Note: This 2-part article is an expanded version of the talk I gave at Readercon 2011.

I originally planned to discuss how writers of SF need to balance knowledge of the scientific process, as well as some concrete knowledge of science, with writing engaging plots and vivid characters. But the more I thought about it, the more I realized that this discussion runs a parallel course with another; namely, depiction of non-Anglo cultures in Anglophone SF/F.

Though the two topics appear totally disparate, science in SF and non-Anglo cultures in SF/F often share the core characteristic of safe exoticism; that is, something which passes as daring but in fact reinforces common stereotypes and/or is chosen so as to avoid discomfort or deeper examination. A perfect example of both paradigms operating in the same frame and undergoing mutual reinforcement is Frank Herbert’s Dune. This is why we get sciency or outright lousy science in SF and why Russians, Brazilians, Thais, Indians and Turks written by armchair internationalists are digestible for Anglophone readers whereas stories by real “natives” get routinely rejected as too alien. This is also why farang films that attain popularity in the US are instantly remade by Hollywood in tapioca versions of the originals.

Before I go further, let me make a few things clear. I am staunchly against the worn workshop dictum of “Write only what you know.” I think it is inevitable for cultures (and I use that term loosely and broadly) to cross-interact, cross-pollinate, cross-fertilize. I myself have seesawed between two very different cultures all my adult life. I enjoy depictions of cultures and characters that are truly outside the box, emphasis on truly. At the same time, I guarantee you that if I wrote a story embedded in New Orleans of any era and published it under my own culturally very identifiable name, its reception would be problematic. Ditto if I wrote a story using real cutting-edge biology.

These caveats do not apply to secondary worlds, which give writers more leeway. Such work is judged by how original and three-dimensional it is. So if a writer succeeds in making thinly disguised historical material duller than it was in reality, that’s a problem. That’s one reason why Jacqueline Carey’s Renaissance Minoan Crete enthralled me, whereas Guy Gavriel Kay’s Byzantium annoyed me. I will also leave aside stories in which science is essentially cool-gizmos window dressing. However, use of a particular culture is in itself a framing device and science is rarely there solely for the magical outs it gives the author: it’s often used to promote a world view. And when we have active politics against evolution and in favor of several kinds of essentialism, this is something we must keep not too far back in our mind.

So let me riff on science first. I’ll restrict myself to biology, since I don’t think that knowledge of one scientific domain automatically confers knowledge in all the rest. Here are a few hoary chestnuts that are still in routine use (the list is by no means exhaustive):

— Genes determining high-order behavior, so that you can instill virtue or Mozartian composing ability with simple, neat, trouble-free cut-n-pastes (ETA: this trope includes clones, who are rarely shown to be influenced by their many unique contexts). It runs parallel with optimizing for a function, which usually breaks down to women bred for sex and men bred for slaughter. However, evolution being what it is, all organisms are jury-rigged and all optimizations of this sort result in instant dead-ending. Octavia Butler tackled this well in The Evening and the Morning and the Night.

— The reductionist, incorrect concept of selfish genes. This is often coupled with the “women are from Venus, men are from Mars” evo-psycho nonsense, with concepts like “alpha male rape genes” and “female wired-for-coyness brains”. Not surprisingly, these play well with the libertarian cyberpunk contingent as well as the Vi*agra-powered epic fantasy cohort.

— Lamarckian evolution, aka instant effortless morphing, which includes acquiring stigmata from VR; this of course is endemic in film and TV SF, with X-Men and The Matrix leading the pack – though Star Trek was equally guilty.

— Its cousin, fast speciation (Greg Bear’s cringeworthy Darwin’s Radio springs to mind; two decent portrayals, despite their age, are Poul Anderson’s The Man Who Counts and The Winter of the World). Next to this is rapid adaptation, though some SF standouts managed to finesse this (Joan Slonczewski’s A Door into Ocean, Donald Kingsbury’s Courtship Rite).

— The related domain of single-note, un-integrated ecosystems (what I call “pulling a Cameron”). As I mentioned before, Dune is a perfect exemplar though it’s one of too many; an interesting if flawed one is Mary Doria Russell’s The Sparrow. Not surprisingly, those that portray enclosed human-generated systems come closest to successful complexity (Morgan Locke’s Up Against It, Alex Jablokov’s River of Dust).

— Quantum consciousness and quantum entanglement past the particle scale. The former, Roger Penrose’s support notwithstanding, is too silly to enlarge upon, though I have to give Elizabeth Bear props for creative chuzpah in Undertow.

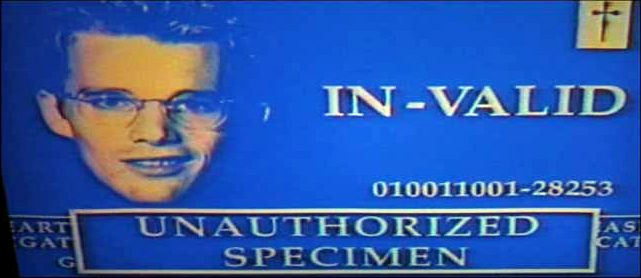

— Immortality by uploading, which might as well be called by its real name: soul and/or design-by-god – as Battlestar Galumphica at least had the courage to do. As I discussed elsewhere, this is dualism of the hoariest sort and boring in the bargain.

— Uplifted animals and intelligent robots/AIs that are not only functional but also think/feel/act like humans. This paradigm, perhaps forgivable given our need for companionship, was once again brought to the forefront by the Planet of the Apes reboot, but rogue id stand-ins have run rampant across the SF landscape ever since it came into existence.

These concepts are as wrong as the geocentric universe, but the core problems lie elsewhere. For one, SF is way behind the curve on much of biology, which means that stories could be far more interesting if they were au courant. Nanobots already exist; they’re called enzymes. Our genes are multi-cooperative networks that are “read” at several levels; our neurons, ditto. I have yet to encounter a single SF story that takes advantage of the plasticity (and potential for error) of alternative splicing or epigenetics, of the left/right brain hemisphere asymmetries, or of the different processing of languages acquired in different developmental windows.

For another, many of the concepts I listed are tailor-made for current versions of triumphalism and false hierarchies that are subtler than their Leaden Age predecessors but just as pernicious. For example, they advance the notion that bodies are passive, empty chassis which it is all right to abuse and mutilate and in which it’s possible to custom-drop brains (Richard Morgan’s otherwise interesting Takeshi Kovacs trilogy is a prime example). Perhaps taking their cue from real-life US phenomena (the Teabaggers, the IMF and its minions, Peter Thiel…) many contemporary SF stories take place in neo-feudal, atomized universes run amuck, in which there seems to be no common weal: no neighborhoods, no schools, no people getting together to form a chamber music ensemble, play soccer in an alley, build a telescope. In their more benign manifestations, like Iain Banks’ Culture, they attempt to equalize disparities by positing infinite resources. But they hew to disproved paradigms and routinely conflate biological with social Darwinism, to the detriment of SF.

Mindsets informed by these holdovers won’t help us understand aliens of any kind or launch self-enclosed sustainable starships, let alone manage to stay humane and high-tech at the same time. Because, let’s face it: the long generation ships will get us past LEO. FTLs, wormholes, warp drives… none of these will carry us across the sea of stars. It will be the slow boats to Tau Ceti, like the Polynesian catamarans across the Pacific.

Mindsets informed by these holdovers won’t help us understand aliens of any kind or launch self-enclosed sustainable starships, let alone manage to stay humane and high-tech at the same time. Because, let’s face it: the long generation ships will get us past LEO. FTLs, wormholes, warp drives… none of these will carry us across the sea of stars. It will be the slow boats to Tau Ceti, like the Polynesian catamarans across the Pacific.

You may have noticed that many of the examples that I used as good science have additional out-of-the-box characteristics. Which brings us to safe exoticism on the humanist side.

Images: 1st, Bunsen and his hapless assistant, Beaker (The Muppet Show); 2nd, the distilled quintessence of safe exoticism: Yul Brynner in The King and I.

Related entries:

SF Goes McDonald’s: Less Taste, More Gristle

To the Hard Members of the Truthy SF Club

Miranda Wrongs: Reading too Much into the Genome

Ghost in the Shell: Why Our Brains Will Never Live in the Matrix