In 2010, the recipient for the Medicine Nobel was Robert Edwards, who perfected in vitro fertilization (IVF) techniques for human eggs in partnership with George Steptoe. Their efforts culminated with the conception of Louise Brown in 1978, followed by several million such births since. The choice was somewhat peculiar, because this was an important technical advance but not an increase in basic understanding (which also highlights the oddity of not having a Nobel in Biology). That said, the gap between the achievement and its recognition was unusually long. This has been true of others who defied some kind of orthodoxy – Barbara McClintock is a poster case.

In Edwards’ case, the orthodoxy barrier was conventional. Namely, IVF separates sex from procreation as decisively as contraception does. Whereas contraception allows sex without procreation (as do masturbation and most lovemaking permutations), IVF allows conception minus orgasms and also decouples ejaculation from fatherhood. Sure enough, a Vatican representative voiced his institution’s categorical disapproval for this particular bestowal. However, IVF has detractors even among the non-rabidly religious. The major reason is its residue: unused blastocysts, which are routinely discarded unless they’re used as a source for embryonic stem cells.

Around the same time that Edwards received the Nobel, US opponents of embryonic stem cell research filed a lawsuit contending that this “so far fruitless” research siphoned off funds from “productive” adult stem cell research. The judge in the case handed down a decision that amounted to a ban of all embryonic stem cell work and the case has been a legal and political football ever since. The brouhaha has highlighted two questions: what good are stem cells? And what is the standing of blastocysts?

Let me get the latter out of the way first. Since IVF blastocysts are eventually discarded if not used, most dilemmas associated with them reek with hypocrisy and the transparent desire to curtail women’s autonomy. A 5-day blastocyst consists of 200 cells arising from a zygote that has not yet implanted. If it implants, 50 of these eventually become the embryo; the rest turn into the placenta. A blastocyst is a potential human as much as an acorn is a potential oak – perhaps even less, given how much it needs to attain viability. Equally importantly, blastocysts don’t feel pain. For that you need to have a nervous system that can process sensory input. In humans, this happens roughly near the end of the second trimester – which is one reason why extremely premature babies have severe neurological defects.

This won’t change the mind of anyone who believes that a zygote is “ensouled” at conception, but if we continue along this axis (very similar to much punitive fundamentalist reasoning) we will end up declaring miscarriage a crime. This is precisely what several US state legislatures are currently attempting to do, with the “Protect Life Act” riding pillion, bringing us squarely into Handmaid’s Tale territory. It is well known by now that something like forty percent of all conceptions end in early miscarriages, many of them unnoticed or noticed only as heavier than usual monthly bleeding. A miscarriage almost invariably means there is something seriously wrong with the embryo or the embryo/placenta interaction. Forcing such pregnancies to continue would result in significant increase of deaths and permanent disabilities of both women and children.

The “instant ensoulment” stance is equivalent to the theories that postulated a fully formed homunculus inside each sperm and deemed women passive yet culpable vessels. It is also noteworthy that the concern of compulsory-pregnancy advocates stops at the moment of birth. Across eras, girls have been routinely killed at all ages by exposure, starvation, poisoning, beatings; boys suffered this fate only if they were badly deformed in cultures or castes that demanded physical perfection.

Let’s now focus on the scientific side. By definition, stem cells must have the capacity to propagate indefinitely in an undifferentiated state and the potential to become most cell types (pluripotent). Only embryonic stem cells (ESCs) have these attributes. Somatic adult stem cells (ASCs), usually derived from skin or bone marrow, are few, cannot divide indefinitely and can only differentiate into subtypes of their original cellular family (multipotent). In particular, it’s virtually impossible to turn them into neurons, a crucial requirement if we are to face the steadily growing specter of neurodegenerative diseases and brain or spinal cord damage from accidents and strokes.

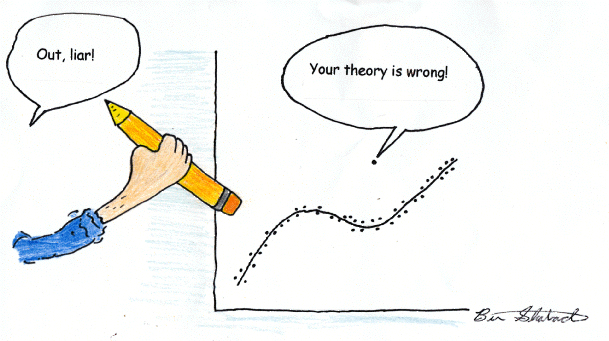

Biologists have discovered yet another way to create quasi-ESCs: reprogrammed adult cells, aka induced pluripotent cells (iPS). However, it comes as no surprise that iPS have recently been found to harbor far larger numbers of mutations than ESCs. To generate iPS, you need to jangle differentiated cells into de-differentiating and resuming division. The chemical path is brute-force – think chemotherapy for cells and you get an inkling. The alternative is to introduce an activated oncogene, usually via a viral vector. By definition, oncogenes promote cell division which raises the very real prospect of tumors. Too, viral vectors introduce a host of uncontrolled variables that have so far precluded fine control.

ESCs are not tampered with in this fashion, although long-term propagation can cause epi/genetic changes on its own. Additionally, recent advances have allowed researchers to dispense with mouse feeder cells for culturing ESCs. These carried the danger of transmitting undesirable entities, from inappropriate transcription factors to viruses. On the other hand, ASC grafts from one’s own tissues are less likely to be rejected (though xeno-ASCs are even likelier than ESCs to be tagged as foreign and destroyed by the recipient’s immune system).

Studies of all three kinds of stem cells have helped us decipher mechanisms of both development and disease. This research allowed us to discover how to enable cells to remain undifferentiated and how to coax them toward a desired differentiation path. Stem cells can also be used to test drugs (human lines are better indicators of outcomes than mice) and eventually generate tissue for cell-based therapies of birth defects, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Huntington’s, ALS, spinal cord injury, stroke, diabetes, heart disease, cancer, burns, arthritis… the list is long. Cell-based therapies have advantages over “naked” gene delivery, because genes delivered in cells retain the regulatory signals and larger epi/genetic contexts crucial for long-term survival, integration and function.

People argue that ASCs (particularly hematopoetic precursors used in bone marrow transplants) have been far more useful than ESCs, whose use is still potential. However, they usually fail to note that ASCs have been in clinical use since the late fifties, whereas human ESCs were first isolated in 1998 by James Thomson’s group in Wisconsin. Add to that the various politically or religiously motivated embargoes, and it’s a wonder that our understanding of ESCs has advanced as much as it has.

Despite fulminations to the contrary, women never make reproductive decisions lightly since their repercussions are irreversible, life-long and often determine their fate. Becoming a human is a process that is incomplete even at birth, since most brain wiring happens postnatally. Demagoguery may be useful to lawyers, politicians and control-obsessed fanatics. But in the end, two things are true: actual humans are (should be) much more important than potential ones – and this includes women, not just the children they bear and rear; and embryonic stem cells, because of their unique properties, may be the only path to alleviating enormous amounts of suffering for actual humans.

Best FAQ source: NIH stem cell page