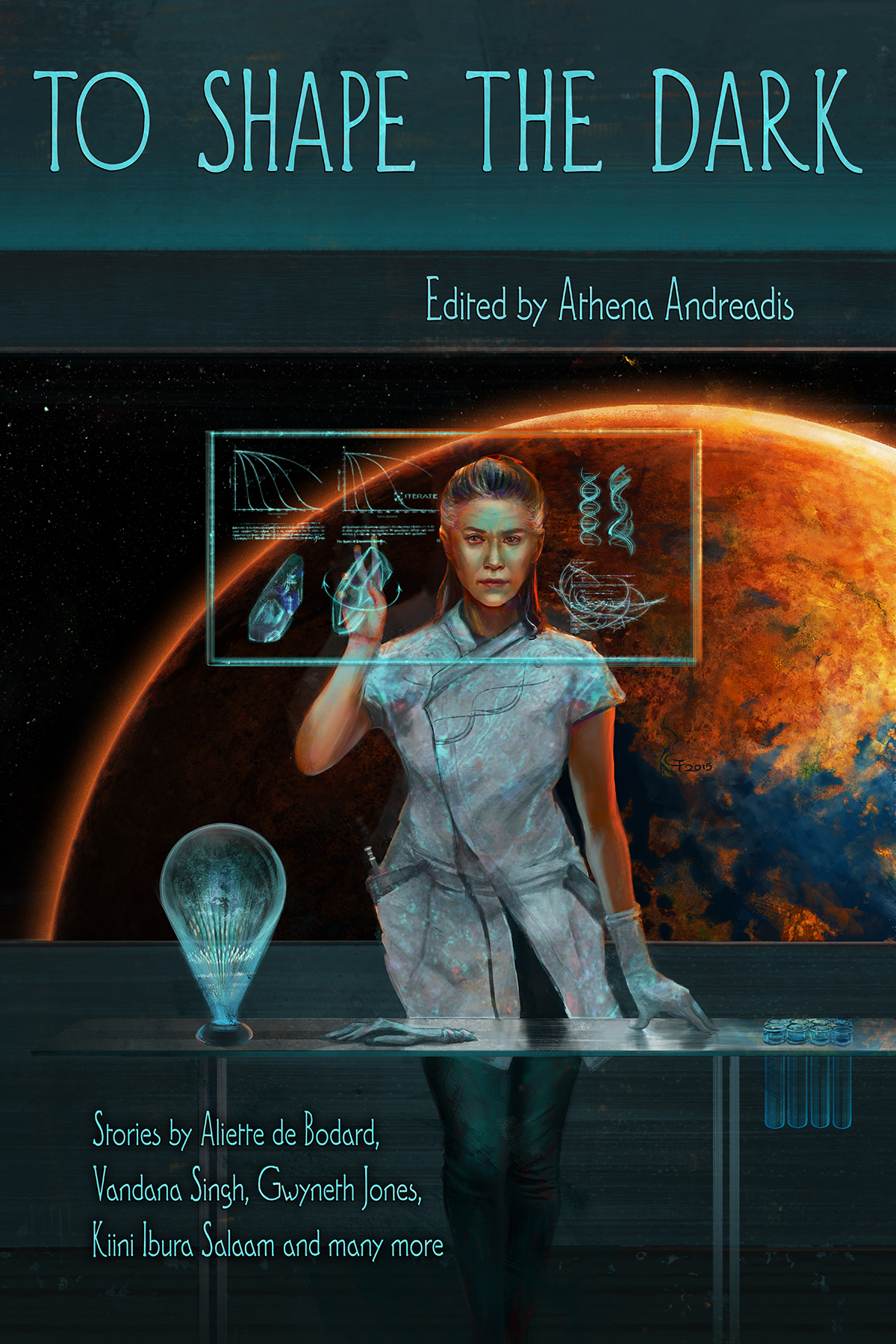

As before, I decided to whet appetites. Below is not only the TOC of the anthology, but also the opening bars of each movement that’s part of this symphony.

All the protagonists are scientists who transcend the usual SF clichés about that vocation, especially when undertaken by women. I won’t say more, the snippets speak for themselves. For those eager for more, the projected launch is early spring 2016.

To Shape the Dark

Athena Andreadis – Introduction: Astrogators Never Sleep

Constance Cooper – Carnivores of Can’t-Go-Home

M. Fenn – Chlorophyll is Thicker than Water

Jacqueline Koyanagi – Sensorium

Kristin Landon – From the Depths

Shariann Lewitt – Fieldwork

Vandana Singh – Of Wind and Fire

Aliette de Bodard – Crossing the Midday Gate

Melissa Scott – Firstborn, Lastborn

Anil Menon – Building for Shah Jehan

C. W. Johnson – The Age of Discovery

Terry Boren – Recursive Ice

Susan Lanigan – Ward 7

Kiini Ibura Salaam – Two Become One

Jack McDevitt – The Pegasus Project

Gwyneth Jones – The Seventh Gamer

Let the storytelling begin:

Constance Cooper – Carnivores of Can’t-Go-Home

After all our weeks of travel, those final few miles in a wagon drawn by ox beetle seemed the longest of all. The wagon reeked of peat, and the ox beetle periodically dug its claws into the mud and surged forward to free up the wheels. McMurrin, our dour driver, actually managed a chuckle as his insect’s motions flung me and Gwen back and forth. Gwen kept her pet project, a custom high-eye, cradled protectively in her arms.

Every moment I knew that we were getting closer and closer to haunted, hated Can’t-Go-Home Bog, right on the southern fringe of settlement, where no other botanist had ever set foot.

M. Fenn – Chlorophyll is Thicker than Water

“Afternoon, Dr. Yamamoto.” The old woman looked up from the flower seed display she had been studying while waiting.

“Afternoon, Billy. How’s your mother?”

“Good! She told me to thank your partner for the lotion, if I saw you. Her hands are much better.”

“I’ll tell Hina you said so. And how’s your skin doing?”

The boy blushed. “Fine.”

She smiled kindly. “Good. I’ll tell her that, too. Did my order come in?”

She trundled her round frame closer to a display of wind chimes. Hina would like one of these new copper ones, she thought, brushing her calloused hand against the metal pipes. A ceramic frog mounted on the top remained stoic as the chimes tinkled.

Jacqueline Koyanagi – Sensorium

Yora spends her first night in cultural realignment training thinking about the isolation of a life lived between stars.

The Tagli came to Ila, her planet, ten years ago, having crossed unthinkably vast distances in slow increments, bodies and vacuum separated by a mere skin’s breadth of material. Full generations had passed with no knowledge of ground and sky. And then they came, a bombardment of unfamiliar life on Yora’s planet, their twisting ships suspended over fourteen cities like itinerant gods.

Kristin Landon – From the Depths

“Rinna!”

Rinna Heinonen turned, one hand on the hatchway that would let her out of the family quarters, and suppressed a groan. Her fifteen-year-old daughter stood across the small common room from her—in her iso suit, fluorescent orange, its hood and mask dangling around her shoulders.

Rinna sighed. “Just where do you think you’re going?” Sealed in, Petra would be ready to leave Hokule’a with a minimal chance of contaminating the air and sea with her human DNA and microflora.

Petra’s long mass of tight braids was tied back in a ponytail, and she carried her backpack. She smiled tentatively at her mother. “I thought you might need a hand today.”

Shariann Lewitt – Fieldwork

“Grandma, do you think Ada Lovelace baked cookies?” We were in her kitchen and the scent of the cookies in the oven had nearly overwhelmed my childhood sensibilities.

“I don’t think so sweetie,” Grandma Fritzie replied. “She was English.”

“Oh. Mama doesn’t bake either.”

Grandma Fritzie shook her head. “There wasn’t any good food when she was young.”

“Did her Mama bake?”

“Maybe. But not after they left Earth. They only had packaged food on Europa, and no ovens or hot cookies or anything good. That’s why your Mama is so tiny. We’re going to make sure you get plenty of good things to eat so you grow up big and strong.”

Vandana Singh – Of Wind and Fire

I have been falling for most of my life. I see my village in dreamtime: an enormous basket, a woven contraption of virrum leaves and sailtrees, vines and balloonworts, that drifts and floats on the wind. On the wind are borne the fruits from the abyss, the winged lahua seeds that always float upward, and the trailing green vines of the delicious amala — windborne wonders that give us sustenance. But the village is always falling. Slowly, because of the sails and balloonworts, but falling nevertheless. We hang on the webbing, the children and babies tethered, shrieking in joy — and we tell stories about what might lie below.

Aliette de Bodard – Crossing the Midday Gate

Dan Linh had walked out of the Purple Forbidden City not expecting to return to it – thankful that the Empress had seen fit to spare her life; that she wasn’t walking to her execution for threefold treason. Twenty years later – after the nightmares had faded, after she was finally used to the diminished, eventless life on the Sixty-First Planet – she did come back, to find it unchanged: the Midday Gate towering over the moat; the sleek ballet of spaceships between the pagodas and the orbitals; the ambient sound of zithers and declaimed poetry slowly replacing the bustle of the city at their backs.

Melissa Scott – Firstborn, Lastborn

It has been more than a decade since I first set foot in Anketil’s tower, and three years since she gave me its key. It lies warm in my hand, a clear glass ovoid not much larger than my thumb, a triple twist of iridescence at its heart: that knot is made from the trace certain plasmas leave in a bed of metal salts, fragile as the fused track of lightning in sand. Anketil makes the shapes for lovers and the occasional friend when work is slow at the tokamak, preserving an instant in threads of glittering color sealed in crystal, each one unique and beautiful, though lacking innate function. It’s only the design that matters. I hold it where the sensors can recognize it, and in the back of my mind Sister stirs.

Anil Menon – Building for Shah Jehan

“Thermoplastic,” said Kavi, working her mouth as she considered our architectural model, “is not sand.”

I relaxed. If that was her biggest grief, then we were in good shape for tomorrow. It was almost one-thirty in the morning, which meant that only eight hours remained before our final projects were due.

Knock on the door. Then Zeenat popped her head in, her round sleepy face indicating what she was about to ask. “Chai, guys?”

“Yes,” said Kavi.

“I’d like to look over the drawings one more time,” I said. “Make sure it’s habitable. The design is only—”

“She’s trying to say no,” Kavi explained to Zeenat. “You go ahead.”

“So let Velli look over whatever needs to be looked over, we can go have chai.” And then Zeenat added, “My treat.”

C. W. Johnson – The Age of Discovery

It was a milestone, no matter what, and so the lab celebrated. Roberto looked abashed as they toasted him. “Hey, guys,” he said, fidgeting, “I should get back to work.” Everyone laughed. Their supervisor Ms. Thalivar called out, “How fast can you do the next thousand?” and Roberto said, “Well, now that I’ve finally got the hang of it…”

Luo Xiaoxing, the publicist sent over from Shanghai, went around taking images and videos. She squeezed past a couple of technicians and stopped at Edith’s station with her all-in-one raised. “Do you mind?”

Edith shrugged. “The company sent you. But shouldn’t you…?” She pointed with her chin to Roberto.

Terry Boren – Recursive Ice

1. Heuristic

The afternoon wind, cool and rain scented, lifted Bret’s hair away from her neck as she gazed down at the Isar where it slid green and quick beneath the bridge. Her vision was blurred and distorted one moment, absolutely clear the next. Her palms rested gently on the pitted granite of the railing. It was familiar, safe. But though she had done her graduate work at the Planck Institute in Germany, years before, she still could not remembered what she was doing in Old Munich. Something to do with her work? She touched her face, probing gently at the swollen cheek. The eye itself seemed undamaged, though the area around the left socket and the left side of her face were bruised. The cheekbone probably had been cracked. Her cheek was wet, and pain made the eye tear again, distorting the green park along the green river. The wind was picking up. Hoping to reach shelter before the storm broke, she continued across the bridge toward Mariahilfplatz and the frozen spire of its church.

Susan Lanigan – Ward 7

The man from HR was speaking. She could not recall his name, even though it glinted from the bronze-coloured badge he wore below his left lapel. That was because the badge always seemed to catch the intense sunlight coming in through the south-facing glass wall, to which the HR man himself seemed immune, even though it was hitting the back of Vera’s neck so precisely that she felt as if the rays were burning a line on her skin above her collar. Both room and man were unfamiliar to her. Employees from the medicinal chemistry division of Gleich Enterprises rarely got summoned here. But her presence was “imperative”, she had been told, her offence too severe to be overlooked this time.

Kiini Ibura Salaam – Two Become One

Aversion:

Meherenmet glared across the room as she watched an attendant feed Amagasat dates and tiny sips of beer from a serving tray. Disgust spiked through her body. She looks like an aging child, Meherenmet thought.

Morning light filtered into the eye-shaped antechamber, bathing Amagasat in a soft glow. She shimmered in her iridescent blue robe and golden collar and wrist cuffs—all intentionally worn, Meherenmet thought, to boast of her success. But Amagasat’s tremors—that fierce trembling of her hands—overshadowed her finery. Meherenmet doubted that Amagasat could still dress herself, or even attend to her own elimination.

Jack McDevitt – The Pegasus Project

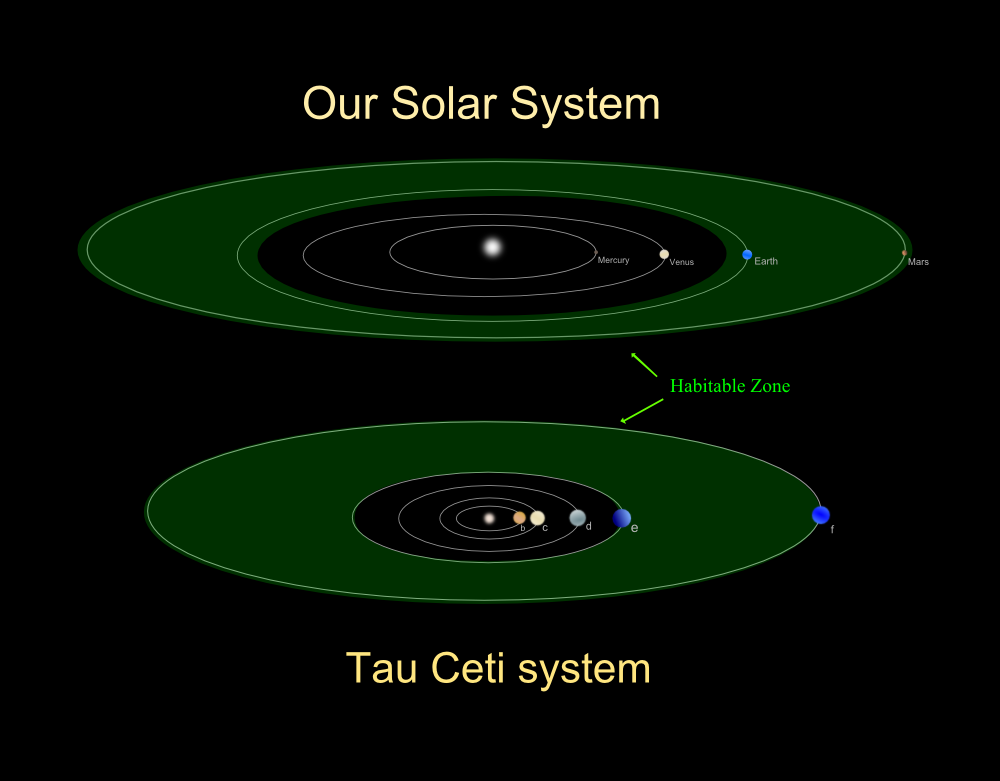

I was sitting on the porch of the End Times Hotel with Abe Willis when the message from Harlow came in: Ronda, we might have aliens. Seriously. We picked up a radio transmission yesterday from the Sigmund Cluster. It tracks to ISKR221/722. A yellow dwarf, 7,000 light-years out. We haven’t been able to break it down, but it’s clearly artificial. You’re closer to the Cluster than anybody else by a considerable distance. Please take a look. If it turns out to be what we’re hoping, try not to let them know you’re there. Good luck. And by the way, keep this to yourself.

“What is it?” asked Abe.

“Aliens.”

Gwyneth Jones – The Seventh Gamer

The Anthropologist Returns To Eden

She introduced herself by firelight, while the calm breakers on the shore kept up a background music – like the purring breath of a great sleepy animal. It was warm, the air felt damp; the night sky was thick with cloud. The group inspected her silently. Seven pairs of eyes, gleaming out of shadowed faces. Seven adult strangers, armed and dangerous; to whom she appeared a helpless, ignorant infant. Chloe tried not to look at the belongings that had been taken from her, and now lay at the feet of a woman with long black hair, who was dressed in an oiled leather tunic and tight, broken-kneed jeans; a state-of-the-art crossbow slung at her back, a long knife in a sheath at her belt.

Image: Comet Hale-Bopp (NASA, JPL).