Those that I fight I do not hate,

Those that I guard I do not love.

— William Butler Yeats, An Irish Airman Foresees his Death

My mother used to joke about me, “Put a sheet with moving shadows in front of her and she will watch them.” Indeed, outside the lab I’m restless unless I’m reading books or watching films that engage me; both activities make me go instantly still for as long as the process lasts. My first encounter with le Carré was the film version of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold in the late sixties. Shot in stark black and white, with Richard Burton and a luminous Claire Bloom, it was that rare thing – an adaptation that honored its source.

So the day after I saw the film I marched into my extremely well-endowed high school library, searched the “Restricted” section (where all the interesting books were sequestered) and pounced. The librarian already knew me too well to object; I spirited my booty to safety and devoured it during my more boring classes, tucked inside textbooks. This was how I imprinted on le Carré. My appetite for him has remained unslaked down the decades. Among his (happy sigh!) still-lengthening output, my favorites are The Little Drummer Girl, The Constant Gardener and the two bookends of the Smiley trilogy.

Le Carré succeeds in what most authors dream of but few achieve: he creates fully realized worlds inhabited by complex human beings (well, men) dealing with complex issues. He manages this without resorting to infodumps or appendices. He is so self-assured that he commits several cardinal sins, according to the recipes of writing workshops: he always starts in media res, he never explains terms (Circus, mole, lamplighters, scalphunters, babysitters, wranglers, inquisitors) and he shifts viewpoints constantly and unapologetically. We get strobe glimpses of people and events from multiple angles. As these accumulate, they coalesce into a shimmering tesseract: the puzzle that inhabits the center of each story.

Le Carré’s books require attentive reading and are genuinely thought-provoking within their framework, whether this is Cold War rivalries, the Palestinian-Israeli conflict or big pharma shenanigans. To put it succinctly, they’re meant for mental and emotional adults. This defining attribute places them far above run-of-the-mill genre hackeries. It comes as no surprise that he was nominated for the Booker Prize. His characters highlight the often irreconcilable dilemmas of personal versus professional loyalties; in this he continues the work of Graham Greene, without Greene’s sanctimonious religiosity.

Much has been said about le Carré’s George Smiley being the antithesis to James Bond. Bond is the cardboard alpha male, festooned with glitzy gadgets and pneumatic trophy women. Smiley is one of the competent faceless geeks who uphold the world. In le Carré’s world of ambiguous morality and shadow games, Smiley hews to one lodestar: loyalty to “his people” – the people who become his chosen extended family by dint of putting flesh-and-blood humans above abstract principles or power plays. When he passes judgment on Bill Haydon in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy it is clear that in his eyes Haydon’s real betrayal was to choose status over people: the casual use and disposal of lovers and colleagues, not of the sorry parochial “principles” of the British Empire.

Smiley rarely wins: in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold he loses Alec Leamas and Liz Gold; in Tinker, Tailor he loses his home plus most of his clan. But when summoned to be a nettoyeur of Augean stables, he metes out justice like a Hollywood vigilante. Except he does it not with a gun but with information files; not with jazzy torture devices but with understanding of the fault lines that run through the hearts of men. Which brings us to the blind spot of Smiley and his creator. [Those of you who glaze over at the mere mention of women can skip the next three paragraphs and resume reading when I get back to issues deemed “universally” interesting.]

People will argue, correctly, that in showing the arrant sexism of mid-twentieth-century Britain le Carré was simply hewing to reality – as Prime Suspect did, decades later. After all, we speak of a culture that still manages to publish all-male “best of” anthologies and whose contemporary “literati” still publicly defend the use of cunt as an acceptable term of censure. However, le Carré’s women are not just abstractions on the page – they’re also abstractions to their own men. They fall into two overlapping categories: Bitch Goddesses and Distant Beacons, Arwens to pre-Andúril Aragorns. Bear in mind that le Carré is neither reactionary nor prudish: he included homosexuals without ostentatious ado even in his early works (Jim Prideaux, Connie Sachs) and Bill Haydon is a poster case of the Alkiviádhis-type lethal bisexual charmer. Yet his women fade into a pre-Raphaelite haze of watercolors and violin strings.

People will argue, correctly, that in showing the arrant sexism of mid-twentieth-century Britain le Carré was simply hewing to reality – as Prime Suspect did, decades later. After all, we speak of a culture that still manages to publish all-male “best of” anthologies and whose contemporary “literati” still publicly defend the use of cunt as an acceptable term of censure. However, le Carré’s women are not just abstractions on the page – they’re also abstractions to their own men. They fall into two overlapping categories: Bitch Goddesses and Distant Beacons, Arwens to pre-Andúril Aragorns. Bear in mind that le Carré is neither reactionary nor prudish: he included homosexuals without ostentatious ado even in his early works (Jim Prideaux, Connie Sachs) and Bill Haydon is a poster case of the Alkiviádhis-type lethal bisexual charmer. Yet his women fade into a pre-Raphaelite haze of watercolors and violin strings.

Ann Sercombe Smiley is both Bitch Goddess and Distant Beacon to everyone within her radius. Yet all we learn of her is that she is nobly born, radiantly beautiful and joylessly promiscuous (heaven forfend that even a heavenly “slut” should enjoy her urges). Most le Carré women are solely there to spur the men into action: the prototype is the tragic Irina, who’s summarily dispatched after she awakens Ricky Tarr’s slumbering conscience in Tinker, Tailor. Similar fates befall Liz Gold, a maiden/mother helpmate in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold; Katya Orlovna, almost entirely a parade of creaky pseudo-delphic utterances, in The Russia House (at least she may get ransomed); and Sophie Maplethorpe in The Night Manager. Louisa Pendel is there essentially as a bromance conduit in The Tailor of Panama. And Tessa Quayle, the ostensible moral center of The Constant Gardener, is safely dead and pedestalized before the novel even starts.

The exceptions are telling as well: Connie Sachs, the formidable intelligence analyst in the Smiley novels, is that universally derided stereotype, the bluestocking fag hag (“All my lovely boys!”). Her lesbianism, inexplicably elided in the recent film version of Tinker, Tailor, is shown as the constricting “loving jailor” Yourcenar/Frick variety. Charlie No-Last-Name of The Little Drummer Girl is an actress who is literally an empty vessel to be filled in by the men around her. Interestingly she was played by Diane Keaton, another male muse who was essentially a collection of tics, although the role was meant for Vanessa Redgrave, who knows full well what it means to be a strong woman embedded in dynasties of male-only “begats”.

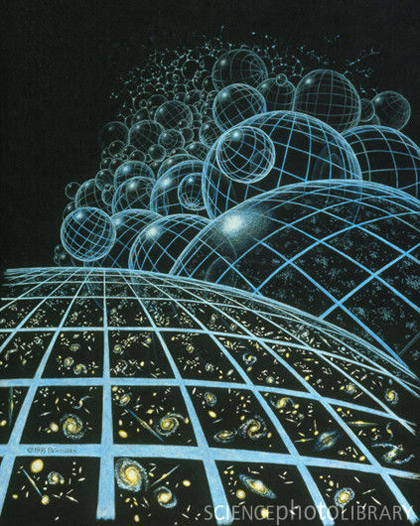

Le Carré’s two depictions of quasi-real women occur in Smiley’s People – possibly because they are the baits he uses to reel in his Soviet doppelgänger and nemesis, Karla, and hence they must demonstrate they deserve their glory-by-association. One of them, Maria Andreyevna Ostrakova (the always peerless Eileen Atkins), even breaks the mould of La Belle Dame sans Merci: she is almost elderly, unglamorous… and ferociously alive, attaining the stature of le Carré’s other fully realized humans. The other, Alexandra/Tatiana, is a tortured cipher who nevertheless shows glimpses of a specific person/ality buried in the cliché.

Alexandra is Karla’s daughter by a lover he adored but killed because he considered her a danger to the purity of his goal. Smiley uses this chink of humanity in Karla to break him. It is characteristic that he sunders all of his own human ties before this undertaking, so that he has no Achilles heel that jeopardizes his final task. In the end, Smiley reverses roles with Karla. By defecting to protect his daughter, Karla becomes flesh; by using Karla’s daughter to defeat him, Smiley turns to stone. Le Carré himself, moving from early Smiley to late Karla, maintains his stance of ambiguity up to his middle-late works. However, after the Cold War novels, his moral judgments become more absolute as his novels move out of the cloistered enclaves of MI6 and into the larger world where boardroom power games translate to millions of deaths and stunted lives.

Inevitably, many of le Carré’s works have been adapted to the screen. Given their complexity and the artificial demand that they be fitted to two-hour slots, they are mostly shadows of themselves. Beyond The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, the partial exceptions correspond to three of my four favorites. Le Carré agrees with my assessment, because he makes cameo appearances in two of them: The Little Drummer Girl and Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy.

The Little Drummer Girl retains a fair amount of le Carré’s Chinese puzzle structure and draws riveting performances from Klaus Kinski (a fiery Martin Kurtz) and Sami Frey (a spellbinding Khalil). However, the film is doomed by the total miscasting of Charlie (Diane Keaton, as discussed earlier) and Gadi/Joseph (Yórghos Voyagís) who drain their pivotal characters of both charisma and erotic chemistry. The Constant Gardener flattens most of the plot and character intricacies but boasts Ralph Fiennes as Justin Quayle (Ok, you can take away the smelling salts now…) and Rachel Weisz (Tessa Quayle) who can convey intense intelligence despite her beauty, as witnessed in her depiction of Hypatia in Agora.

And so we come to the jewel in the crown – Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy. The film has enormous shoes to fill: it must measure up not only to the book but also to the BBC series that also includes the other bookend, Smiley’s People. I watched it several times, once in a marathon session of fifteen hours spanning a new year transition. A TV series has the room to do justice to plot complexities and to showcase the ensemble acting of enormously talented professionals that has been a traditional glory of the British. Indeed, many people consider the BBC diptych the definitive version of the works. Its atmospherics are impeccable, exemplified by the increasingly frowning matryoshkas and a haunting rendition of Nunc dimittis in the credits. The characters are brought to electrifying life by the illustrious likes of Ian Richardson (Bill Haydon), Ian Bannen (Jim Prideaux), Alexander Knox (Control) and with Alec Guinness as the calm but formidable eye of the storm. The series unquestionably deserves all the accolades it gathered.

And so we come to the jewel in the crown – Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy. The film has enormous shoes to fill: it must measure up not only to the book but also to the BBC series that also includes the other bookend, Smiley’s People. I watched it several times, once in a marathon session of fifteen hours spanning a new year transition. A TV series has the room to do justice to plot complexities and to showcase the ensemble acting of enormously talented professionals that has been a traditional glory of the British. Indeed, many people consider the BBC diptych the definitive version of the works. Its atmospherics are impeccable, exemplified by the increasingly frowning matryoshkas and a haunting rendition of Nunc dimittis in the credits. The characters are brought to electrifying life by the illustrious likes of Ian Richardson (Bill Haydon), Ian Bannen (Jim Prideaux), Alexander Knox (Control) and with Alec Guinness as the calm but formidable eye of the storm. The series unquestionably deserves all the accolades it gathered.

Tomas Alfredson’s film also boasts impeccable period atmosphere (a feat, considering the distance from the time the book was written as well as the era it depicts) and once again the ensemble acting of high-octane professionals. Standouts: Mark Strong (Jim Prideaux), breaking his usual typecasting, speaks volumes with his eyes; Tom Hardy (Ricky Tarr) is as feral as the young Brando; John Hurt (Control) pulses with obsession and choler, wreathed in whisky fumes and cigarette smoke; and Benedict Cumberbatch (Peter Guillam), here shown as a closeted homosexual rather than a lady-killer, is a reluctant but conscientious convert to Smiley’s philosophy.

Gary Oldman, one of the few blonds in my personal gallery of talented eye candy, gives us a restrained, nuanced George Smiley. We cannot help but extrapolate to the turbulent waters underneath, if only from his previous portrayals of such tortured souls as Sid Vicious, Count Dracula and Sirius Black. Also, the fact that he’s a decade younger than Guinness when he portrayed Smiley makes the sudden yawning emptiness in his life far more palpable and poignant. Not surprisingly, there is incredible plot compression but the film never condescends to its audience: like the book, it demands focus and attention. There are countless small touches that convey enormous amounts of information – glances exchanged across tables, the lowering of a car window to let a bee fly out, a hand tightening on a banister.

Several items have been changed, some in the service of streamlining, others clearly aesthetic choices on the director’s part. I found two objectionable: Ann Smiley, whose face is never shown, is nevertheless implied to be far younger and more vulgar than her rarefied book persona (maintained in the series by the otherworldly Siân Phillips). Also, Jim Prideaux kills Bill Haydon with a long-distance rifle instead of snapping his neck, although in both cases Haydon is shown as aware and accepting of what is about to happen. This diminishes the emotional weight of the action, particularly on Prideaux’s side of the equation.

These caveats aside, the film version of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy is a worthy incarnation of the book, different enough from the TV series to be appreciated in its own right. Like Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, it is an unexpected gift. And gods and demons know how rare such gifts are, especially for someone like me who will still watch moving shadows on a sheet, but would rather watch truly original retellings of old myths.

Images: 1st, Shadow Theater Tales, Alexander Ovchinnikov; 2nd, Eileen Atkins as Maria Ostrakova in Smiley’s People; 3rd, the final matryoshka in the Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy BBC series credits; 4th, husked grains in Tinker, Tailor: Jim Prideaux (Mark Strong), Ricky Tarr (Tom Hardy), Peter Guillam (Benedict Cumberbatch).

Opening questions are how a story starts the seduction of our minds. To keep us reading, a story must carry out a balancing act, like a good joke, between logic and surprise.

Opening questions are how a story starts the seduction of our minds. To keep us reading, a story must carry out a balancing act, like a good joke, between logic and surprise. For further reading: Samuel R. Delany, “About 5,750 Words,” which can be found in his book, The Jewel-hinged Jaw: Notes on the Language of Science Fiction (Dragon Press, 1977; revised 2009). An excellent essay on how we read, and especially how we read science fiction.

For further reading: Samuel R. Delany, “About 5,750 Words,” which can be found in his book, The Jewel-hinged Jaw: Notes on the Language of Science Fiction (Dragon Press, 1977; revised 2009). An excellent essay on how we read, and especially how we read science fiction.